of 135 species assessed are

Threatened

of 133 assessed species are

Well Protected

of threatened amphibians are

Under-protected

Key findings

The latest amphibian assessment evaluated 135 species and 82 (61%) of these are endemic or near-endemic to South Africa, Eswatini, and Lesotho.

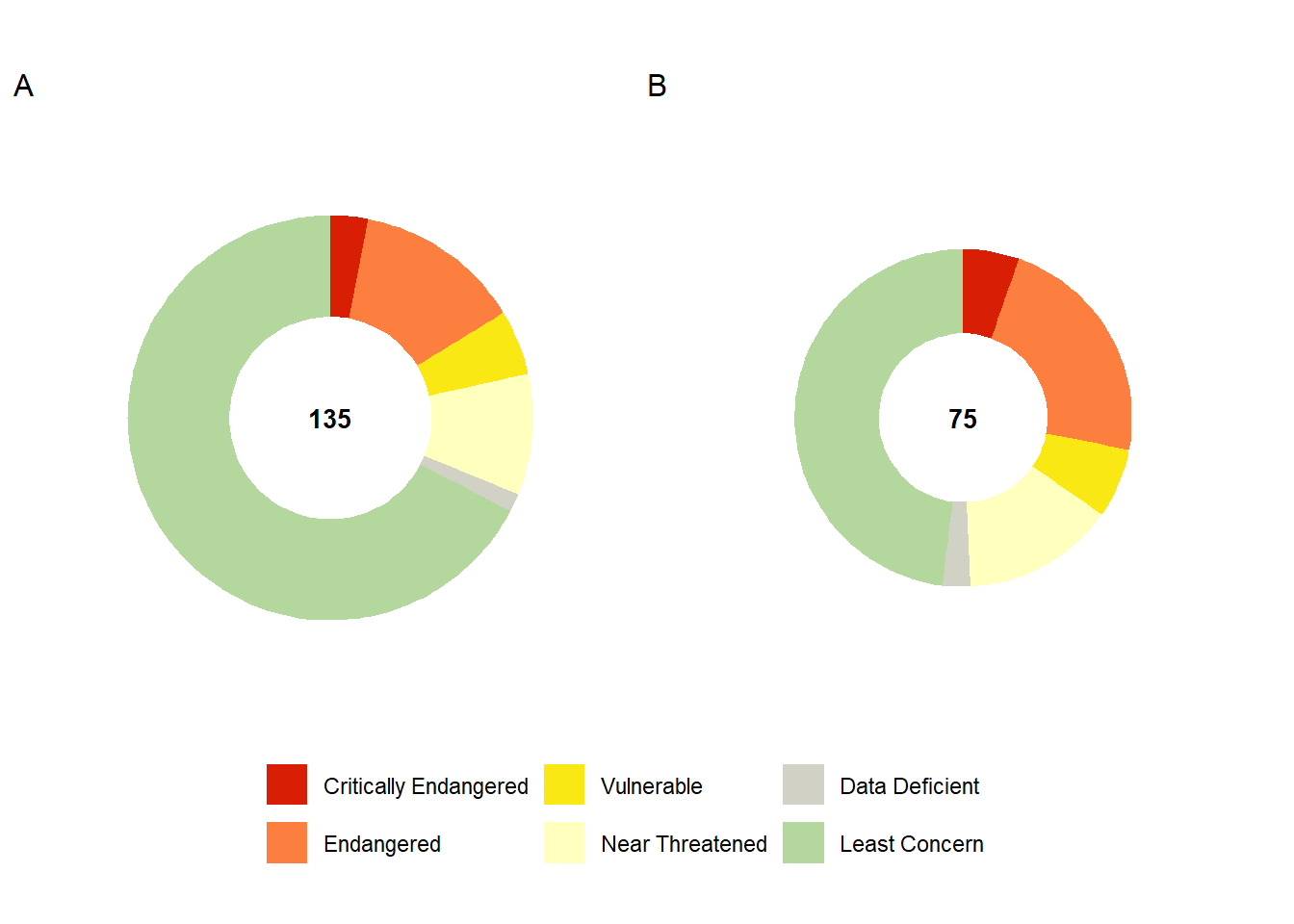

A total of 22% of assessed amphibians (30 species) are threatened with extinction, with another 10% (13) assessed as Near Threatened.

Among South Africa’s endemic amphibians, 39% are threatened with extinction, placing full responsibility for their protection on South Africa.

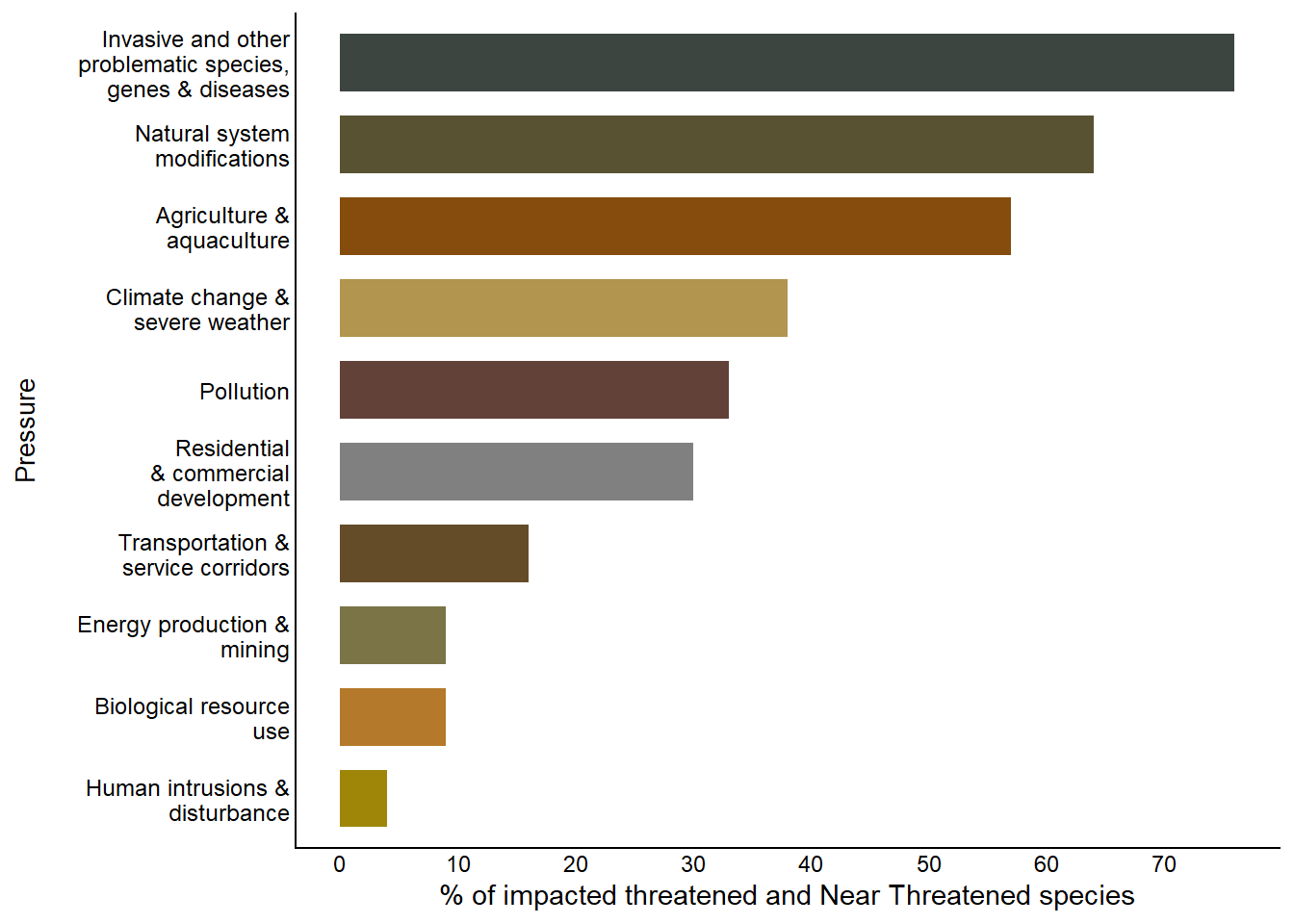

Amphibians in South Africa continue to decline mainly due to invasive and other problematic species, impacting 83% of threatened species. Impacts range from infectious diseases to drying out and replacement of habitat by invasive alien plants. This is followed by habitat loss and degradation due to agriculture (72%), and natural system modification (69%) related to, for example, wetland drainage, overgrazing, and inappropriate fire cycles.

Recognised as the most important emerging threat globally, climate change impacts are also becoming an important driver of amphibian declines in South Africa affecting nearly half of threatened species, although the impacts of this threat are challenging to quantify.

A large proportion of amphibians are assessed as Well Protected (73%) within the South African protected area network. Eleven percent (15) of amphibian species are Not Protected. Among the 29 threatened species, 79% are considered under-protected (Moderately Protected, Poorly Protected or Not Protected). The most threatened amphibians are therefore also most in need of improved protection, particularly improvement of protected area management to support amphibian persistence.

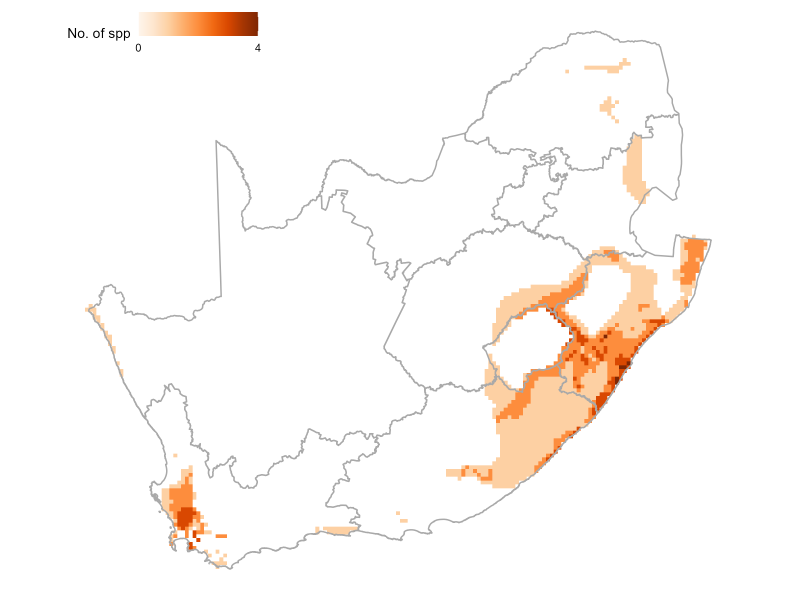

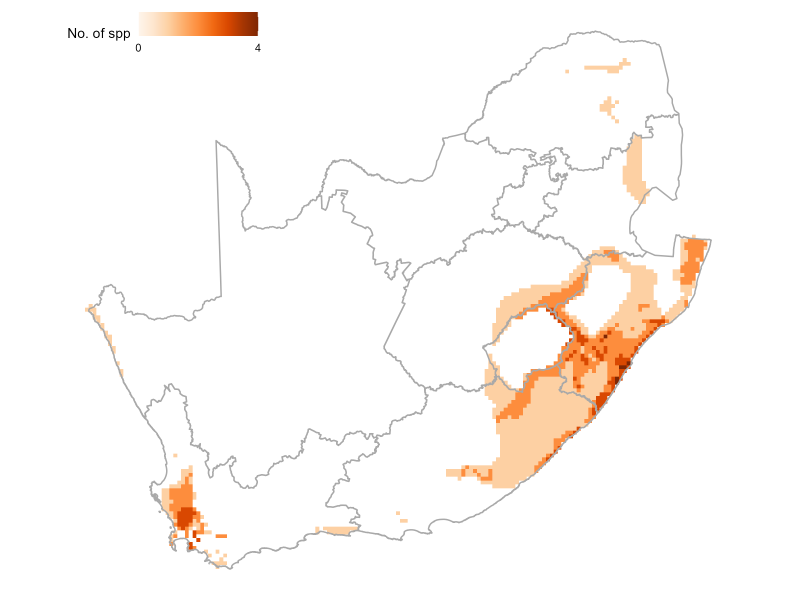

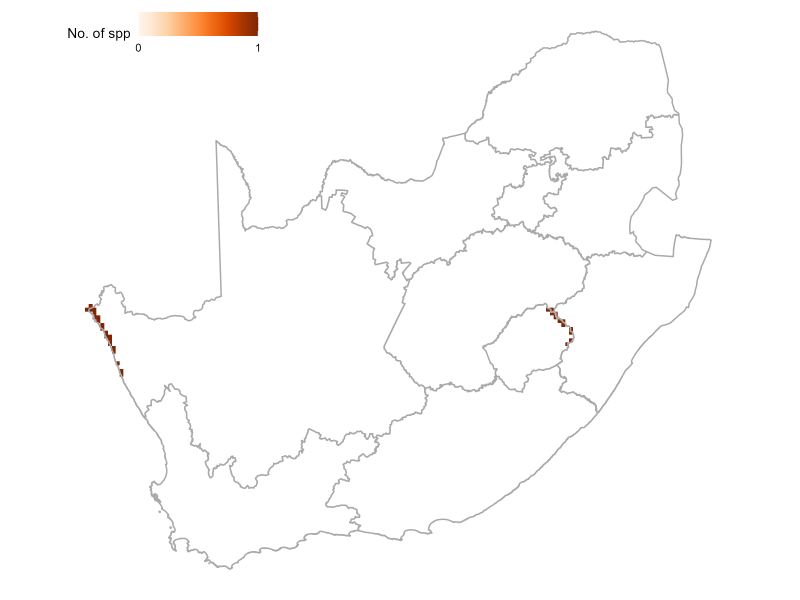

Almost 50% (17) of South Africa’s threatened amphibians occur in the Western Cape province. Given the high endemicity within this province, and the disproportionate number of endemic species that are threatened, this spatial pattern is not surprising.

Threat status

Seventy-six amphibian species (56%) are endemic to South Africa, with 30 of these (39%) threatened with extinction, placing full responsibility for their protection on South Africa. Most threatened species occur in, and are endemic to, the Western Cape (17 species), followed by KwaZulu-Natal (6 species) and then the Eastern Cape (4 species, Figure 1).

Twenty-two percent (30 species) of amphibians were assessed as threatened (Critically Endangered, Endangered, Vulnerable), and a further 10% (13 species) were assessed as Near Threatened (Figure 2, Table 1). There have been significant shifts in the number of species per category since the 2016 assessments, with 23% of species changing categories. Most of these have however been non-genuine changes such as improved accuracy in the application of the Red List criteria or because survey efforts resulted in better knowledge of the status of populations (see Box 1).

| Taxon | Critically Endangered | Endangered | Vulnerable | Near Threatened | Data Deficient | Least Concern | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall amphibians | 4 | 18 | 7 | 13 | 2 | 91 | 135 |

| Endemic amphibians | 4 | 17 | 5 | 11 | 2 | 36 | 75 |

Trends - the Red List Index

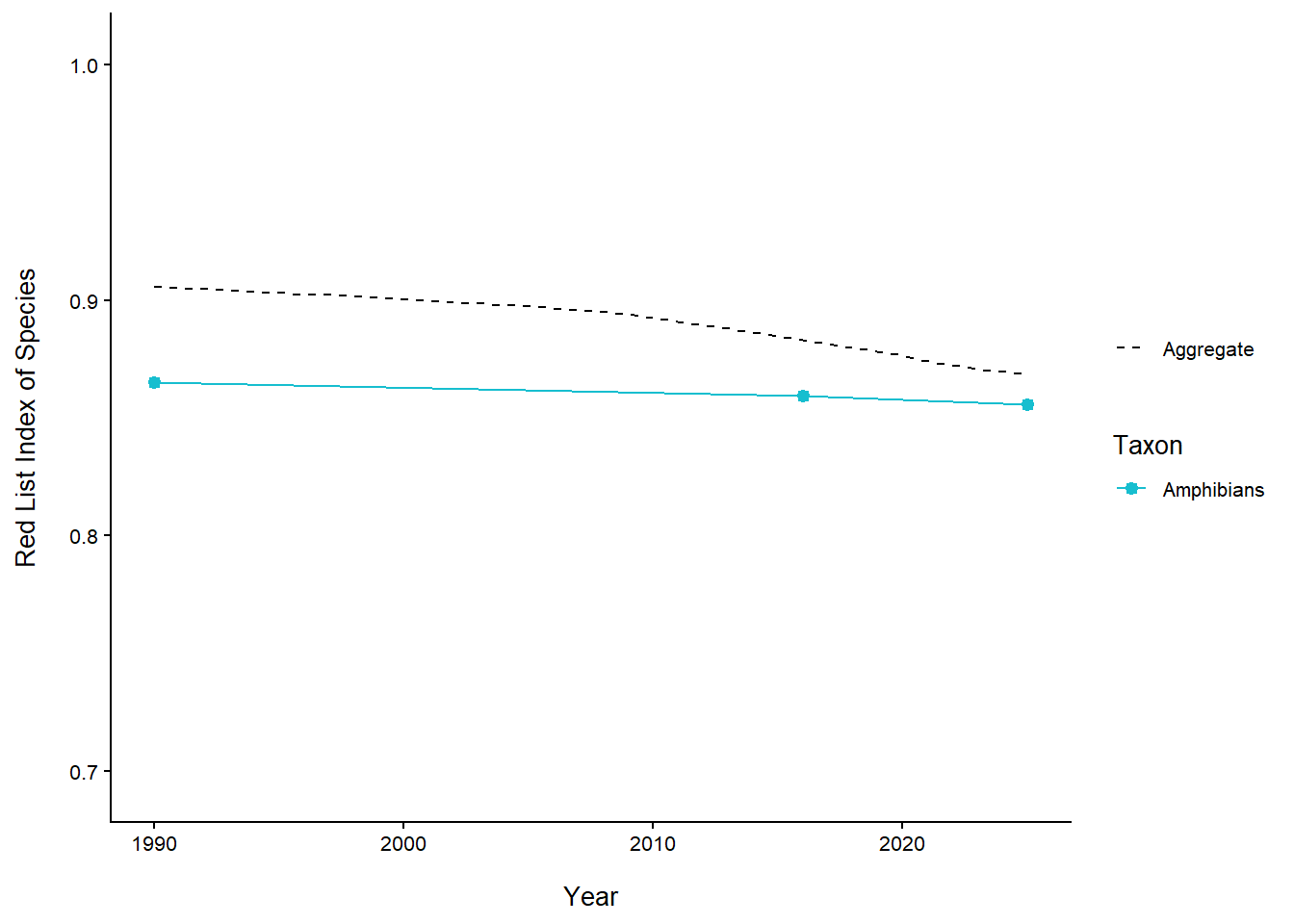

The trend in species status over time was measured using the globally recognised indicator, the IUCN Red List Index of species (RLI)2. The RLI are calculated based on genuine changes in Red List categories over time. The RLI value ranges from 0 to 1, and if the value is 1, all taxa are Least Concern, and if the value is 0, all taxa are extinct. The slope of the line show the rate at which the taxonomic group is heading towards extinction. The Red List Index of amphibians was calculated for all amphibian taxa that have been reassessed (n = 135, Figure 3).

Thirty species have had a change in status since the latest assessment (2016). However, only two of these are genuine changes: Breviceps macrops – desert rain frog (NT to VU) and Amietia hymenopus - Phofung river frog (NT to VU). These species are spatially isolated; however, they share some pressures, as both Breviceps macrops and Amietia hymenopus are likely to be impacted by climate change. The former is restricted to the dry West Coast of South Africa and relies on limited precipitation in the form of fog; and the latter occurs in streams along the Drakensberg Escarpment and Lesotho, which may face increased drying and extreme weather events (Figure 4). Both species are also impacted by the expansion of mining activities, B. macros specifically on the West Coast, due to the future planned development of Green Hydrogen and A. hymenopus in the highlands of Lesotho into South Africa (Table 2).

The remaining species that have had a change in their status were considered to be non-genuine changes due to new information, taxonomic changes, application of criteria, (see Box 1 for examples). There has been no improvement in the status of amphibians during the assessment period. Important to note is that amphibians remain threatened by pressures that have not ceased and are increasing in most instances. Of particular concern are the impacts of invasive alien species, which affect 83% of threatened species, particularly in cases where the spread of invasive species is continuing or increasing. Impacts of this threat include drying out and replacement of habitat by alien invasive plants, diseases such as chytridiomycosis, and competition with problematic native species (Box 2).

| Taxon | Change of Status (2016 to 2025) | Direction of change | Reason for change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amietia hymenopus** © Louis Du Preez |

NT to VU | Increase |

Deterioration in habitat quality, especially in Lesotho where active and proposed mines have had an observable increased impact (both directly and indirectly) on this species, with projected increased aridification due to climate change, overgrazing and water quality issues that have intensified since the last assessment, resulting in this species’ conservation status deteriorating.

|

| Breviceps macrops © Nick Telford |

NT to VU | Increase |

Based on projected increased threats from mining and development. New information on future threatening processes has become available with changes in government policy that will likely lead to increased industrial development in the coastal region of the Northern Cape, South Africa and southwestern Namibia.

|

Pressures

Globally, habitat loss is the most common threat to amphibians, impacting 93% of threatened species, with agricultural expansion being the leading cause of habitat loss and degradation5. For South Africa’s frogs, the main pressures driving declines are impacts from invasive species, affecting 76% of threatened and Near Threatened species (Figure 5). These impacts include replacement of natural habitat due to expansion of woody invasive plants, drying out of wetlands and streams, changes to stream dynamics, including sedimentation, and alteration of natural fire regimes.

This is followed by habitat loss and degradation due to modification of natural system (impacting 64% of threatened and Near Threatened species) and agricultural activities (impacting 57% of threatened and Near Threatened species). Modifications can exacerbate inappropriate fire cycles. Globally, climate change is now recognised as the most serious emerging challenge facing amphibians, with 29% of threatened species worldwide impacted. This threat is expected to affect more species in the future with projected increases in temperature and changes in precipitation. In South Africa, 38% of our threatened and Near threatened species are impacted, or projected to be impacted by climate change and extreme weather, through shifts in habitat, droughts and flooding (Figure 5). These impacts require data to improve predictive models of amphibian habitats; for example, species monitoring and climate data. Fourteen threatened species (33%) are affected by pollution, particularly from agricultural effluents and domestic and urban waste water. A good example is the subpopulations of the Kloof frog, (Natalobatrachus bonebergi), in Durban that are impacted by sewage overflows into streams and increased sedimentation from urban construction, where it has a severe impact on stream health and breeding sites. Even while this species has been downlisted from EN to NT due to overall EOO and the correct application of the criteria, the KwaZulu-Natal subpopulations face increasing levels of threat. These impacts reflect the state of South Africa’s freshwater ecosystems, with many systems currently assessed as modified (see freshwater ecosystem pressures).

Contributions of occurrence records of any species are extremely valuable and have made up a significant proportion of data used in the 2025 assessments (See Box 4).

Protection level

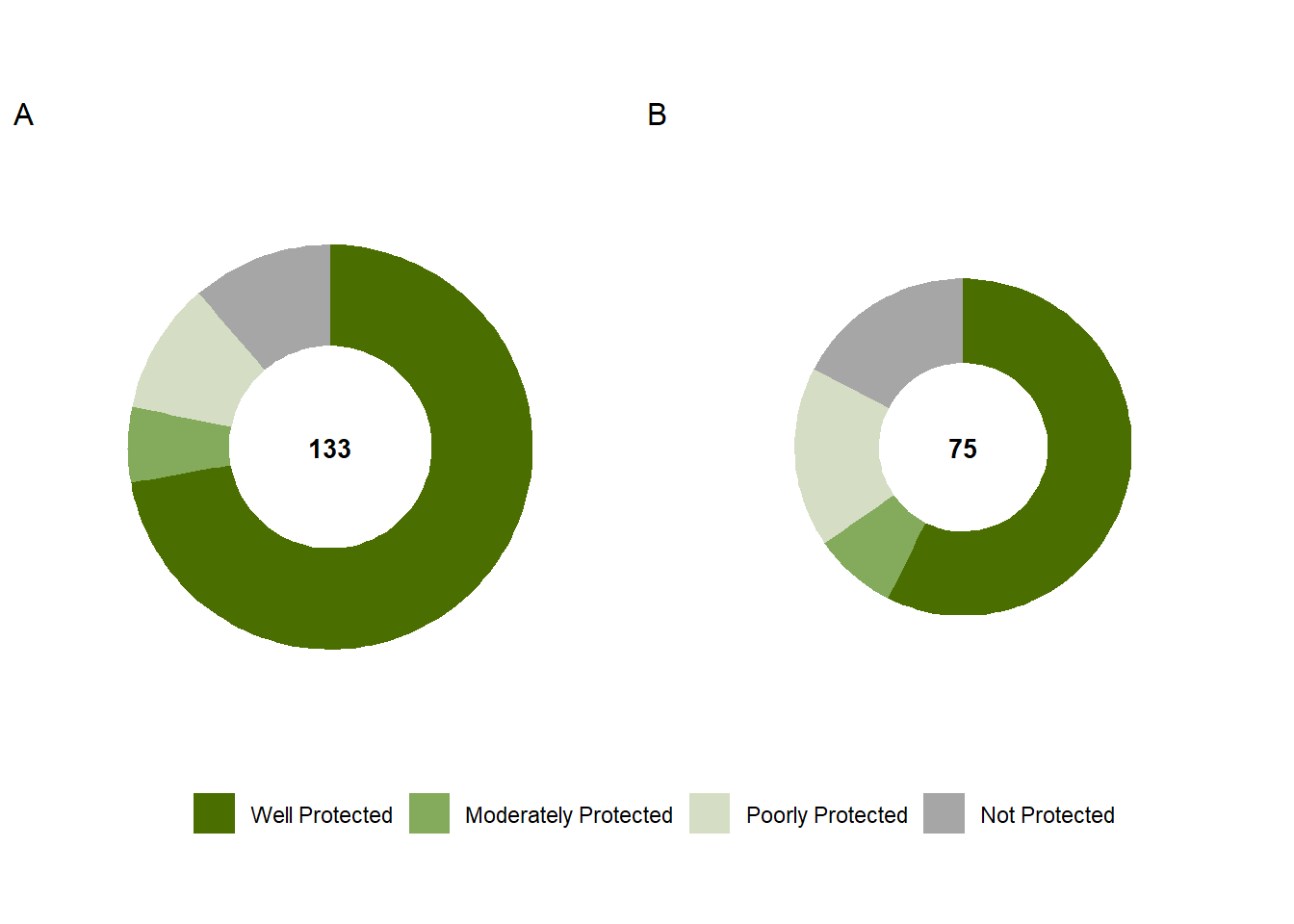

The protection level assessment was conducted for 133 of South Africa’s 135 described amphibian species (Figure 6). Two peripheral taxa with less than 5% of their distribution in South Africa were excluded from the analysis. Protection levels were calculated for amphibians by intersecting amphibian occurrence records with the protected area spatial layer, and calculating the area required to protect a target population of 10 000 individuals. Protection levels were also adjusted based on the management effectiveness of protected areas. For further details on the method used to conduct this assessment see here.

Overall, the 2025 protection level was higher than in 2016. While close to 72% of amphibians are considered Well Protected, 22% are Poorly or Not Protected. Species-specific management within protected areas is generally lacking for amphibians, with 7% (9 species) assessed as less well protected once protected area effectiveness is taken into account. For the 75 endemic amphibians assessed, 57% are Well Protected, 17% (13 species) are Not Protected, and a further 17% (13 species) are Poorly Protected. Sixteen highly threatened (CR and EN) species are under-protected (including Not Protected, Poorly Protected and Moderately Protected).

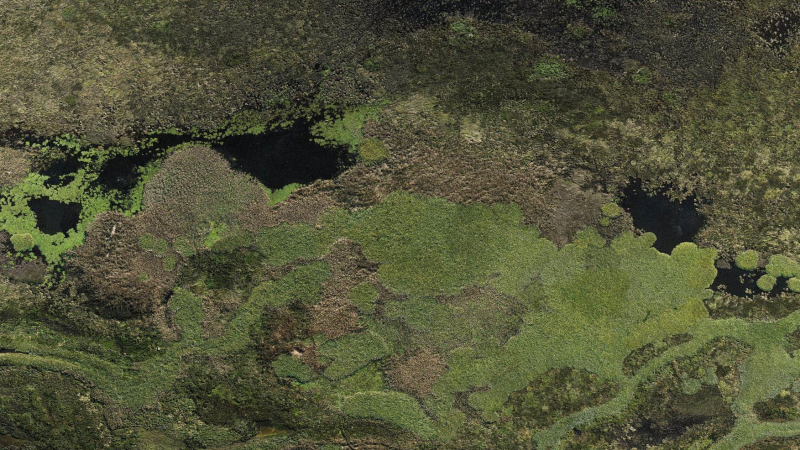

The mosaic of wetland habitat at the Nuwejaars Wetlands Special Management Area where the micro frog (Microbatrachella capensis) was discovered in 2021. Alien clearing efforts and population density estimates are currently underway using (M. capensis) as a management target. (© Keir Lynch Bionerds)

Nine species have had improvements in their protection level, from Poorly Protected to Moderately Protected (8 species) or Well Protected (1 species). Examples of threatened species that have benefitted from improved protection include the Endangered micro frog (Microbatrachella capensis), Pickersgill’s reed frog (Hyperolius pickersgilli), and the Cape platanna (Xenopus gilli). In the case of H. pickersgilli, an additional 16 sites have been confirmed for the species since 2017, with several of these occurring within protected areas7.

Habitat protection gains have been a key outcome of the coordination of the Biodiversity Management Plan for this species, with several sites (totalling 127 hectares) being declared through the Biodiversity Stewardship Programme, as well as improved management and wetland health for these, and existing protected areas7. For M. capensis, confirmation of the species in the Nuwejaars Wetlands Special Management Area in 2021, which is now being managed with the frog as a management target, has resulted in both an expansion of the species’ range with protected areas as well as improved management effectiveness scores from fair to good. It is important to recognise the contribution that Biodiversity Stewardship and conservation servitudes (or OECMs) makes to the protected area estate through agreements with landowners for targeting unprotected populations of species.

The previously Critically Endangered micro frog (Microbatrachella capensis), is now listed as Endangered due to its discovery at a new locality, it has also changed protection status from Poorly Protected to Moderately Protected resulting in a range extension. (© Alouise Lynch Bionerds)

Species recovery

As part of the Red List process for southern Africa, the Amphibian Ark (AArk) joined the expert workshop and worked with coordinators to produce a Conservation Needs Assessment (CNA) for threatened South African amphibian species8. This used a process developed by AArk to determine which species have the most urgent conservation needs, based on action plans that combine in situ and ex situ actions, as appropriate. Six South African species were identified for ex situ conservation actions, including ex situ rescue (n = 5) and ex situ research (n = 1). Due to their level of threat, the five species recommended for ex situ rescue are also recommended for biobanking. Twenty-five species were recommended for in situ conservation, and 34 species are recommended for in situ research, while 15 species were identified for conservation education programs.

In addition, subsequent work to identify species requiring urgent recovery under Target 4 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework resulted in 10 species being prioritised. This includes threatened endemic species and those of regional importance that might go extinct even if their habitat is protected. This highlights the limited targeted management of amphibians within protected areas and the need for research on how they respond to management interventions.

South Africa has a relatively proactive community working on amphibian conservation and research, with NGOs, provincial authorities and various universities contributing to building conservation evidence for assessing the effectiveness of conservation interventions and growing the body of knowledge on amphibian taxonomy, behaviour and ecology (Table 3). These activities were partially guided by the conservation and research strategy compiled following the 2010 Red List assessments9, demonstrating the value of these processes, with plans in place to update this strategy following the most recent assessments (2025). While progress has been made, amphibian conservation capacity remains overlooked and underfunded compared to other taxa10, and this is particularly pertinent in the African context, with limited resources in general, and the constant need to balance development needs with conservation efforts.

| Focal species | Organisation | Province(s) | Conservation Action | Get involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amathole Toad | EWT | EC | Habitat protection and management | https://ewt.org/ |

| Bilbo's Rain Frog | Anura Africa/NWU | KZN | Research on distribution, genetics and stakeholder engagement | https://www.anuraafrica.org/ |

| Kloof Frog | Anura Africa/NWU/Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife/EWT | KZN | Long-term monitoring; Research on ecology; water quality indicator | https://www.anuraafrica.org/ |

| Long-toed Tree Frog | Anura Africa/Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife/NWU | KZN | Building conservation evidence and population data using monitoring to inform habitat protection and management | https://www.anuraafrica.org/ |

| Micro Frog | Anura Africa/Grootbos Foundation/EWT | WC | Using bioacoustics to inform conservation management | https://www.anuraafrica.org/ |

| Moonlight Mountain Toadlet | EWT | WC | Habitat protection and management | https://ewt.org/ |

| Moss frogs (multiple species) | CapeNature | WC | Long-term monitoring | |

| Pickersgill's Reed Frog | Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife/Anura Africa/EWT | KZN | Implementation of actions through a coordinated Biodiversity Management Plan | https://www.anuraafrica.org/ |

| Rose's Mountain Toadlet | EWT/UCT/SANBI | WC | Improved management through stakeholder collaboration | https://ewt.org/ |

| Rough Moss Frog | EWT/CapeNature/Fynbos Trust | WC | Habitat protection and management | https://ewt.org/ |

| Table Mountain Ghost Frog | EWT/SANBI | WC | Improved management through stakeholder collaboration | https://ewt.org/ |

| Western Leopard Toad | SANBI/City of CT/EWT/Volunteer organisations/NatureConnect | WC | Genetic studies, road ecology, threat mitigation | https://natureconnect.earth/nature-care-fund/species-conservation/ |

Knowledge gaps

While amphibians globally remain the most threatened (41%) vertebrates on Earth, basic data on species distribution, population numbers, and ecology remain poor. This is likely partly a result of limited funding, with amphibians receiving the least conservation funding of all major groups globally. Less than 2.8% of funding support is directed to amphibians, and this has declined from 4% in the 1990s10. Projects on amphibians are also often focussed on multiple species, limiting per species investment. This differs from projects focussed on other taxa that often receive disproportional support, including for non-threatened species (e.g., large mammals). This lack of funding is likely the root cause of several knowledge gaps discussed below and is also linked to inadequate capacity in amphibian research and conservation. These gaps are even more acute outside of South Africa in other parts of the continent.

Similarly, despite major efforts in recent decades to improve knowledge on amphibian declines, there remains a disconnect between research and its translation into conservation actions. Research priorities identified at the global scale include a better understanding of the effects of climate change, community-level drivers of declines, methodological improvements for research and monitoring, genomics, and effects of land-use change. Improved inclusion of under-represented amphibian species in conservation projects was also highlighted4. In South Africa, growing amphibian conservation and research capacity in a more representative way is critical to addressing capacity gaps and providing skills transfer to young researchers to grow core conservation expertise.

Amphibian Red List assessments primarily apply criterion B (geographic range information). Research projects that generate population data, both over time and in response to threats and management interventions, will be useful to strengthen amphibian Red List assessments, and in turn to provide baseline data for adaptive conservation strategies. Using the outputs from Red List assessments, including recommended conservation and research actions, is crucial for prioritising and guiding future conservation strategies, and such strategies have been found to be effective in improving taxonomy, ecological studies, monitoring, research outputs, and capacity building11.

Approach

Threat status assessments

All previously assessed South African amphibians were reassessed as part of the Southern African Amphibian Red List Project (SAARLP) that commenced in 2023, as part the third global amphibian assessment process, supported by the IUCN Amphibian Specialist Group and Amphibian Red List Authority. A total of 135 species were assessed for publication on the IUCN Red List in 2025 and 2026, including 11 newly described species12. Over 150 000 records were collated for the assessments, including from various institutions and verified citizen science data. Twenty experts representing thirteen organisations contributed to the assessment process.

See details about how the IUCN Red List assessments are conducted here.

Protection level assessments

The species protection level assessment measures the contribution of South Africa’s protected area network to species persistence. It evaluates progress towards the protection of a population target for each species, set at the level of protection needed to support long-term population survival.

Amphibian protection level was assessed for NBA 2018 and was repeated in 2025 using updated species occurrence data based on the 2025 Amphibian Red List Reassessment. A spatial layer of protected areas for 2018 and 2025 representing protected areas that were declared at that time were used for the two time periods. A technical report outlining the full methodology and limitations will be available in February 2026.

See details about how the protection level indicator was conducted here.

Acknowledgements

Contributors

| Contributor | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Adriaan Jordaan | University of the Western Cape, Iziko South African Museum |

| Adrian John Armstrong | Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife |

| Andrew Turner | Cape Nature |

| Anisha Dayaram | South African National Biodiversity Institute |

| Carol Poole | South African National Biodiversity Institute |

| Che Weldon | North-West University |

| Darren Pietersen | Endangered Wildlife Trust |

| Fortunate Mafeta Phaka | North-West University |

| Francois Stephanus Becker | Gobabeb Research and Training Centre, National Museum of Namibia, University of Cape Town, University of the Witwatersrand |

| James Harvey | Harvey Ecological |

| John Measey | Centre for Invasion Biology, Stellenbosch University |

| Keir Lynch | Anura Africa;Bionerds |

| Krystal A. Tolley | South African National Biodiversity Institute |

| Louis Heyns Du Preez | North-West University |

| Luke Verburgt | Enviro Insight |

| Mohlamatsane Mokhatla | University of Pretoria |

| Nieto Lawrence, J. A. | Anura Africa; University of Johannesburg |

| Ninda Baptista | Universidade do Porto, Portugal |

| Oliver Angus | Endangered Wildlife Trust (at the time of assessments) |

| Werner Conradie | Port Elizabeth Museum |

Recommended citation

Tarrant, J., Weeber, J., Raimondo, D.C., Monyeki, M.S., Van Der Colff, D., & Hendricks, S.E. 2025. Amphibians. National Biodiversity Assessment 2025. South African National Biodiversity Institute. http://nba.sanbi.org.za/.

Moonlight Mountain toadlet (Capensibufo selenophos). (

Moonlight Mountain toadlet (Capensibufo selenophos). ( Boston rain frog (Breviceps batrachophiliorum). (

Boston rain frog (Breviceps batrachophiliorum). ( Table Mountain ghost frog (Heleophryne rosei). (

Table Mountain ghost frog (Heleophryne rosei). (