of 2 214 species assessed are

Threatened

of 2 214 species assessed are

Rare or Critically Rare

species of spiders (58%) are

Endemic

Key findings

South Africa has a rich diversity of spider species, with 2 265 described species1, representing 4% of the world’s spiders.

A comprehensive assessment of 2 214 spider species was conducted for the first time between 2016 and 2019 using the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Categories and Criteria. This assessment is a global first and a pioneering effort in applying IUCN Red List criteria to a mega-diverse invertebrate group2.

The spider assessment was made possible through the 22-year South African National Survey of Arachnida (SANSA) initiative, which resulted in significant improvements to the knowledge base: a 33% increase in described species and, during this project, a 350% rise in specimen accessions in the national collection.

Of the assessed species, only 78 of the species (4%) were assessed as threatened.

Most species (1 419 species, 64%) are widely distributed with no known threats and are assessed as Least Concern.

Importantly, almost a third of the species (707 species, 32%) are assessed as Data Deficient, meaning that a large number of species need further research before their risk of extinction can be determined.

Endemism is high, with 1 303 species (58%) found only in South Africa, representing around 2% of the world’s spiders.

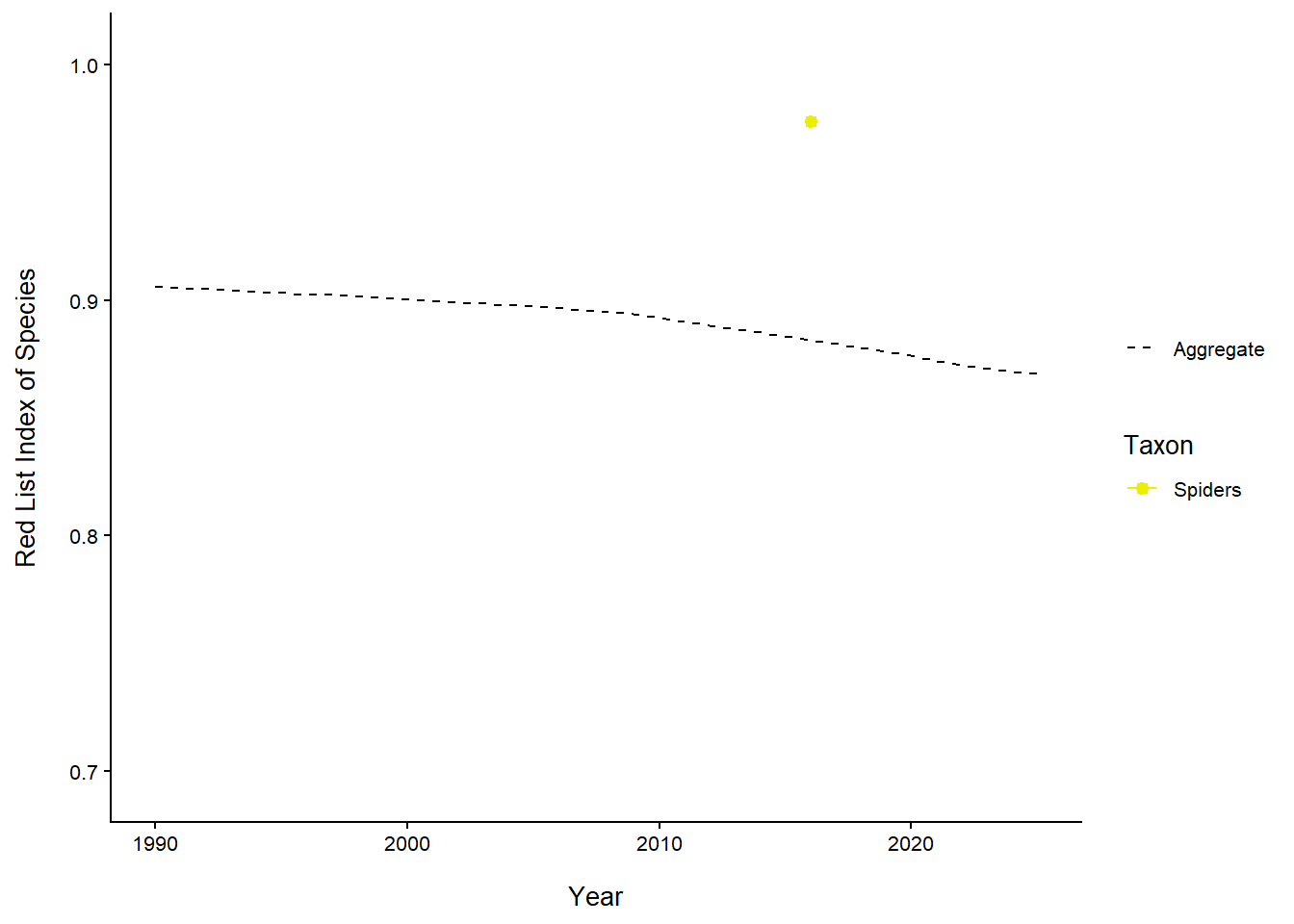

In the IUCN Red List Index (RLI) assessment, spiders currently have the highest RLI score of all South African taxonomic groups, making them appear the least threatened. However, many species remain unevaluated due to limited information. As a result, their true status is uncertain – more species may prove to be threatened, or many may be Least Concern. This uncertainty means the current RLI value should be interpreted with caution.

The major threats to spiders are habitat loss due to fire, overgrazing, invasive plants, mining, agricultural practices, and urban development.

Threat status

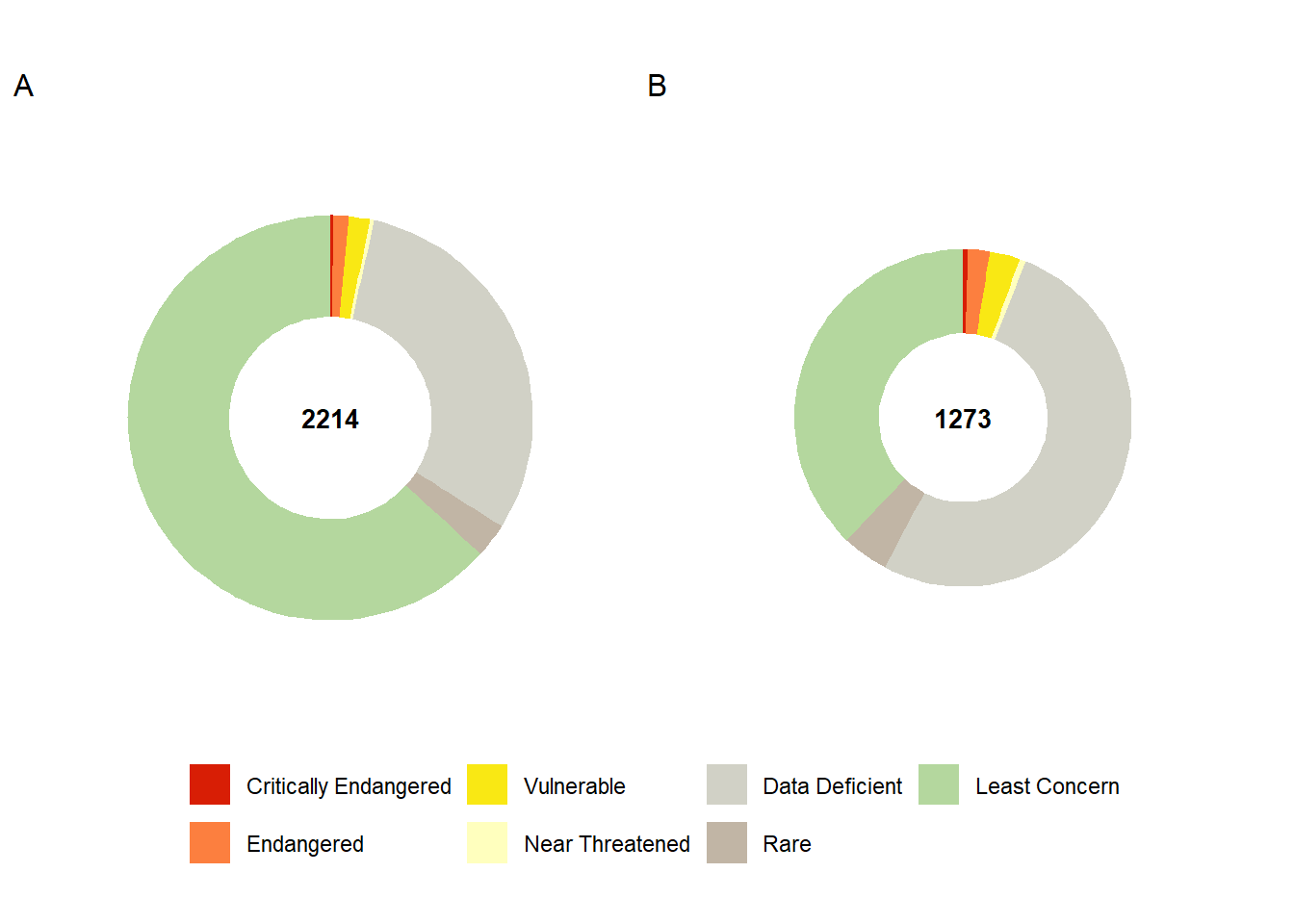

In 2016, South Africa assessed 2 214 indigenous spider species for the first time using the IUCN Red List categories and criteria, which measure extinction risk2. Of the assessed species, 78 (4%) were threatened with extinction: 23 are Critically Endangered (CR), 24 are Endangered (EN), and 31 are Vulnerable (VU). No species were found to be extinct or possibly extinct.

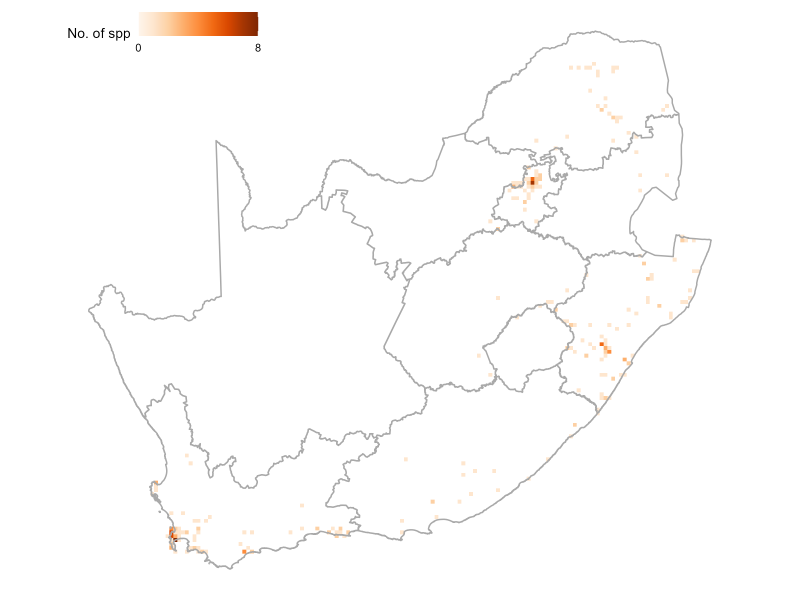

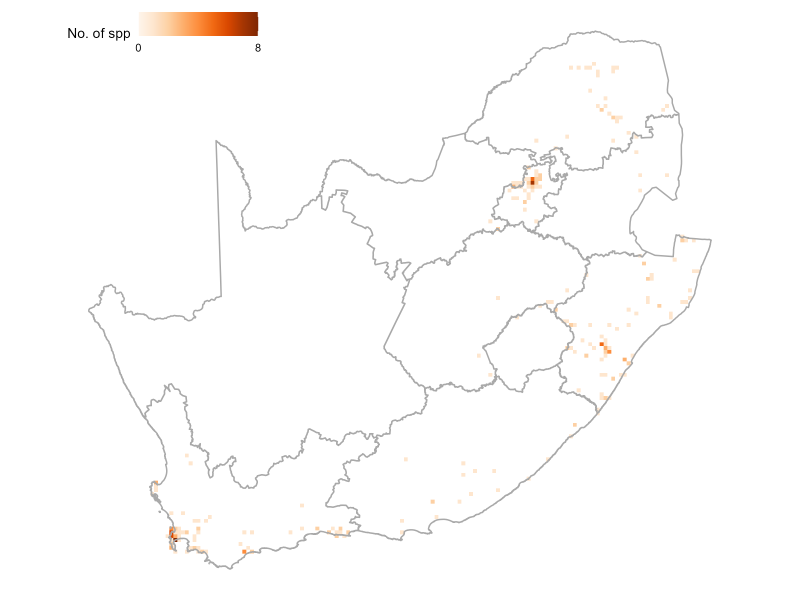

Highly threatened spiders occur in the three major urban centres of South Africa (Western Cape, Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal). This could be an indication of sample bias, but also identifies areas that have lost large areas of habitat to urban expansion (Figure 1). Some species have very restricted ranges yet face no anthropogenic threats. These are listed under South Africa’s national rarity categories: Rare (extent of occurrence <500 km²) or Critically Rare (known from a single location). Sixteen spider species were classified as Critically Rare and 44 species as Rare. Although such species are assessed as Least Concern under the IUCN system, they remain a priority for national conservation and are included as taxa of conservation concern along with threatened, Near Threatened and Data Deficient species.

Most species (1 419, 63%) are widespread, face no known threats, and are assessed as Least Concern (Figure 2). A large proportion (675, 30%) are Data Deficient, highlighting the need for more research, particularly providing more detailed taxonomic descriptions, describing unknown sexes and providing additional distribution data through field sampling and examination of museum material (see Box 1).

Endemism is high, with 1 325 species (59%) found only in South Africa, representing 2% of global spider diversity. Of the 72 spider families recorded, Salticidae (jumping spiders) is the most species-rich (354), followed by Gnaphosidae (195) and Thomisidae (143)1. Because of its size, Salticidae also has the highest number of threatened (6) and Data Deficient (98) species.

However, the greatest conservation concern lies with smaller, cryptic species in isolated habitats such as caves and fragmented habitats. Families such as Pholcidae, Archaeidae, and Corinnidae each include four threatened species. Families with the highest numbers of Rare or Critically Rare species are Pholcidae (18), Salticidae (5) and Drymusidae (4)2.

| Taxon | Critically Endangered | Endangered | Vulnerable | Near Threatened | Data Deficient | Rare | Least Concern | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall spiders | 6 | 26 | 37 | 8 | 675 | 60 | 1402 | 2214 |

| Endemic spiders | 6 | 26 | 37 | 8 | 657 | 57 | 482 | 1273 |

Trends – the Red List Index

The trend in spider extinction risk was measured using a global standard indicator, the IUCN Red List Index (RLI) of species5. The RLI is calculated for each taxonomic group based on genuine changes in Red List categories over time. The RLI value ranges from 0 to 1. At a value of 1, all species are at low risk of extinction (Least Concern), while a value of 0 indicates that all species are extinct. The RLI value for spiders in South Africa was calculated in 2020 and included 2 214 species. The RLI value is 0.994, and relative to other taxon groups assessed in South Africa, spiders have the highest RLI value (Figure 3). Since only one assessment has been conducted for spiders, it is not possible to determine the trend in extinction risk for this group. It is important to note that many Data Deficient species are included in the assessment, and hence there is still a high level of uncertainty associated with this result.

Pressures

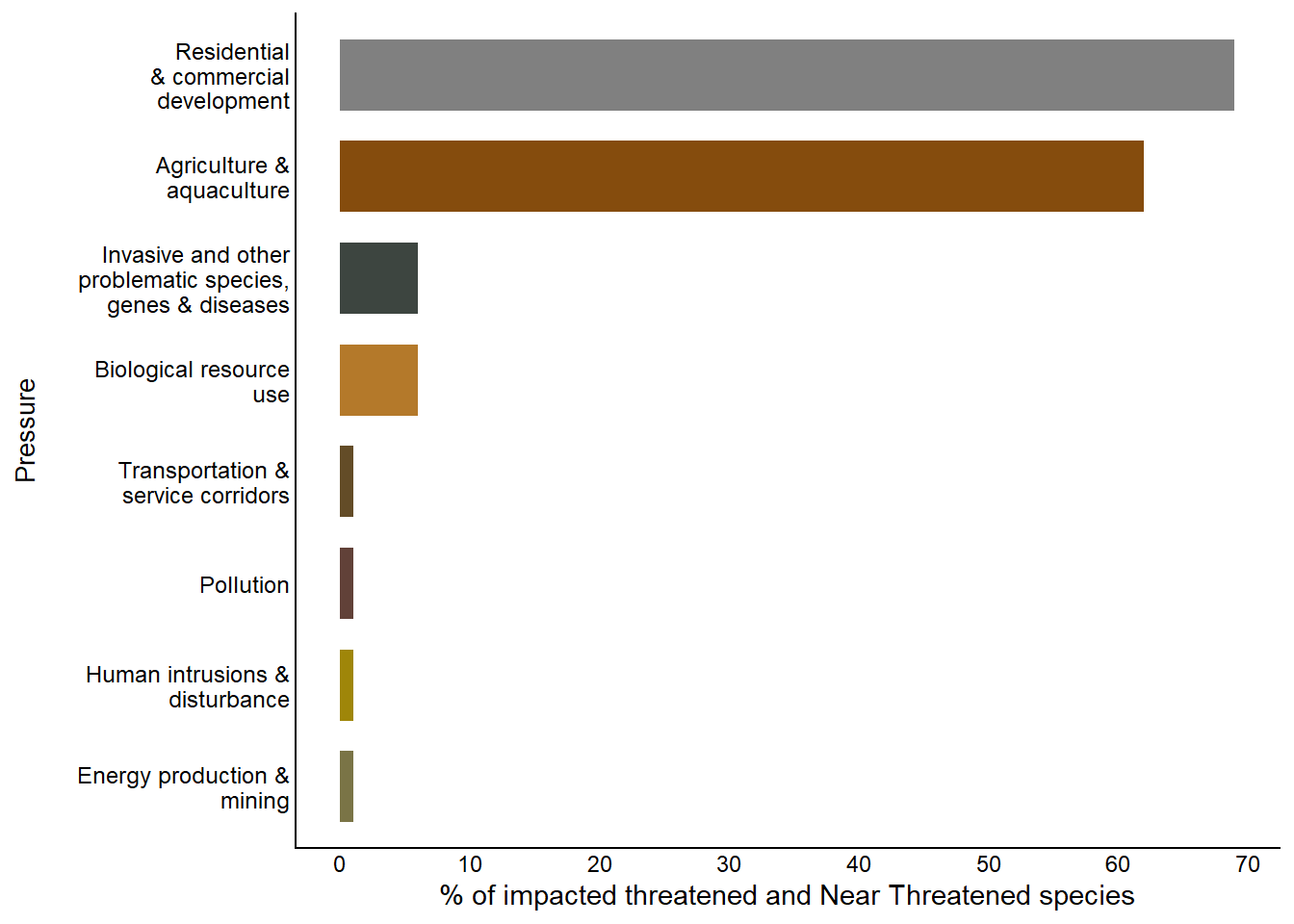

Spiders face an array of threats – both natural and human-driven (Figure 4). Research has shown that habitat loss caused by fire (see Box 2), overgrazing and invasive alien species infestations have a direct impact on spider populations, causing local losses3. Urban expansion, agriculture, forestry, and mining are the leading causes of habitat loss for spiders. These pressures are especially important for ground-dwelling and endemic species with poor dispersal abilities. In South Africa, many spider species are highly localised and endemic to specific biomes, such as fynbos6 with 28% endemic species to this biome, and savanna7 with 30% of the species endemic. Ground-dwelling spiders are particularly vulnerable to changes in their habitat and often struggle to recolonise areas after disturbance due to their limited dispersal capabilities, making them more prone to local extinction.

Spiders are present in relatively high numbers in agro-ecosystems. However, it has been shown that they are negatively impacted by pesticide use8. Thus far, 51 families from 413 species have been recorded from crops in South Africa, and five agrobiont species have been identified that play an important role as natural control agents of agricultural pests. However, chemical use can directly kill spiders or disrupt their prey base. Integrated pest management (IPM) and organic farming are recommended to reduce chemical exposure that harms spiders and their prey. Altered temperature and rainfall patterns (likely from climate change) can affect spider distribution, reproduction, and prey availability, and they may be severely impacted by drought.

Some spiders are threatened due to poaching and are used as pets such as the species in the Theraphosidae family (baboon spiders). Baboon spiders are ecologically significant predators within South African ecosystems, contributing to the population regulation of a variety of insect species9. Tthreats from illegal collection for the exotic pet trade are increasing, driven by their popularity among arachnid enthusiasts. Depleted wild populations can take a long time to recover, due to the species’ long lifespans and low reproductive rates4,9. Although national legislation provides protection for baboon spiders, enforcement remains inconsistent, and improved regulatory measures are needed to prevent unsustainable collecting from the wild9.

Knowledge gaps

A significant portion of the South African spider fauna remains undescribed. In the Cape Floristic Region, 24% of species are classified as Data Deficient, and two families (Synotaxidae and Theridiosomatidae) are only known from undescribed species. Studies on mygalomorph trapdoor spiders (e.g. Stasimopus, Ancylotrypa, Galeosoma) show taxonomic resolution as low as 15–29%, indicating high uncertainty in species delimitation.

Sampling bias and geographic gaps are a concern. Spider records are heavily concentrated in the eastern and coastal regions of South Africa, with North West, Northern Cape and Mpumalanga province remaining undersampled1,2,14. These sampling biases impede conservation assessments and ecological modelling. Making use of citizen science to contribute to observations, both helps fill sampling gaps and also raises awareness (see Box 3).

Morphological variation is poorly understood due to limited sampling, making it difficult to confidently define species boundaries. Despite SANSA’s efforts, many natural history collections lack comprehensive coverage or standardised metadata, limiting their utility for taxonomic synthesis. Large numbers of specimens in collections remain unidentified due to a lack of spider taxonomists. For example, a recent meta-analysis of South African spider data from seven collections found that only slightly more than half of around 121 000 records had been identified to species level, indicating a major taxonomic gap in the available data14. Presently, there is only one spider taxonomist employed at a natural history collection. The shortage of taxonomic expertise will have direct consequences for resolving Data Deficient taxa and developing taxonomic products related to species descriptions, revisions, and the integration of molecular tools.

Addressing the taxonomic impediment for spiders in South Africa requires a multi-pronged strategy that blends capacity building, infrastructure development, and policy integration. The following is a breakdown of suggested solutions:

Expansion of taxonomic capacity by creating employment for specialist taxonomists and providing the required skills transfer opportunities (see Box 4).

Accelerate species descriptions through capacity building and collaborative research, particularly with international partners.

Integrate molecular tools and promote DNA barcoding and phylogenetics to resolve species boundaries, especially in morphologically conservative groups.

Develop a national spider barcode reference library linked to voucher specimens and ecological metadata. Currently, sequence data on South African spiders (around 10 600 specimens processed, mainly COI-5P) is scattered among several projects with strongly contrasting levels of taxonomic resolution.

Digitize and standardise collections with high-resolution imaging, georeferencing, and standardised metadata.

Support the evolution of natural science collection databases to be more accessible by improving the use of centralized database accessible to researchers, conservationists, and policy-makers.

Encourage citizen science platforms like iNaturalist to crowdsource observations and expand distribution data (see Box 3).

Relax permit conditions so that members of the public can sample specimens without fear of prosecution, particularly those linked to photographic observations, to enable species-level identifications.

Link taxonomic work to spatial tools for species conservation, e.g. Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) and the DFFE’s Environmental Screening Tool for Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), to justify funding and urgency. This can be further linked to understanding biodiversity data and the role it could play in South Africa’s biosecurity with regards to emerging pests and diseases.

Foster international collaboration and partner with global arachnological networks for training, data sharing, and joint revisions.

Invite and fund visiting taxonomists to work on South African material and co-author species descriptions.

Facilitate the training of taxonomists from other African countries to expand the skills base on the continent.

Approach

Threat status assessments

The first IUCN Red List assessment of South African spiders was conducted between 2016 and 2019, as a collaborative project between the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI), the Agricultural Research Council, the University of the Free State and the University of Venda (formerly University of Limpopo). This assessment represents a pioneering effort in applying IUCN Red List criteria to a mega-diverse invertebrate group. It was made possible through the 22-year South African National Survey of Arachnida (SANSA) initiative, which resulted in significant improvements to the knowledge base: a 33% increase in described species and a 350% rise in specimen accessions in the ARC’s National Collection of Arachnida (NCA). See details about how the IUCN Red List assessments are conducted here

Data sources and methods

The assessment utilised data from the First Atlas of South African Spiders4, which compiled information from two primary sources: the National Collection of Arachnida (NCA) at the Agricultural Research Council – Plant Health and Protection (ARC-PHP) in Roodeplaat, Pretoria (with over 60 000 records) and published taxonomic literature from 17 museum collections.

The distribution of occurrence records across South Africa, Lesotho and Eswatini was visualised using quarter-degree, degree-square and density kernel plots for all 76 069 records. However, records in the NCA that were not identified to species level were excluded from the Red List assessments, reducing the analytical dataset to 23 827 species-level records covering 2 253 known South African spider species.

Calculation of parameters

The calculation of Red List parameters was performed using the R package red (v1.6.3)15. Spatial analyses on observed occurrences used functions for calculating Extent of Occurrence (EOO), Area of Occupancy (AOO), and elevational range. EOO was calculated as the minimum convex polygon around all occurrences, while AOO was determined by the number of 2 km² cells occupied. When EOOs were smaller than the AOO, they were made equal. Assessments were drafted as per the IUCN documentation standards and reviewed by relevant experts.

Assessment criteria and limitations

All Red List assessments relied exclusively on IUCN criteria B (geographic range) or D (population size), as these could be evaluated from available distribution data and inferred threats. The other IUCN criteria (A, C, and E) require empirical evidence of population dynamics and trends – a critical data gap known as the Prestonian shortfall – which remains unavailable for most spider species. This methodological constraint highlights the need for long-term monitoring programs to provide insights into population dynamics.

Acknowledgements

The first IUCN Red List assessment of South African spiders was conducted between 2016 and 2019, as a collaborative project between the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI), the Agricultural Research Council (ARC), the University of the Free State, National Museum Bloemfontein, and the University of Venda (formerly University of Limpopo), with the National Research Foundation (NRF) providing funding and support. South African National Parks and E. Oppenheimer & Son support and provide opportunities to collect in the parks and reserves and the provincial conservation agencies for collecting permits.

Coordinated by:

Contributors

| Contributor | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Annette van den Berg | Agricultural Research Council |

| Astri Leroy | Spider Club of Southern Africa |

| Colin Schoeman | University of Venda |

| Connie Anderson | Agricultural Research Council |

| Esethu Nkibi | South African National Biodiversity Institute |

| Eugene Modiseng | Agricultural Research Council |

| Keenan Meissenheimer | South African National Biodiversity Institute |

| Mohale Mokoena | South African National Biodiversity Institute |

| Norbert Hahn | University of Venda |

| Petro Marais | Agricultural Research Council |

| Reginald Christiaan | South African National Biodiversity Institute |

| Robin Lyle | Agricultural Research Council |

| Ruan Booysen | University of Free State |

| Sma Chiloane | Agricultural Research Council |

| Carol Poole | South African National Biodiversity Institute |

| Anisha Dayaram | South African National Biodiversity Institute |

Recommended citation

Dippenaar-Schoeman, A., Lyle, R., Raimondo, D.C., Sethusa, T., Foord, S., Haddad, C., Lotz, L., Hendricks, S.E., Monyeki, M.S., & Van Der Colff, D. 2025. Spiders. National Biodiversity Assessment 2025. South African National Biodiversity Institute. http://nba.sanbi.org.za/.