Pressures on ecosystems and species

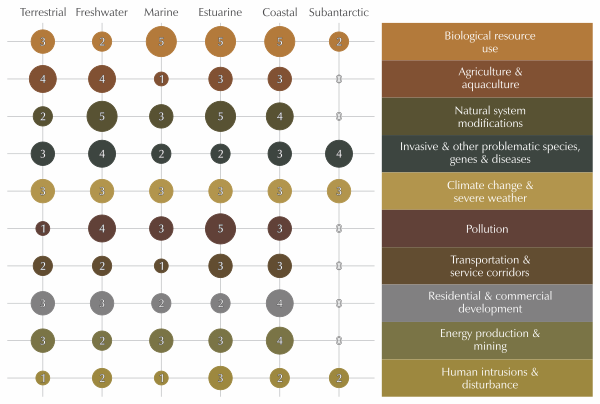

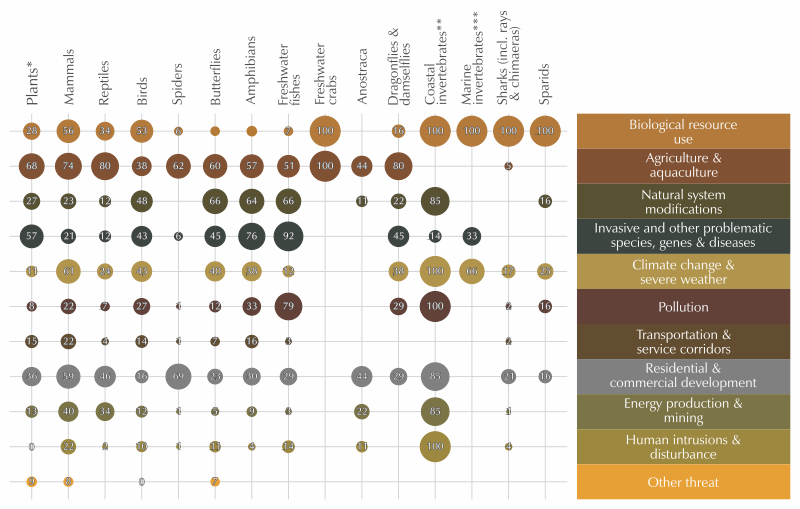

The IUCN proposes a threats classification scheme with a hierarchical structure for various pressures on biodiversity. The NBA 2025 adopted this approach with some minor language changes. Figure 1 is for the realms, the coast and the subantarctic, and Figure 2 is for taxonomic groups.

In the estuarine and marine realms, and in coastal areas, unsustainable use of biological resources (in this case overfishing of key species, along with associated impacts on non-target species) is a significant pressure on biodiversity (key messages A5 and A6). There is increasing illegal harvesting and trade of numerous high value species in the terrestrial and aquatic realms, with population declines and near extinction of several species. Overuse of rangelands, which results in loss of shrub and herbaceous cover and leads to increased erosion, is a direct pressure to terrestrial species and ecosystems and an indirect pressure on freshwater ecosystems.

Modifications to natural systems such as changes in hydrological regime are major pressures on biodiversity in freshwater, estuarine, many coastal and selected terrestrial ecosystems (key message A7). Over-abstraction of water and dam construction have direct negative impacts on species and ecosystems, and indirect impacts through disruption of important ecological processes such as sediment supply.

Changes to fire regimes linked to management imperatives, climate (drought events and high winds) and an increase in fuel loads from invasive alien plants are important natural system modifications in the terrestrial realm that have a detrimental impact on biodiversity. Species that have evolved special adaptations to survive fire, such as certain lycaenid butterflies and Fynbos plants, struggle to cope with fires that have increased intensity and occur more frequently than in the past. South Africa’s iconic Brenton blue butterfly has likely gone extinct as a result of high invasive plant fuel loads in the Garden Route region of South Africa coupled with climate change linked intense wildfires.

Pollution of aquatic ecosystems from a combination of acid mine drainage, mining, industrial and urban wastewater, stormwater, as well as agricultural return flows, negatively impact water quality (key message A3). When combined with flow regime changes, pollution represents a major additional pressure on freshwater, estuarine and coastal biodiversity. For example, freshwater bird species are becoming more threatened due to pollution.

Climate change is an accelerating threat across all realms, and amplifies other pressures such as invasive species, disease, habitat loss, flow reduction and habitat degradation (key message A1). Climate change may also be associated with more severe or extended droughts. Multiple indigenous terrestrial species from the western arid regions of South Africa have experienced significant population declines as a result of a severe extended drought over the past decade. Though impacts of climate change on biodiversity are best understood in the terrestrial realm, coastal and estuarine ecosystems are particularly at risk from extreme weather events, especially where human settlements limit the natural resilience of these ecosystems by encroaching into dune systems and the Estuarine Functional Zone.

Habitat loss as a result of land clearing for croplands, plantation forestry, human settlements and mining is the primary pressure in the terrestrial realm (key message A2). Mining is one of the main drivers of increased risk of extinction for reptiles, mammals, amphibians and plants, and several coastal ecosystem types in Namaqualand. Intensive agriculture, in the form of croplands and pastures, significantly impacts most terrestrial and freshwater species groups assessed to date.

Biological invasions impact all realms, with predatory alien fishes substantially impacting indigenous fish species in rivers (key message A4). A wide range of woody invasive plant species impact riverine areas, wetlands and mountain catchments in particular and cause severe declines to South Africa’s indigenous plants and amphibians.

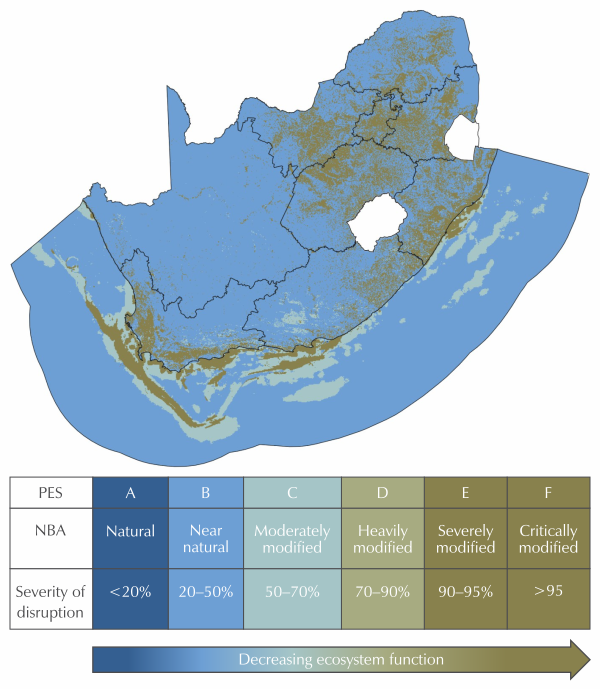

Ecological condition across realms

Ecological condition is estimated using a range of different approaches across the realms, but is essentially the product of spatially representing the various pressures exerted on biodiversity. Ecological condition in the terrestrial realm relies primarily on land cover change, invasive species and overgrazing data; cumulative pressure mapping is used in the marine realm; and a multi-criteria ecological condition framework is used in the estuarine and freshwater realms. The different systems were aligned as far as possible in the NBA to allow for cross-realm comparisons of ecosystem condition and unified terminology.

The marine and terrestrial realms are similar in terms of their relatively high percentage of natural/near-natural ecosystem extent (~70%). In these extensive realms, ecosystem modification tends to be focussed in pressure hotspots, usually linked to local characteristics such as high productivity, accessibility and valuable natural resources; while large areas remain relatively unmodified or intact (Figure 3). For example, the Cape lowlands have extensive winter field crops while the mountainous areas of the Cape see far less intensive agriculture; all bay ecosystem types, the shelf edge and the KwaZulu-Natal Bight are subject to multiple pressures while many deep-sea ecosystems beyond the shelf have yet to see extensive modification.

In stark contrast, freshwater wetlands and rivers, as well as estuaries, are predominantly heavily modified, and in poor ecological condition (key message B2). These realms are geographically constrained, and pressures tend to concentrate. Only 18% of estuarine area, 49% of wetland area and 25% of river length are considered to be in natural/near-natural condition. Coastal biodiversity is also under particularly high pressure and approximately half of the ecologically determined coastal zone remains in a natural/near-natural condition.