of 191 species assessed are

Threatened

of 191 species assessed are

Endemic

Key findings

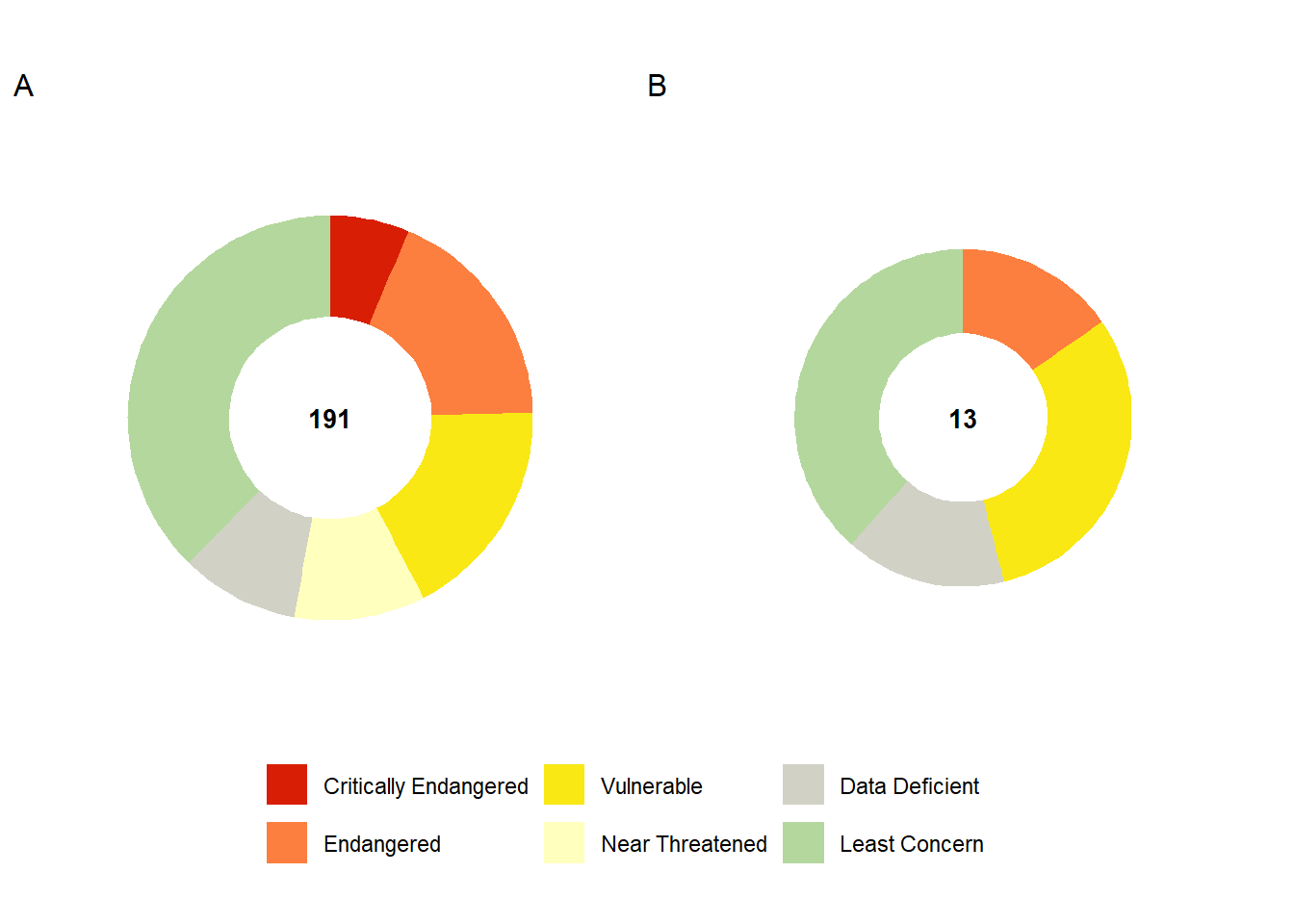

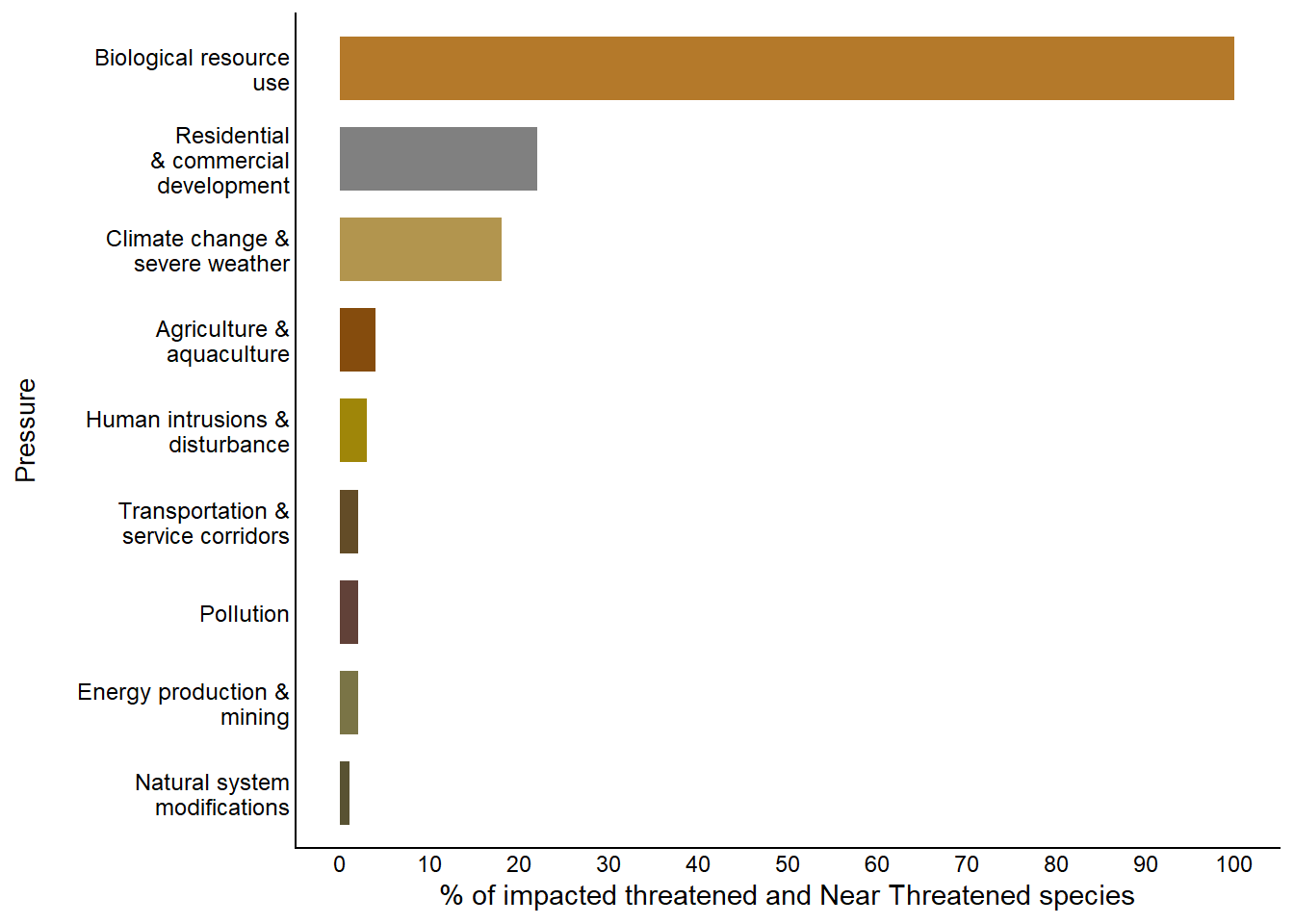

191 species of sharks, rays and chimaeras have been assessed, with 13 of these species endemic to South Africa.

Forty-three percent (82 species) of these are threatened with extinction, with another 10% (20 species) assessed as Near Threatened.

Six of South Africa’s 13 endemic sharks are threatened with extinction, placing full responsibility for their protection in South Africa.

Sharks have been included in the South African Red List Index (RLI) for the first time. Sharks are the most threatened marine taxonomic group in South Africa, and they have the lowest RLI score of all South African taxon groups assessed.

The main threats to sharks are fisheries, primarily as targeted catch and bycatch in commercial fisheries. Habitat loss and degradation are also identified as a threat to several species with small geographic ranges in nearshore and coastal habitats (including endemic species). Climate and oceanographic changes are likely driving habitat loss and range shifts for some species.

Overview of diversity

Sharks, rays and chimaeras (hereafter ‘sharks’) are members of the diverse class of cartilaginous fishes that includes the sharks, rays, skates, sawfishes and chimaeras (or ghost sharks).

South Africa hosts one of the richest and most diverse shark assemblages in the world. Globally, there are approximately 1 266 species, of which 191 are found in South African waters, including 13 endemic species1. This assemblage represents important ecological and cultural values as well as commercial value2.

South Africa’s sharks range in size from smaller species such as the happy Eddie (Haploblepharus edwardsii) at up to 60 cm to the white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) at up to 6 meters total length. Some shark species, such as the happy Eddie , are resident, spending their entire life cycles in South African waters; whereas others, such as the white shark, are highly mobile and may face significant threats well beyond South African waters3.

Sharks occupy a diversity of habitats from estuaries and shallow coastal waters (including sandy and muddy seabeds, coral and rocky reefs, and kelp forests) to deeper offshore waters (including both benthic habitats and the pelagic zone).

Sharks perform a range of essential ecological functions – as apex and meso-predators sharks influence marine ecosystems in multiple ways. By limiting the abundance, behaviour, and distribution of their prey, they help stabilise food webs, support diversity at lower trophic levels, and maintain the ecological processess that underpin healthy ocean systems. Large benthic rays can serve as habitat engineers and important bioturbators, making oxygen and buried nutrients available to other organisms4. The importance of sharks in maintaining well-functioning coastal and marine ecosystems cannot be overemphasised5.

Many shark species are long-lived, slow growing, and late maturing with low reproductive rates. These characteristics combine to make shark populations inherently vulnerable to overfishing and slow to recover following depletion.

Species with small geographic ranges in nearshore and coastal habitats are also especially vulnerable to habitat loss and degradation, and some appear to be undergoing climate-induced range shifts that may reduce their geographic range still further.

In Global Priorities for Conserving Sharks and Rays: A 2015–2025 Strategy6, South Africa was identified as a priority country for saving shark species, based on an analysis of species richness, threat, levels of endemism, and likelihood of conservation success.

Threat status

Based on the combination of global and national IUCN Red List of Threatened Species assessments (see Approach), 82 species (43%) were found to be threatened (Figure 1, Table 1), including 12 species (6%) listed as Critically Endangered, 35 (18%) as Endangered, and 35 (18%) as Vulnerable. A further 20 species (10%) are categorised as Near Threatened, while 18 (9%) are classified as Data Deficient, with insufficient information to determine threat status. 71 species (37%) are categorised as Least Concern. Six (46%) of the 13 endemic species were assessed as threatened. Responsibility for the conservation and recovery of these six species lies in South Africa’s hands.

For the species assessed at the national level, 11 species are assessed as less threatened at the national than global level (including five species that are globally threatened but nationally Least Concern) and 21 species have the same threat status at global and national levels. These results indicate that South Africa’s efforts to manage fisheries for some target and bycatch species are having significant positive impacts, while the overall status assessment (43% of South Africa’s sharks listed as threatened) shows that much more still needs to be done to prevent extinctions and foster recovery.

| Taxon | Critically Endangered | Endangered | Vulnerable | Near Threatened | Data Deficient | Least Concern | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall sharks | 12 | 35 | 34 | 20 | 18 | 72 | 191 |

| Endemic sharks | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 13 |

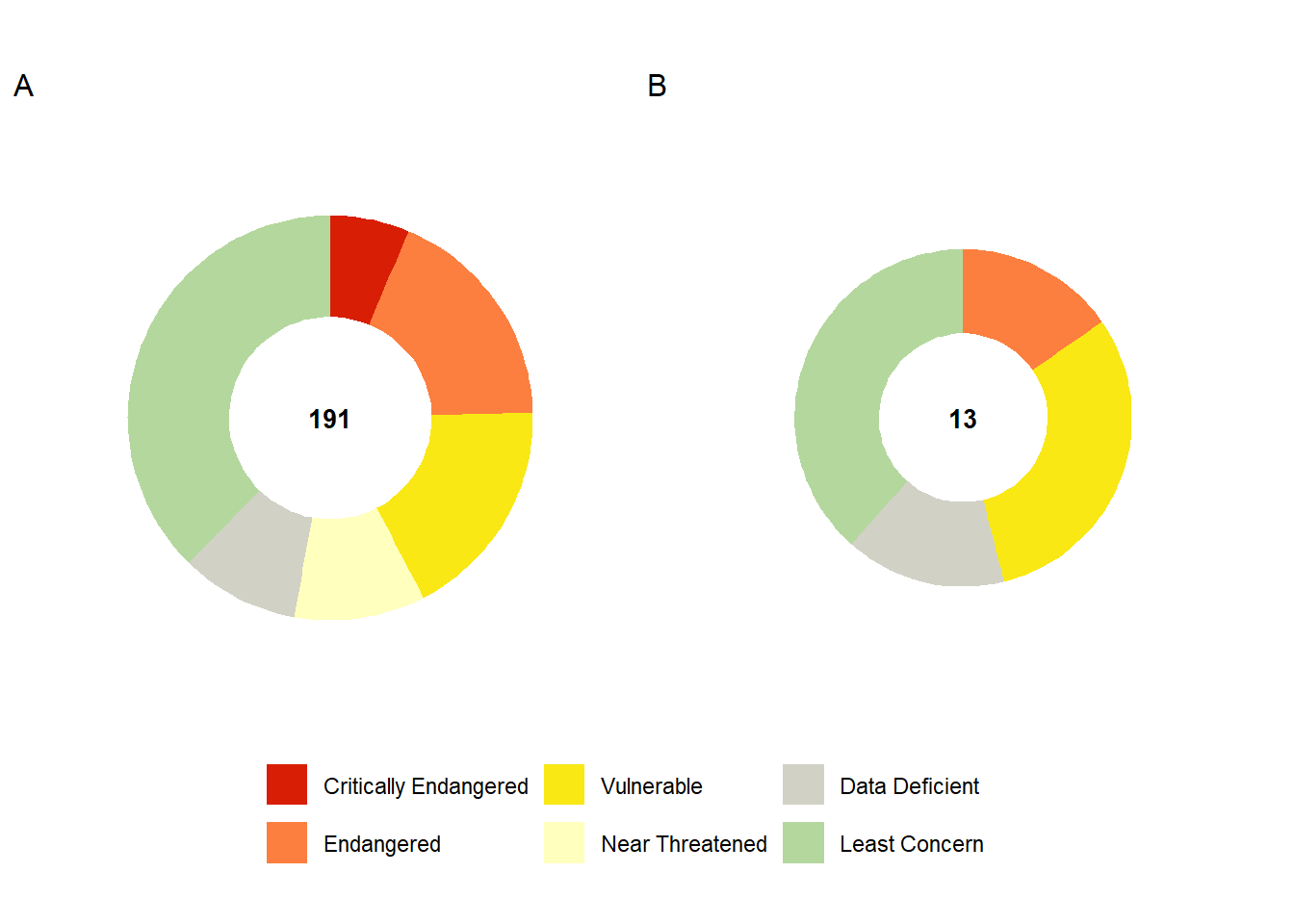

The shark RLI shows that many of South Africa’s shark species were already threatened in 2005 (Figure 2). The RLI declined further between 2005 and 2020, meaning that South Africa’s shark species continued to move towards extinction.

The declining status of sharks is a global trend7, with steeper declines in the global RLI since 1970 than for any other marine taxonomic group except for stony corals. As most of South Africa’s 191 shark species have ranges that extend well beyond South African waters, some of the decline in the RLI for South Africa’s sharks reflects intense fishing pressure and other threats beyond South Africa’s jurisdiction. When national adjustments in threat status are taken into account, the overall national status of South Africa’s sharks is marginally better than their global status and the decline in the national RLI is marginally less steep than the global RLI for the same set of species (Figure 2). As for the overall threat status, these results indicate that South Africa’s efforts to manage fisheries for some target and bycatch species are having significant positive impacts, but that much more still needs to be done to prevent extinctions and foster recovery.

Pressures

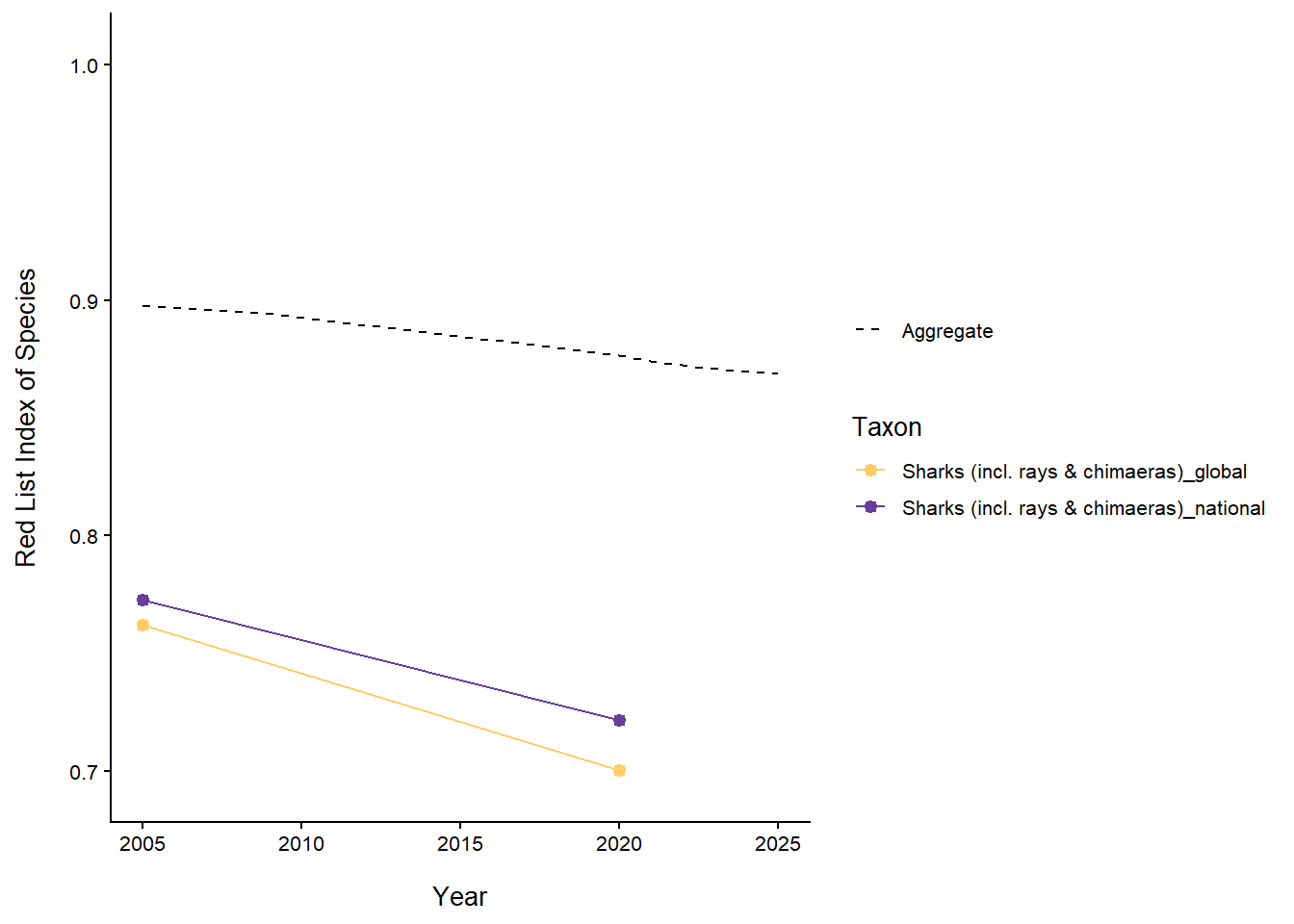

Overfishing is the main threat to sharks globally8 and in South Africa (Figure 3). Overfishing has been identified as a major threat on the IUCN Red List for all of South Africa’s threatened shark species and is the main threat identified for two thirds of those species. This includes targeted catch in some commercial fisheries, plus bycatch in commercial fisheries targeting more productive species, recreational fisheries, lethal shark control measures, and ghost fishing by abandoned fishing gear.

Total catches of sharks across all fisheries have been decreasing and are now in the order of 1 000 tonnes per annum5. Domestic consumption of shark meat and fins in South Africa is limited – most of the documented catch is exported to markets in Asia, Latin America and Australia.

Among shark species landed in South African fisheries, 24% are Critically Endangered (Table 3) or Endangered. Two of these species have estimated annual catches (2013-2023) in excess of 100 tonnes9: soupfin shark (Galeorhinus galeus, CR) and shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus, EN). An additional four Endangered species have estimated average annual catches (2013-2023) of 11 tonnes or more9: dusky shark (Carcharhinus obscurus, EN), the endemic twineye skate (Raja ocellifera, EN), spearnose skate (Rostroraja alba, EN), and common smooth-hound (Mustelus mustelus, EN) (Table 2). For most of these species (the exception being the spearnose skate), overfishing is the main pressure. However, catches are very low for five of the Critically Endangered or Endangered species landed in South African fisheries5.

From 2010 to 2012, approximately two thirds of the reported shark catch in southern Africa was bycatch10. While some bycatch is retained and sold, much unwanted bycatch is discarded at sea. Mortality rates are high for many bycatch species, especially if they are neglected while on deck. Bycatch discarded at sea is effectively unrecorded and unregulated5.

Recreational fisheries continue for some shark species – while fishers may choose catch-and-release, post-release mortality rates are high for some species due to high capture stress (e.g. the Critically Endangered scalloped hammerhead, Sphyrna lewini). The impact of recreational fishing also extends to threatened shysharks and catsharks, which are caught as bycatch why fishers target other species. They are often discarded on the shore because they are viewed as pests.

The lethal shark control programme in KwaZulu-Natal (shark nets and baited drum lines for bather protection) targets large sharks and represents an additional pressure on target and bycatch species. Currently, the programme is responsible for 2.4% of South Africa’s total shark catch5. The lethal shark control programme is the main pressure in South Africa for the Critically Endangered great hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran) and the Endangered sandbar shark (Carcharhinus plumbeus), and also takes the Critically Endangered scalloped hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini). While some individuals are released alive, some species (such as hammerheads) have high capture stress and are unlikely to survive. See lethal shark control measures section on the marine pressure page.

By combining long-term catch records from the demersal and pelagic shark longlines and the KZN lethal shark control programme with satellite-tracking data for white sharks, there is evidence that these bather protection measures have caught more white sharks than assessed commercial fisheries11.

South African fisheries are well developed, with a high degree of industrialisation10. Threats to sharks, rays and chimaeras associated with small-scale fisheries are likely lower in South Africa than in some other coastal countries in the region.

Pressure from illegal gillnet fisheries in estuaries and the open sea along the entire South African continental margin is growing, representing an increasing threat to both legal fisheries and sharks9. In some areas, catches and landings of sharks in illegal gillnets at sea likely exceed landings from legal gillnets9. The illegal gillnet fishery is characterised by exceptionally high bycatch, especially when nets are set in estuaries and other nursery areas9.

While South Africa’s industrial fisheries are well managed and various measures are in place to reduce pressure on threatened species, many sharks are highly mobile and face more intense fishing pressure when they leave South African waters, including unregulated and illegal fishing12.

One quarter of South Africa’s threatened shark species are threatened by habitat loss and degradation attributed to coastal development and pollution (see marine pressures page). This is a major threat for many geographically restricted and ecologically specialised species that depend on nearshore and coastal ecosystems such as estuaries, mangroves and seagrass beds (including several threatened endemic species; Table 2). Even broadly distributed highly mobile species typically depend on particular sites and habitats for some life-cycle processes, such as breeding and feeding, and may be vulnerable to degradation of those habitats.

The effects of climate change are difficult to determine, but one fifth of South Africa’s threatened shark species are considered threatened by climate-driven habitat loss or range shifts. Climate pressure may be mediated through direct impacts on habitat loss (e.g., loss of coral reef habitat through bleaching for the Critically Endangered shorttail nurse shark, Pseudoginglymostoma brevicaudatum) or through range shifts in response to changing ocean temperatures and other oceanographic variables that can lead to significant habitat loss for geographically restricted and ecologically specialised species, including several of South Africa’s threatened endemic species (Table 2; see also Pollom et al. 2024).

Focus on South Africa’s threatened endemic shark species

The main threat identified for the six threatened endemic species is fisheries – two species are subject to target catch effort, while all six are taken as bycatch in fisheries targeting other species (Table 2).

| Species | Fisheries | Habitat loss and degradation | Climate change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tiger catshark (Halaelurus natalensis, VU) | Bycatch in demersal trawl, longline, beach seine, gillnet, and squid fisheries; also caught in recreational line fisheries | Range shift attributed to climate change, likely representing a significant loss of habitat | |

| Happy eddie (Haploblepharus edwardsii, EN) | Bycatch including beach seine, gillnet, trawl, recreational and commercial line, rock lobster, and demersal shark longline fisheries | Range shift likely attributable at least partially to climate change, possibly leading to loss of habitat; hatching rate of egg cases is temperature-specific and potentially sensitive to climate change | |

| Brown shyshark (Haploblepharus fuscus, VU) | Bycatch in trawl fisheries, and commercial and recreational line fisheries | Housing and urban development | |

| Natal shyshark*(Haploblepharus kistnasamyi, VU) | Bycatch in demersal trawl and recreational and commercial line fisheries | Commercial and industrial areas, tourism and recreation areas, domestic and urban waste water pollution | |

| Twineye skate (Raja ocellifera, EN) | Bycatch and retained catch including trawl, commercial and recreational line, beach seine, and gillnet | ||

| Flapnose houndshark* (Scylliogaleus quecketti, VU) | Caught occasionally by the recreational hook-and-line fishery. | Coastal development and pollution |

Focus on Critically Endangered shark species that occur in South Africa

Many of the globally threatened shark species that occur in South African waters have broad global ranges and face varying pressure across their ranges. Some of the pressures shown in Figure 3 may not be prevalent in South Africa. Table 3 summarises the pressures on 12 Critically Endangered shark species, focusing on pressures in South African waters. The Critically Endangered soupfin shark (Galeorhinus galeus) still faces pressure from fisheries, with an annual catch of more than 100 tonnes in South Africa alone.

| Species | Estimated average annual catch 2013-2019 in tonnes (DFFE 2022, Appendix II) | Fisheries | Notes on major threats in South African waters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soupfin shark (Galeorhinus galeus, CR) | 101-200 tonnes with 101-400 tonnes reported for 2010-2012 | Demersal shark longline, Demersal trawl, Commercial line fishery | Catches are dominated by the demersal shark longline fishery, the inshore demersal trawl fishery and the commercial line fishery. There is currently limited protective legislation in the form of slot limits which only allow the retention of individuals between 70 and 130 cm. A species-specific fisheries management plan is needed. |

| Scalloped hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini, CR) | 1-10 tonnes | Recreational linefish, KwaZulu-Natal shark control programme, Small pelagic and midwater trawl | The KwaZulu-Natal lethal shark control programme is the largest contributor, followed by demersal trawling and prawn trawl fishery. It is also caught in the recreational line fishery, but catches are not recorded. It is also suspected catch in the pelagic longline, demersal longline and commercial line fishery. |

| Great hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran, CR) | <1 tonne with 1-10 tonnes reported between 2010-2012 | KwaZulu-Natal shark control programme | The KwaZulu-Natal lethal shark control programme is the only definite contributor. It is suspected catch in the pelagic longline, and commercial and recreational line fisheries. |

| Oceanic whitetip shark (Carcharhinus longimanus, CR) | <1 tonne | Pelagic longline and Small pelagic and midwater trawl | Pelagic longlining is the major component, followed by the small pelagic fishery. Globally, this species has experienced enormous and prolonged fishing pressure and is now rare in many places. |

| Bowmouth guitarfish (Rhina ancylostomus, CR) | It was not listed in estimated catches recorded by DFFE for the period 2010–2012. This species was a bycatch in the now closed KwaZulu-Natal prawn trawl fishery on the uThukela Banks and is infrequently caught by the KwaZulu-Natal lethal shark control programme and by shore anglers. | ||

| Largetooth sawfish (Pristis pristis, CR) | Previously caught in small numbers by recreational anglers and in the KwaZulu-Natal lethal shark control programme, and probably by illegal gillnets. No recently reported local catches; the last known sawfish catch occurred in the KwaZulu-Natal lethal shark control programme in 1999. Estuarine degradation likely contributed to declines. | ||

| Green sawfish (Pristis zijsron, CR) | Previously caught in small numbers by recreational anglers and in the KwaZulu-Natal lethal shark control programme, and probably by illegal gillnets. No recently reported local catches; the last known sawfish catch occurred in the KwaZulu-Natal shark control programme in 1999. Estuarine degradation likely contributed to declines. | ||

| Ornate eagle ray (Aetomylaeus vespertilio, CR) | First confirmed in South Africa in 2018. No recorded catches in South Africa. | ||

| Shorttail nurse shark (Pseudoginglymostoma brevicaudatum, CR) | First recorded in South Africa in 2020. No recorded catches in South Africa. It has experienced heavy fishing pressure elsewhere in its range and loss of coral reef habitat. | ||

| Spinetail devil ray (Mobula mobular, CR) | 1-10 tonnes for Mobula spp. | KwaZulu-Natal shark control programme and Pelagic longline fishery | This species is rare in South African waters and hard to distinguish from conspecifics. |

| Bentfin devil ray (Mobula thurstoni, CR) | This species is rare in South African waters and hard to distinguish from conspecifics. | ||

| Sicklefin devil ray (Mobula tarapaca, CR) | This species appears to be uncommon in South African waters and is hard to distinguish from conspecifics. |

Addressing pressures

Management measures are essential to address threats to sharks, prevent overfishing and halt the progressive decline of shark populations towards extinction. Such measures can support the conservation and recovery of South Africa’s shark biodiversity, maintain livelihoods based on sustainable fisheries, and ensure that sharks continue to play their critical roles in maintaining well-functioning coastal and marine ecosystems. These measures are all part of South Africa’s commitment to the global community to address biodiversity loss through the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, especially Target 4 (halting species extinctions), Target 5 (sustainable use of wild species, preventing overexploitation), Target 9 (sustainable management of wild species for the benefit of people) and Target 2 (restoration of degraded ecosystems). See priority actions in the marine chapter for more information.

Progress to date

South Africa has made significant progress in addressing threats to sharks through the following measures:

Data collection and analysis

- Good data collection and data management are essential for effective fisheries management. South Africa undertakes fisheries-independent surveys, catch and effort data collection in various fisheries, analysis of population trends and distribution patterns for selected species, stock assessments for a small number of species. There have also been many efforts to improve the identification of sharks which improves data quality5.

Spatial measures

Sharks need a refuge from fishing pressure. Marine protected areas (MPAs), other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) and other special protection measures designed to safeguard sharks and their habitat within a delineated space can play an important role in safeguarding nursery grounds and other essential habitats. Such measures are most relevant to resident species, but even highly mobile species often depend on specific sites for one or more key life-cycle processes and may be philopatric.

South Africa has established a network of coastal and offshore MPAs – while designed to safeguard a broader set of biodiversity, some of these are located in sites where they can protect sharks and important parts of their habitat. Existing MPAs that safeguard important shark habitat include the uThukela Banks, an important nursery areas for several shark species, Protea Banks, which is a known aggregation site for several species, and the Southwest Indian Seamount MPA, which incorporates habitats identified as globally significant for the conservation of shark species in the region2.

Fisheries-wide measures

Fisheries-wide measures are usually applied to all vessels or permit-holders within a particular fleet (e.g., entry permits, catch limits, size limits, gear restrictions, catch-and-release protocols, trade restrictions). South Africa has implemented various fisheries-wide measures, including:

prohibition of nine threatened species in commercial and/or recreational fisheries,

the demersal hake trawl fishery has ringfenced its footprint, and no longer trawls outside of these established trawl areas,

the crustacean trawl fishery in KwaZulu-Natal has reduced its footprint and no longer trawls in shallow water due to the establishment of the uThukela MPA,

South Africa prohibits squalene production which has helped to prevent targeting of deep-water squalid sharks,

permit conditions that penalise vessels with high bycatch,

size limits in the demersal shark longline fishery,

daily bag limits in recreational fisheries,

shift from large-mesh gillnets to more selective baited drumlines (i.e. baited hooks suspended from buoys anchored to the seabed) in lethal shark control programmes and removal of gillnets from most beaches during the winter months to reduce bycatch of predators associated with the sardine run and prevent entanglement of whales.

Water quality and flows

- Measures to restore water quality and flows (see key message A7)

Future needs

Not withstanding the above, the persistent high proportion of South Africa’s shark species that are Critically Endangered or Endangered (47 species, 25%) and the declining trend in the RLI for South African sharks indicate that the measures need to be expanded, strengthened, or improved.

Spatial measures

Important sites for sharks should be prioritised in any plans to expand and improve management of MPAs, OECMs and other special protection areas, given the high and deteriorating threat status of sharks. Information on important sites for sharks can be gained through the widely respected expert-derived Important Shark and Ray Area (ISRA) process16, Key Biodiversity Areas17 and other approaches (e.g., systematic conservation planning18.

Much can also be achieved by expanding the areas within existing MPAs where fisheries that take sharks are restricted or must adopt special measures to prevent capture of threatened sharks18.

Important sites that are not protected through MPAs or OECMs can be incorporated into Critical Biodiversity Areas. In addition to MPAs and OECMs, other spatial conservation and management processes, including Environmental Impact Assessments, estuarine management plans, and integrated coastal management plans, need to be directed to consider shark conservation2.

Fisheries management for target species

Additional investments are needed to ensure sustainable science-based fisheries management for target species that takes account of the ecosystem effects of shark removals, given the important roles of sharks in coastal and marine ecosystems. This includes specific actions to address excess catch, including a shift from lethal shark control to non-lethal bather protection programmes and increased investment in monitoring and enforcement of existing regulations.

In particular, stronger measures are needed to protect the six Critically Endangered and Endangered species that were subject to average annual catches of 11 tonnes or more in the 2013-2023 period (i.e. soupfin shark (Galeorhinus galeus, CR), shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus, EN), dusky shark (Carcharhinus obscurus, EN), the endemic twineye skate (Raja ocellifera, EN), spearnose skate (Rostroraja alba, EN), common smooth-hound (Mustelus mustelus, EN))9.

Bycatch

Most notably, increased investment is urgently needed to reduce the excessive rates of shark bycatch in South Africa’s fisheries and shift towards more selective fishing gears and practices. As noted, approximately two-thirds of the reported shark catch in southern Africa from 2010 to 2012 was bycatch10. Unwanted bycatch harms sharks and fishers who must waste time removing the catch from fishing gear, sometimes at considerable personal risk.

This may include expanding the list of prohibited species, strengthening monitoring and enforcement systems, and efforts to reduce high mortality rates for discarded catch (e.g., skills training on how to release hooked sharks to minimise post-release mortality, education and awareness raising aimed improving handling and safe release of sharks caught as unwanted bycatch, especially threatened endemic species, such as the happy Eddie (Haploblepharus edwardsii, EN) and brown shyshark (Haploblepharus fuscus, VU)).

Illegal fisheries

Interventions are urgently needed to eradicate illegal gillnetting operations in estuaries and the open sea, recognising that this represents a threat to both legal fisheries and sharks as well as other species taken as bycatch by illegal gillnets9.

Regional cooperation

Given that many of South Africa’s shark species are highly mobile and spend only part of their annual life cycles in South African waters, there is also a need for regional collaboration with other countries (especially neighbouring countries, Mozambique and Namibia) and in marine areas beyond national jurisdiction to reduce threats to South Africa’s sharks beyond our waters. This is especially important for the 47 South African shark species listed as Critically Endangered or Endangered.

Monitoring

Science-based management to ensure sustainable fisheries for both target and bycatch species within an ecosystem approach to fisheries requires adequate data on the status and trends of relevant fish stocks. In South Africa, fisheries-independent surveys, including demersal trawl surveys and shore angling surveys, provide essential data for status assessments and should be continued or even expanded.

More sophisticated fisheries stock assessments designed to optimise harvest levels with respect to various management objectives require reliable time-series of catch and associated effort data. In South Africa, this information is currently only available for 10 species, and stock assessments have only been attempted for five species10.

While most of the required catch and effort data are self-reported, self-reporting is not always reliable and datasets can be significantly improved through fisheries observer programmes. It is recommended that the scientific observer programme is re-establshed in the demersal trawl fishery, observer coverage is improved in priority fisheries, and training provided in shark species identification and other relevant skills. Electronic monitoring systems have been tested by various countries and shown to be effective at monitoring catches in some fisheries and could enable expanded coverage at lower cost, but species identification will likely be challenging in the case of sharks. Fisheries observer programmes can also provide a valued source of employment for fisheries-dependent communities. In South Africa, electronic monitoring is being tested in the demersal shark longline fishery, with preliminary results showing promise9.

More data are also required to assess the impacts of recreational fisheries, as catches are not currently reported leading to significant gaps in our understanding of fishing pressure.

Monitoring of species-specific trade statistics would also help to pinpoint and address discrepancies between reported landings and exports, especially for fins destined for Hong Kong markets5, given that most shark products are exported.

Knowledge gaps

Scientific research is essential to improve our understanding of shark biology, ecology, and population status, for assessing the impact of human activities on sharks, and informing management2.

Much of the research on South African sharks has focused on the distribution, abundance and movement patterns of large, charismatic, non-harvested species, while fisheries research has focused primarily on the biology and life history of the larger targeted and marketable species or those caught in large numbers in research surveys10.

In addition to monitoring of population trends to inform science-based fisheries management, more information is needed on the distribution, habitat, and movement patterns of threatened species, especially identification of sites of particular importance for key life-cycle processes such as mating and feeding aggregations and nursery grounds. This information can then guide spatial management approaches, including identification of sites with critical habitat that are essential for shark conservation and recovery and may require special protection measures.

An understanding of key life-history parameters is also needed to identify those less well-studied species that are especially vulnerable to overfishing.

The two volumes of Species Profiles of South African Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras14,19 provide detailed species-specific comments on current and future importance of research for each species covered.

Approach

South African sharks have been assessed through the global IUCN Shark Specialist Group and most of these assessments were adopted for the South African Red List. National assessments were conducted for 33 non-endemic species through a process including two expert workshops and follow-up expert engagements. Species selection was based primarily on the list of shark species included in South Africa’s Second National Plan of Action for sharks (NPOA-Sharks II5) for which the proposed national assessment differed from the current global assessment, followed by consultation with national shark experts.

Two data sources are especially important for informing both national and global assessments of sharks occurring in South Africa: demersal trawl surveys along the west and south coasts and shore angling surveys in De Hoop MPA. These datasets provided the basis for quantitative analysis of population trends. Estimates of population change over three generation lengths were then used to assign species to the most likely IUCN Red List Category. The proposed status was then reviewed by species experts prior to confirmation.

The trend in species status over time was measured using the globally recognised indicator, the IUCN Red List Index of species (RLI)20. The RLI is calculated based on genuine changes in IUCN Red List categories over time. The RLI value ranges from 0 to 1. At a value of 1, all species are at low risk of extinction (Least Concern), while a value of 0 indicates that all species are extinct. The slope of the line indicates the rate at which species are becoming more threatened over time.

The RLI was calculated for all shark species in South African waters (n = 191), using national status assessments where available and global status assessments otherwise.

For further information on approach, see here.

Acknowledgements

Members of the IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group are sincerely thanked for their contributions to the nationally adjusted assessments under very tight time frames.

Recommended citation

Boyd, C., Sink, K.J., Atkins, S., Bennett, R., Cliff, G., Daly, R., Da Silva, C., Kerwath, S.E., Kock, A.A., Leslie, R., Singh, S., Van der Colff, D., Meissenheimer, K., Hendricks, S.E., Monyeki, M.S., & Raimondo, D.C. 2026. Sharks, rays and chimaeras. National Biodiversity Assessment 2025. South African National Biodiversity Institute. http://nba.sanbi.org.za/.