The 2025 National Biodiversity Assessment identified key marine ecosystems, species and benefits at risk, and knowledge gaps limiting the assessment. Priority actions to safeguard ocean life and livelihoods were co-developed in collaboration with knowledge holders and decision makers. Advancing these priority actions can help to improve the state of marine biodiversity and maintain its many benefits to South Africans.

Research progress and priorities

During the 2025 assessment of threat status and protection level of marine ecosystems and species, many research gaps that limit the assessment of marine biodiversity emerged. Knowledge gaps identified in the 2008 assessment1 were also revisited and progress against these were briefly evaluated to identify persistent knowledge gaps.

Persistent knowledge gaps and research priorities span foundational marine biodiversity research at the ecosystem, species and genetic level, to applied research for improving our understanding of the impacts of key pressures on ecological condition. New research priorities include the need for increased social science in the marine realm particularly to track progress in more equitable marine protection (ecosystem protection level page).

Foundational biodiversity research

There has been some progress with foundational biodiversity research at the species, genetic and ecosystem levels. Taxonomic and molecular research progress over the last few years includes progress made through the SAEON led SeaMap project (funded through the National Research Foundation’s Foundational Biodiversity Initiative) which provided new distribution records for marine invertebrates that are informing spatial biodiversity priorities.

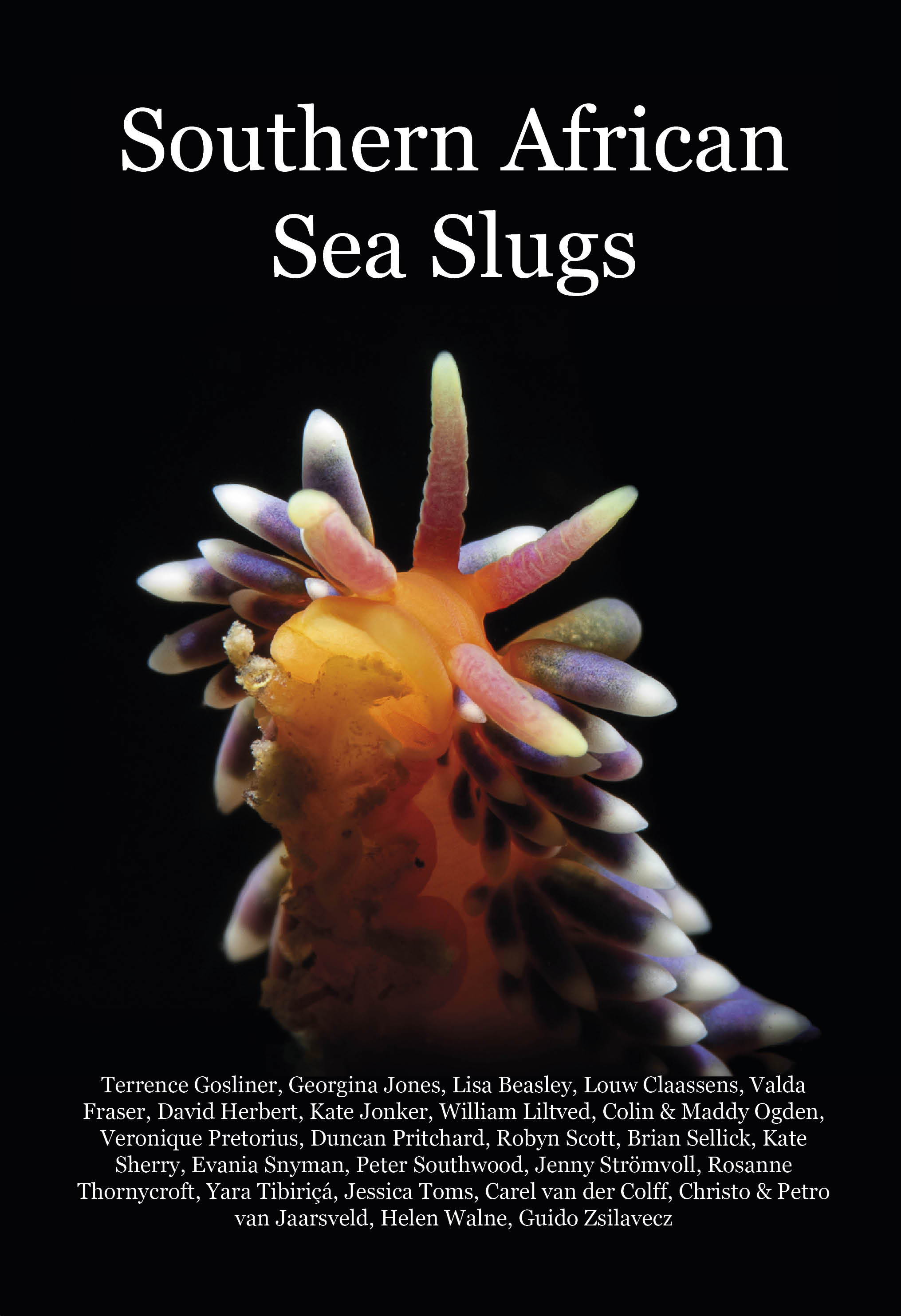

Citizen science is also supporting taxonomic research (Nudibranchs) although potential records far exceed taxonomic capacity and reference collections need investment to make the most of this approach. A reference image database is being advanced2 and there is a need to invest in digital taxonomy3. Progress in the application of machine learning in processing of seabed imagery is limited by taxonomic constraints with a need to undertake reference collections with in situ images and barcodes linked to taxonomic samples. Further systematic prioritization of invertebrate groups together with filling taxonomic knowledge gaps could improve our ability to conduct more Red List assessments for marine invertebrates4.

Some areas of progress in foundational biodiversity research for species include improved taxonomic knowledge on sea slugs (Box 1), sea cucumbers and azoozanthellate corals. Taxonomic descriptions of 170 southern African sea cucumbers species were published, representing 55 years of research, and calling for increased efforts to further build taxonomic capacity in southern Africa5. The state of knowledge of South African azooxanthellate coral species has been improved, with the total number of known species increased from 77 to 108, with 28 new species records, three new species and one new genus6.

A new field guide entitled Southern African Sea Slugs was published at the end of 2023 and represents a comprehensive update of our knowledge of the opisthobranch fauna. The most recent previous publication for this group was Nudibranchs of Southern Africa, which was published in 1987, covered 268 species. By 2023, a further 600 species had been observed with scuba divers playing a major role in documenting new records. The sheer range and diversity of species included in the guide are a testament to the astonishing biodiversity of the region and also to the diverse community of scientists, photographers, artists and citizen scientists who worked together to create the book. Thousands of field observations were collated to give the most accurate picture of species’ size, geographical and depth ranges and life histories known to date.

Gaps remain in systematic genetic barcoding efforts and genetic baselines for priority species. South Africa has made progress in adopting genetic indicators that are part of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework but marine taxa and particularly marine invertebrates are particularly neglected.

Foundational ecosystem knowledge has been improved and includes new and improved species distribution knowledge for informing a more data-driven national marine ecosystem map.

Other taxonomic research priorities include work on important marine ecosystem engineers (habitat forming animals including Vulnerable Marine Ecosystem Indicator taxa7), marine invertebrates that are sensitive to water quality changes and other indicator taxa. South Africa’s Marine Taxonomy Working group identified several national priorities to help address the critical shortfall in marine taxonomic research and capacity.

Research to validate and improve South Africa’s evolving national map of marine ecosystem types. Research effort beyond the shelf including slope, plateau, seamount and abyssal systems is particularly encouraged with a need to test the extent of differences between deep-sea ecosystem types in the Indian, Atlantic and Southern oceans.

Research to identify key drivers of marine biodiversity patterns and ecosystem processes from under researched geographic areas.

Integrated taxonomic research with a focus on validating species identification with in-situ imagery and genetic barcodes. This will enable increased application of increasing imagery to support foundational ecosystem research and monitoring. Taxonomic priorities are shown in Box 2.

Sustained research to support population genetic baselines and strategic long-term monitoring of species and populations in need of recovery. Priority taxa could include overexploited and threatened marine invertebrates (link to marine species page).

Research that advances the use of machine learning, artificial intelligence and data analytics for the analysis of big data and in support of the national marine ecosystem map.

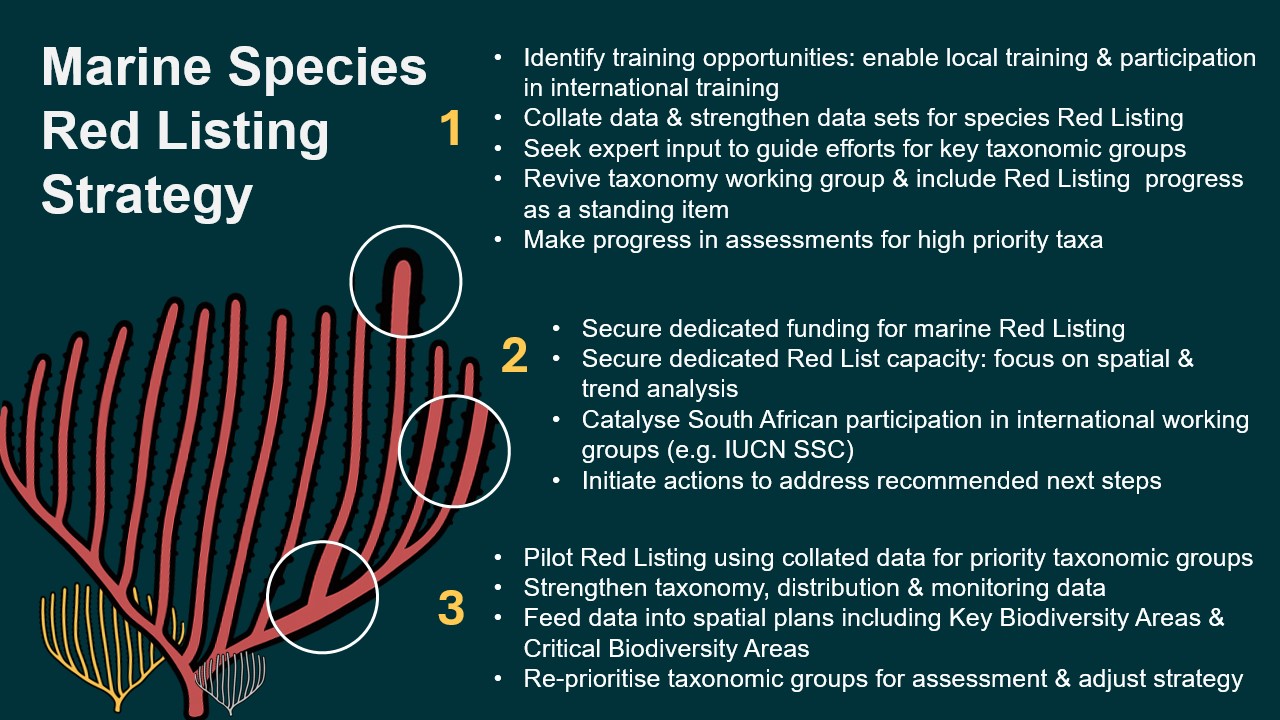

Ongoing challenges in assessing marine species, genetic biodiversity and ecosystems include the crises in taxonomy and a poor understanding of species distribution data. Innovative and integrated methods that can help address these gaps include imaging approaches, molecular methods, digital taxonomy, active and passive acoustics, citizen science and the strategic connection of biodiversity databases8. Progress in these complementary areas can increase our understanding of species distribution and feed into improved marine biodiversity assessments at all levels (genetic, species and ecosystems) and multiple scales. Foundational data gaps and capacity constraints limit the IUCN Red List assessment (extinction risk) of marine species. Although dedicated marine species red listing support has been recognised as a key requirement since 2018 (Sink et al. 2019 chapter 11 prev NBA), there has been no progress in securing resources or capacity to advance this work4.

Ensure taxonomic data is effectively collated, coordinated and managed through effective data management, integrated and accessible platforms that prioritise taxonomic data and by employing and developing well trained, permanent, networked data managers /systems administrators across institutions.

Communicate the value of taxonomic research, collections and collection management to mobilise increased and resources and capacity to address foundational marine biodiversity knowledge. Collections must be recognised as critical national assets that underpin biodiversity management.

Improve the accuracy of taxonomic components of biodiversity research, environmental impact assessment and natural resource management studies by facilitating, funding and promoting the involvement of taxonomists in such efforts and ensuring that the cost of their contribution is budgeted for in publicly funded projects (e.g. in port surveys, environmental impact studies and statements, fishery management assessments, etc.). Collection and lodgement of voucher specimens from such projects also requires funding support.

Increase job opportunities, research funding and provide direction for taxonomic centres to continue to describe, inventory and assess the marine biota of South Africa. Key taxonomic priorities include cnidarians, sponges, bryozoans, polychaetes, crustaceans, ascidians and elasmobranchs. These priorities were based on available expertise, extent of endemism, economic importance, components of sensitive seabed habitats, invasive potential, indicators of global change and critical knowledge gaps identified during this assessment.

Encourage and support efforts to enhance the development of modern taxonomic keys, digital and other guides, and other accessible taxonomic outreach products.

Enlist the support of the Department of Science and Innovation and Universities to promote the inclusion of taxonomy in undergraduate curricula and the teaching of taxonomy by appropriately trained educators.

Establish targeted PhD scholarships for students of taxonomy and mentoring programs to support early-career researchers to train with local and international taxonomists.

Support increased research, training and funding for the development of molecular genetic techniques in the taxonomy of marine organisms – including post-graduate training and developing incentives to partner with industry. South Africa must make further progress in integrated taxonomy.

Help organisations that use taxonomic outputs but do not themselves employ taxonomists to support these priorities. For example, Environmental Consultants and MPA management agencies can encourage taxonomists to assist in Environmental Impacts Assessments and MPA surveys and provide key specimens and funding where available to help build taxonomic knowledge.

Attract international experts to collaborate and develop South African capacity for priority groups.

Applied research to support species and ecosystem assessment and management

A national genetics monitoring framework is still lacking but genetic monitoring tools and indicators are available. There is a need to increase effort on marine taxa.

Little progress has been made on IUCN redlisting of marine species and no progress has been made in terms of evaluating species protection levels in the marine realm although research to evaluate potential increases in protection level of the African penguin is underway. Research is needed to comprehensively assess species taxon groups using the IUCN Red List criteria and improve current knowledge on the state and protection levels of South Africa’s marine species.

Progress has been made in evaluating the ecological, socio-economic and governance effectiveness of MPA’s but efforts to monitor and evaluate the in situ ecological and socio-economic benefits of MPAs can be strengthened (see ecosystem protection level page). Further research is required to effectively measure and report on equitable governance of marine conservation areas as per target 3 of the Global Biodiversity Framework.

There has been progress in research to support groundtruthing of marine ecological condition9–11. Challenges in measuring ecosystem condition and developing agreed thresholds of collapse for different ecosystem functional groups include capacity gaps, data and monitoring gaps and conceptual challenges with the need to apply a greater diversity of indicators to this end. Groundtruthing ecosystem types remains crucial for ongoing improvement of their descriptions and delineations. For example, the marine realm uses techniques such as remote operated vehicle surveys and seabed sampling (e.g. by grab samples, research trawls and sleds) to collect information on biotic components of ecosystem types; while abiotic data like bathymetry, water turbidity, productivity data and sediments also contribute to ecosystem classification. Progress in work to strengthen the classification and delineation of marine ecosystem types is detailed on the ecosystem types page.

Whilst progress has been made in the initiation of research to strengthen our understanding of underwater radiated noise, these efforts require further support over the long term so that the impacts of noise can be better understood and adequately accounted for in biodiversity assessment, spatial planning and management.

Progress has been made in the detection of microplastics and other emerging contaminants (including pharmaceuticals and pesticides)12–15, however the impacts of these are still poorly understood in a national context. Mapping these pressures would enable their use in biodiversity assessment and spatial biodiversity prioritisation.

Research to support IUCN Red List assessments of marine species. There is a need to increase the number of marine taxonomic groups that are comprehensively assessed using the IUCN Red List criteria.

Research and spatial analysis to measure protection levels of threatened marine species.

Research to ground-truth ecosystem condition is extended to other ecosystem functional groups (particularly in kelp forest, muddy, sandy and deep sea ecosystem types).

Research to develop conceptual models for ecosystem functional groups and develop thresholds of ecosystem collapse.

Science to support the development of more diverse indicators of ecosystem degradation and condition that can be used in ecosystem assessments.

Research to develop an accepted method to determine flow (fresh water and sediment requirements for estuarine and marine systems.

Research to develop indicators to track progress and improve equitable and effective ocean protection in South Africa (as per target 3 of the Global Biodiversity Framework).

Research to support the mapping and management of noise-sensitive species and ecosystems and improving understanding of impacts.

Research to better understanding the biodiversity and socio-economic impacts of pollution (including microplastics, pharmaceuticals, heavy metals and other emerging pollutants).

Biodiversity and people

There has been progress in identifying and mapping coastal ecological infrastructure16–18 and understanding the services that these provide to society. Although initial steps have been taken to build equivalent understanding for the deep-sea19, further research effort is required.

Research has been conducted on cultural connections to the ocean20 and advancing this research at more local scales through transdisciplinary methodologies can improve our national understanding of ocean tangible and intangible cultural heritage to support the recognition and safeguarding of cultural connections to marine biodiversity. Research on other socio-economic considerations can also be advanced so that ocean cultures and values, societal vulnerabilities and socio-economic considerations can be better accounted for in marine biodiversity spatial planning, prioritisation and management.

Participatory research has been advanced to understand and map the resource use patterns and priorities of small-scale fishers21 and further research effort is needed to expand this knowledge across the different geographies of South Africa.

Research to build knowledge on the ecosystem services in the deep sea and its role in supporting key production sectors, livelihoods, climate resilience and the economy.

Socio-ecological and human-dimension research, including inter-disciplinary research, to support spatial planning, prioritisation and management and resource management. The co-development of research questions with stakeholders and diverse research institutions is encouraged.

Further research to understand the cost and benefits of non-extractive utilization of marine species at different scales.

Further research to understand spatial resource use patterns and priorities of the small-scale fisheries sector to improve representation of this sector in spatial planning.

Priority actions for improving the state of marine biodiversity

Drawing from the key findings of NBA 2025, several priority actions were co-developed to improve the state of marine biodiversity in South Africa22–24. More than 80 individual actions were co-developed and classified into ten broad thematic areas with more detailed recommended steps and potential indicators of progress for each action. These are not comprehensive, prescriptive or time bound but include specific and measurable elements, where possible, to more easily track progress. Each of the 10 actions were linked to relevant Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) targets (Box 3) to easily inform ongoing policy processes. The marine assessment team will evaluate progress for these recommended steps in future assessments.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) is a global agreement under the Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD), which South Africa has formally committed to. The framework has four goals and 23 targets for protecting, conserving and restoring biodiversity. South Africa is in the process of domesticating the GBF targets and aligning its national strategies to achieve these ambitious targets.

Whilst aimed at improving biodiversity, the GBF framework elevates the importance of indigenous people and local communities, and seeks to recognise and enhance the role this important stakeholder group plays in protecting and managing biodiversity now and in the future. Further details are available in the 2030 targets.

Potential indicators of progress could include:

New or strengthened fora, collectives and platforms are established or revived through which government institutions can actively engage communities, civil society, industry and non-profit organisations with a focus on indigenous peoples, women and youth, heritage institutions, small-scale fishers, traditional leaders, traditional healers, and other traditional and local knowledge holders on matters related to ocean planning, management, development and decision-making. The Offshore Environment Forum could be re-convened with strengthened participation from shipping and heritage.

Indigenous knowledge working groups are established with co-developed guidelines and outputs that support the recognition and inclusion of indigenous knowledge in marine biodiversity assessment, planning and decision-making. Identify and establish mechanisms for integrating Indigenous knowledge into existing and new management plans, actions, and policies and other outputs and outcomes related to planning, management, and decision-making.

Indigenous knowledge is recognised and considered in marine biodiversity assessment, planning, policies, action plans and decisions alongside other knowledge forms. One way to support this is through the establishment of indigenous knowledge working groups and the co-development of guidelines to safeguard and support the recognition and inclusion of indigenous knowledge in a marine context.

National and local small-scale fisheries priority areas maps are developed and validated through processes that prioritise and actively involve indigenous people and small-scale fishing communities to represent the spatial interests of this vulnerable sector in national ocean planning and decision-making processes.

There is an increase in the number of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) with representative local stakeholder fora actively engaged in co-management. In 2025, very few of South Africa’s MPAs have active MPA fora, advisory groups or Protected Area Advisory Committees (PAACs).

There is financial and logistical support to enable meaningful participation of previously marginalised small-scale fishing coastal communities and knowledge holders in participatory processes and the formats, venue and language used support active participation.

*An institution’s social practice is the way in which it engages internal and external parties in doing its work - from research to planning and policy development to implementation - so that stakeholders co-create the outcome of the process. Given that this work always takes place in a constantly shifting context and is never the same, it requires a creative learning environment within institutions to flourish.

Potential indicators of progress could include:

The role and focus of marine inter-governmental and cross-sectoral working groups and task teams are reviewed with steps taken to clarify, simplify, streamline workstreams and enhance efficiency.

New or revived structures and processes to advance ecosystem-based management (including ecosystem-based fisheries management and better consideration of cumulative impacts in environmental impact assessments) are established with holistic recommendations co-developed and implemented for integrated management.

Improved policy alignment, communication and coordination between government departments and agencies responsible for fishing rights allocation, small-scale fisheries, ocean conservation and management.

Co-ordinated engagement and problem solving to address the persistent challenges facing small-scale fishers including issues related to permitting, rights allocation, MPAs and co-management.

There is progress in cross sectoral biodiversity prioritisation (working with sectors such as heritage, fisheries and tourism) to support implementation of integrated biodiversity-inclusive marine spatial planning.

Marine biodiversity priorities and key considerations for ecosystem based management are integrated in the environmental screening tool that supports environmental impact assessments.

Improved co-ordination facilitates an integrated approach that combines the management of flow, water quality and ecological and built infrastructure to secure vital freshwater flows to the marine realm.

An overarching framework for integrated shark management (considering fisheries, conservation, tourism and trade) is developed and its implementation is initiated. Progress could be measured in species level fisheries data, bycatch reduction in industrial fisheries, reduction of recreational fisheries pressure on sharks and rays, effective spatial protection, further reduction in the impacts of lethal shark control measures and strengthened cooperative analyses of the impact of trade.

Potential indicators of progress could include:

Cumulative effects of mining are considered in environmental impact assessments.

Other environmental management tools (such as Strategic Environmental Assessments and Environmental Management Frameworks) are harnessed to support more strategic mining decisions that can ensure that critical coastal and marine ecosystem services are maintained. In addition, increased resources to improve monitoring, compliance and enforcement can reduce illegal mining.

Critical Biodiversity Areas and Sea-Use guidelines are mainstreamed within key production sectors and included in screening tools used for Environmental Impact Assessments to guide infrastructure placement and development.

The impacts of underwater noise impacts are better accounted for in biodiversity assessments, Marine Spatial Planning, mining authorizations and protected area management.

Innovative finance tools in South Africa are piloted to demonstrate how industrial sectors can fund marine conservation restoration (e.g. blue bonds and mechanisms to enable the polluter pays principle).

The Ballast Water Act, which has been in Bill form since 2013, is promulgated by South Africa and implemented with the associated regulations and compliance systems.

New marine mainstreaming initiatives are developed and implemented to reduce pollution (including underwater noise), seabed and shore damage and impacts on threatened marine species. These could include scaled-up incentives for sustainable use and conservation through eco-certification and other mechanisms.

Industrial impacts in MPAs are reduced and conservation-area expansion efforts contribute to reduced conflict between sectors.

Potential indicators of progress could include:

A lead department is assigned to coordinate and ensure that flow requirements for fluvially dependent marine ecosystems and resources are determined and secured.

A method for determining flow requirements is officially accepted and adopted as a standard protocol.

Priority catchments are identified and communicated in the next version of the NBA, with progress in holistic catchment management to support improved quality and quantity of fresh water reaching the sea.

Marine flow requirements have been recognised in legislation and integrated into water resource management, coastal management and marine living resource management processes.

New collaborations and partnerships have been established between existing initiatives to catalyse better co-ordination and have greater impact with reducing the amount of pollution and litter reaching the sea.

Coastal sewerage infrastructure is upgraded and maintained to ensure sustainable sewage management that reduces contamination by bacteria, viruses, heavy metals, chemicals and improves coastal water quality.

Effective measures are developed and implemented to minimize solid waste, plastics, and microplastics entering the marine environment from rivers, stormwater outlets, outfalls and other sources.

Ecosystem condition and threat status of fluvially dependent marine ecosystems improves in the long term.

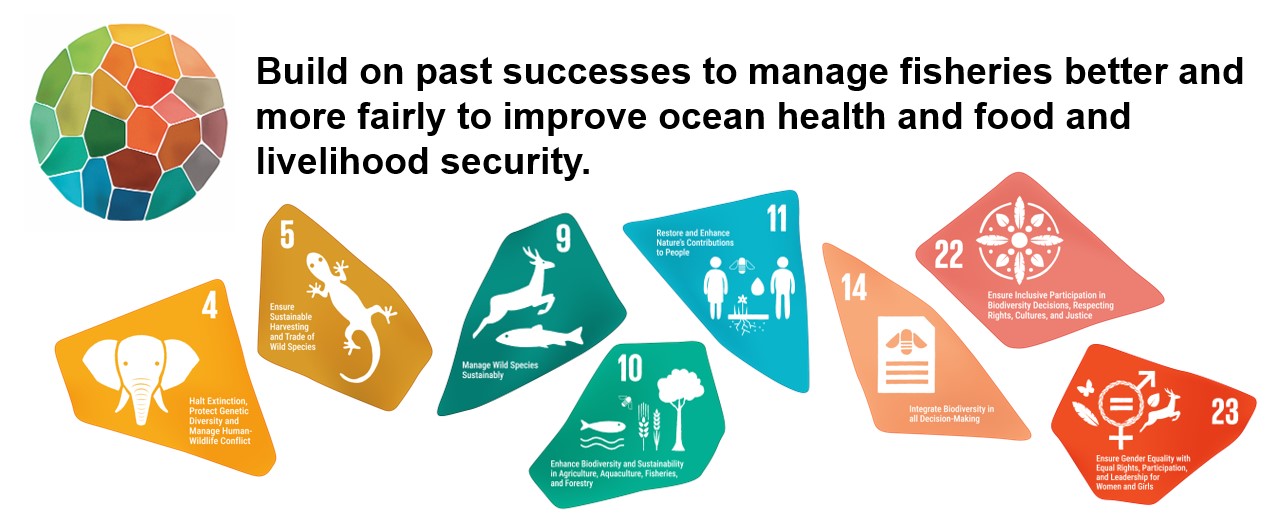

Potential indicators of progress could include:

Fisheries management plans for fishing sectors are developed to ensure ecological sustainability for long term economic sustainability. These should support resource (target species) sustainability, include bycatch and habitat management objectives (where applicable), address the human dimensions of fisheries, and include climate change considerations. Participatory approaches could help include fisher knowledge in these plans building on existing mechanisms for stakeholder inclusion in South African fisheries management.

A bycatch management strategy is developed and implemented to improve fisheries sustainability, reduce inter-sector conflict and support fair fisheries.

Ecological Risk Assessments are reviewed and key steps to avoid and mitigate ecosystem risks are identified with actions initiated to address risks.

Illegal harvesting of South African abalone (Haliotis midae) and West Coast rock lobster (Jasus lalandii) is reduced with evidence of resource recovery.

Traditional fishing practices have been respected and safeguarded from industrial maritime sectors (industrial fisheries impacts), through the prioritisation of such practices in MPA design and expansion.

Recreational fisheries management is reformed to improve fisheries sustainability and enable holistic management and equitable marine resource sharing across fishing sectors:

The Marine Living Resources Act is amended to facilitate rapid regulatory changes (size limit, bag limit, closed season, prohibited species) to ensure timely responses to critical marine resource issues.

A proportion of recreational angling license funding is secured for recreational fisheries monitoring, compliance, assessment and stakeholder engagement (through the establishment of a representative peak body) to ensure that these essential governance activities are sufficiently funded.

A transdisciplinary recreational fisheries monitoring strategy is co-developed to effectively address the lack of catch and effort data in the fishery, to improve the evidence for informed decision making and equitable marine resource sharing with the small-scale fishery sector.

A multifaceted (normative and instrumental) recreational fisheries compliance strategy is co-developed with stakeholders.

Levels of non-compliance are reduced due to outreach initiatives, implementation of compliance strategy, increased legitimacy of fisheries regulations and mainstreaming within the recreational fisheries sector.

Potential indicators of progress could include:

Organisations tasked with design, implementation and management of marine protected and conserved areas and fisheries management have capacity for social science research, reflective social practice, process facilitation and community development.

Clear and specific gazetted MPA objectives that encompass both biodiversity conservation, cultural heritage and socio-economic considerations are established through retrospective reviews for MPAs lacking clear purposes.

A formal definition, common understanding, and practical framework for “co-management” in an MPA-specific context is co-developed and harmonised with co-existing contexts (e.g., Fisheries).

New spatial management measures that have potential relevance for marine biodiversity conservation, cultural heritage protection or sustainable use (such as Special Management Areas, marine heritage sites and small-scale fishing zones) are piloted.

Innovative sustainable finance mechanisms to support long-term comprehensive operational funding for MPAs are tested.

There is increased capacity for collaborative monitoring, surveillance and compliance in and around MPAs with increased funding, new partnerships (including community collaborations) and innovative technology to support these efforts.

Offshore protection levels are improved, in particular for slope ecosystem types.

The spatial protection of threatened sharks and rays, seabreams and kobs (genus Argyrosomus) is improved, especially within vulnerable aggregation sites, nursery areas and bycatch hotspots.

Measures are implemented to reduce light pollution in protected and conserved areas.

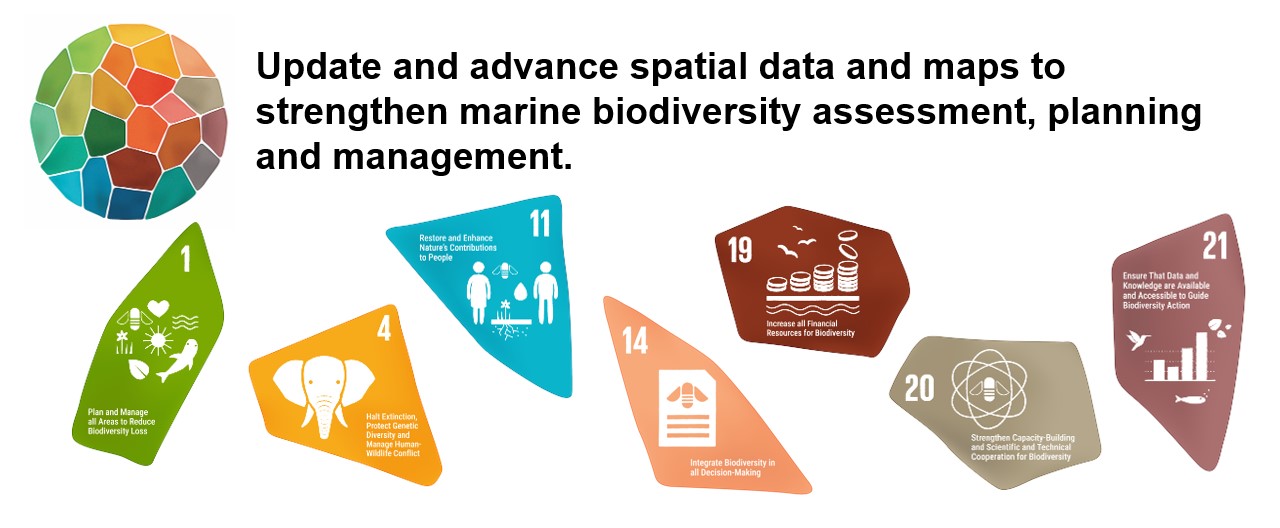

Potential indicators of progress could include:

An updated Critical Biodiversity Area map is produced including the many new spatial data sets leveraged for improved biodiversity planning since 2022.

Marine pressure layers are updated for improved biodiversity assessment and ocean decision making.

New inter-disciplinary data and knowledge products are developed for inclusion in marine spatial planning to support the recognition and safeguarding of cultural connections to marine biodiversity.

New knowledge products are developed to support the inclusion of climate mitigation, climate adaptation, and ecosystem services in ocean decision-making.

Noise-sensitive species and ecosystems are better included in biodiversity assessment and spatial prioritisations and planning.

Genetic data are included in spatial assessment and planning.

Dedicated resources and capacity to advance IUCN Red List assessments of marine species and ecosystems are secured.

Leverage funding and employment opportunities to enable young professionals to contribute to improved biodiversity assessment, planning and management in the marine realm.

A coordinated national marine biodiversity monitoring framework is developed.

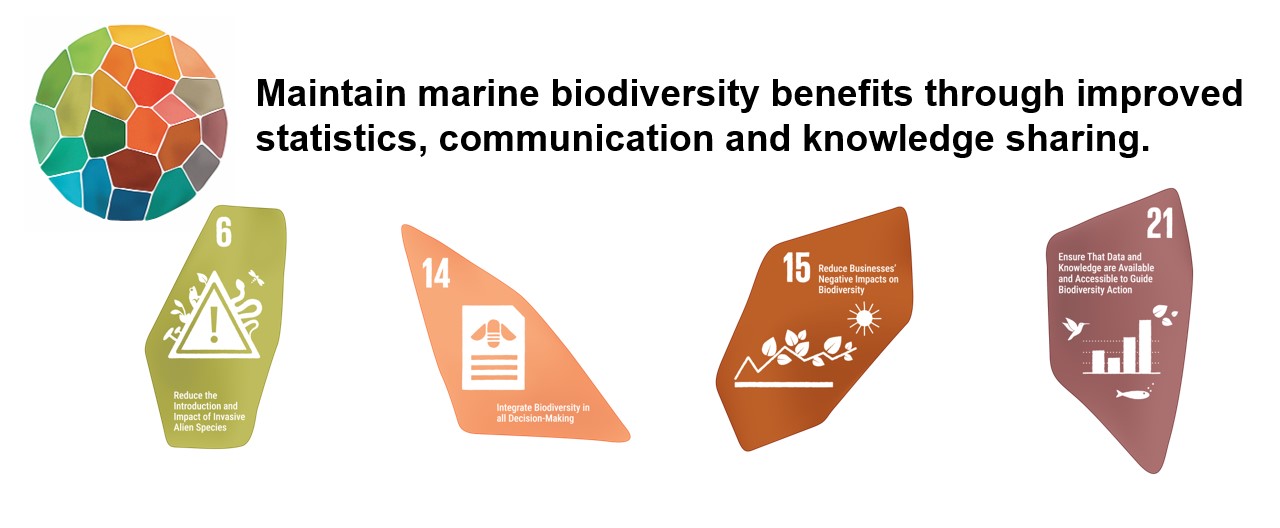

Potential indicators of progress could include:

New knowledge products are developed to support the consideration of marine biodiversity and ecosystem services in ocean decision-making.

Sufficient data managers, data scientists and spatial analysts, particularly early career ocean professionals are employed across the sector.

Researchers and key staff are trained in relevant data science tools, data standards and reproducible workflows.

Training of local youths in contributing to expanding knowledge through use of innovation and technology (citizen science).

Organisational data infrastructure, information technology and related policies and capacity enable effective database storage, curation and data sharing.

FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data principles and reproducible science workflows are prioritised.

Potential indicators of progress could include:

Marine sector needs are identified and communicated to Statistics South Africa to support data collection for new statistics that support effective communication of the value of marine biodiversity to the economy.

A first set of marine and coastal natural capital accounts is published and shared widely.

Innovative communication methods are employed to share marine biodiversity information widely and effectively ensuring all target audiences are reached. For example, the DiepRespek collaboration motivates for seabed protection and effective management of Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems. More content in local languages is recommended.

There are new opportunities and efforts to train, enable knowledge sharing and network communicators, scientists, and community champions.

New products are co-developed to make the case for the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries.

Communication efforts to reduce the risk of marine invasive species introductions are scaled up.

Economic growth is intrinsically linked to environmental benefits, and studies have shown that environmental degradation can have far reaching implications for economic activity and human health25. The System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA) Central Framework26 was adopted in 2012 as the international standard for developing environmental economic accounts that organises and presents statistics on the environment and its relationship with the economy.

Natural Capital Accounting (NCA), developed under the SEEA Central Framework, is an approach to quantify the value of natural resources and ecosystem services to the wealth of a country by allowing for the inclusion of environmental assets and their associated ecosystem services provided to the economy27–29.

Through the application of NCA in the marine and coastal realm, the value and contribution of marine and coastal ecosystems can be communicated in direct terms that link to the current System of National Accounts, illustrating the linkages and dependencies that exist between existing and future economic activities. For example, by linking the results of the NBA to maps of marine and coastal Ecological Infrastructure, NCA accounts can be developed to valuate and communicate the benefits from functional biodiversity in the availability and delivery of ecosystem services such as climate change mitigations, adaptation and resilience.

Potential indicators of progress could include:

Climate smart biodiversity planning is advanced, drawing from local knowledge, increasing research progress (including genetic considerations to preserve adaptive potential of species) and international lessons. In the long term, all marine sector plans consider climate change to advance climate smart marine spatial planning.

Restoration and protection of climate-buffering ecosystems is advanced, including both blue carbon vegetated habitats and biogenic carbonate systems (e.g., shellfish and coralline habitats).

Setback lines have been implemented in all coastal provinces to keep the littoral active zone intact. This will secure a zone within which shores can realign further inland in response to sea-level rise without being trapped and lost to coastal squeeze.

National monitoring and mapping of coastal and marine climate stressors (temperature anomalies, coastal acidification (pH), hypoxia, and coastal erosion) and biotic responses (harmful algal blooms, fish kills, coral bleaching, range shifts) is increased.

Spatial climate change data and predictions are included into the assessment of ecosystem threat status and other relevant risk assessments.

Local and indigenous knowledge is used in area and context specific climate adaptation plans including efforts to support adaptive management for vulnerable fishery sectors and fishers.

Coastal/beach access points are maintained to limit trampling and degradation of foredunes to enhance coastal protection against heightened wave energy during large storms. In addition, signage and public awareness are increased about the need to keep off foredunes to avoid trampling and degradation of this particularly sensitive zone to maximize coastal protection services and benefits.

There is formal integration of climate considerations into fisheries policy and legislation.

Existing or new communities of practice support inclusive integrated climate adaptation for marine and coastal ecosystems, fisheries and people.

Priority areas for safeguarding biodiversity

South Africa’s biodiversity is not evenly distributed across the seascape and when this is combined with limited resources for action, spatial prioritisation becomes essential. An important feature of South Africa’s biodiversity-related action to the pressures on biodiversity has been spatial planning to identify priority areas in the seascape for intervention. The NBA provides an initial portfolio of spatial priorities by highlighting the location of the most threatened ecosystems and species and by intersecting the results of ecosystem threat status and protection level. However, it is not only threatened biodiversity that needs attention; often there are strategic gains to be made from focusing on areas that are still in good ecological condition and where there are relatively easy opportunities for protection or effective management.

To learn more about biodiversity mapping, see SANBI’s guide on mapping biodiversity priorities and the IUCN’s course on Introduction to Mapping Biodiversity Priorities.

Critical Biodiversity Areas (CBAs)

SANBI, in collaboration with its partners, identifies Critical Biodiversity Areas (CBAs) across all realms. CBA mapping is achieved through the application of systematic conservation planning to identify areas that are in a natural/near-natural state that represent opportunities where biodiversity management action can be most impactful. CBA Maps are the biodiversity sector’s input into decisions on appropriate land and sea uses to safeguard a sufficient, representative sample of biodiversity that can persist into the future, in support of sustainable economic development and to meet international environmental commitments. Spatial biodiversity priority areas to protect, restore and recover marine ecosystems and species have been identified, and are being improved with increased stakeholder dialogue, collaboration, and technical innovation.

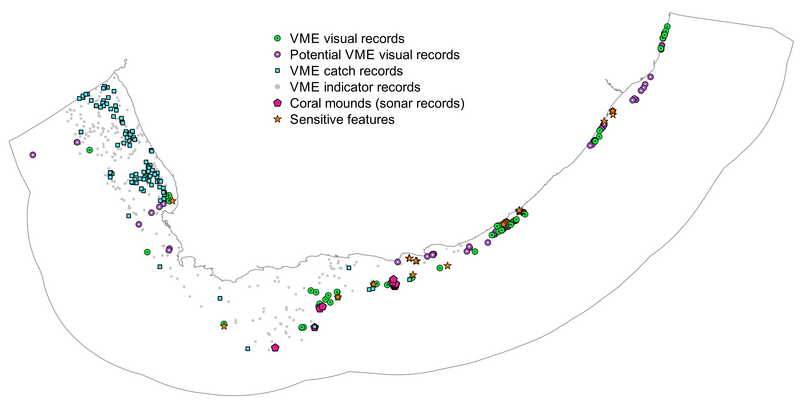

Since 2022, the number of spatial data layers that can inform national coastal and marine spatial biodiversity planning in South Africa has tripled. These include new species records for invertebrates and fish, updated Vulnerable Marine Ecosystem distribution data7 (Figure 2), new data for sharks, rays and chimaeras30, maps of Culturally Significant Areas20 and new data layers to improve climate resilience and connectivity in spatial planning. Work is underway to update the CBA Map in 2026.

Other Priority Areas

In the marine realm, South Africa also has a network of Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (EBSAs) that have been revised and resubmitted to the CBD. Initially, EBSAs were conceptualised to be a tool by which MPAs might be identified and established in the high seas; however, their value within national jurisdiction, and for helping countries to achieve their Aichi targets, soon became apparent. Through a series of regional workshops, EBSAs were identified by evaluating sites against seven criteria, and were delineated within country Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), in the high seas, and in transboundary (country-country, or country-high seas) areas. EBSAs in South Africa draw from systematic biodiversity plans and align with priorities developed as part of the National Coastal and Marine Spatial Biodiversity Plan.

Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) are an additional category of priority areas that represent the most important sites for global biodiversity conservation. They are identified using globally standardised criteria with thresholds established by the IUCN31. KBAs are site-based and are delineated with practical, manageable boundaries. The process to identify areas that meet KBA criteria is a separate process to delineating KBA boundaries. There has been little effort to map marine KBAs in South Africa to date but expanding biodiversity data puts South Africa in an excellent position to pilot marine KBAs across the country.

Approach

Knowledge gaps

Knowledge gaps and research priorities were identified throughout the NBA 2025, but also through a systematic review of progress against research priorities identified in the NBA 2018.

Priority actions

Drawing from the key findings of this assessment, more than 80 priority actions were co-developed to improve the condition of marine ecosystems and species, and to safeguard the many benefits they provide. To inform these actions, a series of science–policy-society engagements were held, bringing together researchers, decision-makers, civil society and knowledge holders (with a particular focus on coastal communities) to review research evidence and jointly co-develop recommendations to address key findings, identified risks and key pressures on South Africa’s marine biodiversity22–24. From the more than 80 specific actions, a set of 10 overarching priority actions were distilled with recommended indicators of progress that point to a range of sub-actions which if implemented could improve the state of marine biodiversity in South Africa.

Priority areas

South Africa has several established spatial prioritisation tools for informing the work of the biodiversity sector. These tools provide a comprehensive set of biodiversity priority areas that collectively meet biodiversity targets for ecosystems, species and ecological processes. Increasingly, critical ecological infrastructure assets are also included in this set of biodiversity priority areas and KBAs are a further set of global priority areas. Maps of biodiversity priority areas directly support the implementation of the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP).

In the terrestrial realm, Maps of CBAs and Ecological Support Areas (ESAs), presented together and referred to collectively as CBA maps, are produced by all provincial conservation authorities, marine planners and some metropolitan municipalities and are based on the principles of systematic biodiversity planning. They are a form of strategic planning for the natural environment, identifying a set of geographic areas that provide a spatial plan for ecological sustainability at the landscape and seascape scale. A CBA Map comprises five map categories: Protected Areas, CBAs, ESAs, Other Natural Areas and areas where there is No Natural habitat Remaining. Guidelines published by SANBI32 encourage consistency between the CBAs prepared by different agencies.

Protected areas, CBAs and ESAs together form a network of natural and semi-natural areas that enable ecologically functional seascapes and landscapes in the long term, designed to be spatially efficient and to avoid conflict with non-compatible land and ocean uses wherever possible. CBAs should be kept in a natural or near natural state to support ecological sustainability of the landscape and seascape. ESAs do not need to be entirely natural, but should be kept at least semi-natural so that they retain their ecological processes. These natural and semi-natural areas can co-exist in a matrix of multiple uses, including fisheries, aquaculture, mining, ports and others.

Land-based CBA Maps have been produced for over a decade, while the first map of CBAs and ESAs for the coast and ocean was completed in 20191. Since 2019, data collation and analyses have improved with the last published version of the CBA map produced in 2022 and further work underway to update the CBA map in 2026.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the more than 123 individuals who actively participated in the three engagements held to co-develop priority actions for improved Ecosystem Based Management in South Africa. In addition, SANBI appreciates further inputs from the SeaPeople collective, staff from DFFE Oceans and Coasts and Fisheries Branches, SANParks and provincial conservation entities. We acknowledge Sven Kerwath for his contributions in shaping selected priority actions. We also thank Merle Sowman for sharing insights on coastal and marine mining and Sarah Wilkinson for providing important perspectives on offshore industry activities and opportunities to strengthen offshore biodiversity management. Jess da Silva is thanked for her insights on genetic research priorities and key actions to maintain genetic biodiversity in the marine realm.

We acknowledge the National Research Foundation particularly projects funded through the Foundational Biodiversity Information Program (FBIP) and the African Coelacanth Ecosystem Program (ACEP). These include the SAEON led SeaMap project (Grant number 138572), Deep Connections (Grant number 129216), Agulhas Bank Connections (Grant number 129213) and Sound Seas projects (Ref number ACEP23040790163). This work was supported through international projects funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant Agreement No. 862428 (Mission Atlantic project) and 818123 (iAtlantic project), the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH for the MeerWissen CoastWise project, and the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) through the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), Grant ref: NE/S008950/1, for the One Ocean Hub project.

Key publications

Rylands S, et. al. 2025. Co-developing Management and Policy Actions in Support of Improved Marine Biodiversity in South Africa. Science to Policy Workshop Report and Draft Priority Actions for the 2025 National Biodiversity Assessment. Cape Town, South Africa. 22 pp.

Sink KJ, et. al. 2019. Chapter 11: Key findings, priority actions and knowledge gaps. In: Sink KJ, van der Bank MG, Majiedt PA, Harris LR, Atkinson LJ, Kirkman SP, Karenyi N (eds). 2019. South African National Biodiversity Assessment 2018 Technical Report Volume 4: Marine Realm. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. South Africa. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12143/6372

Sink K, et. al. 2023. Advancing Marine Ecosystem Based Management at the Science Policy Society Interface. A report from a science-policy workshop, Kirstenbosch, August 2023. 26pp.

Subramoney A-C, et. al. 2024. Planning for Marine Invertebrate Species Red Listing in South Africa. November 2024. SANBI, Cape Town. 41pp.

van der Bank MG, et. al. 2025. SeaPeople: Building trust and relationships for improved participatory planning, protection, and management in South Africa’s marine environment. May 2025 Workshop Report, SANBI, Cape Town.

Recommended citation

Sink, K.J., Van der Bank, M.G., Majiedt, P., Currie, J.C., Dunga, L.V., Farthing, M.W., Kirkman, S.P., Atkinson, L.J., Porri, F., Kock, A.A., Shibe, S.S., Mwicigi, J., Smith, K., Malatji, M., Karenyi, N., Franken, M., Fairweather, T.P., Henriques, R., Oosthuizen, A., Mzimela, N.Z., Besseling, N.A., Rylands, S., Layne, T., Oliver, J., Adams, L.A., Van Niekerk, L., & Harris, L.R. 2025. Knowledge gaps, priority actions and priority areas: Marine realm. National Biodiversity Assessment 2025. South African National Biodiversity Institute. http://nba.sanbi.org.za/.

References

1. Sink, K.J. et al. 2019.

Chapter 11: Key findings, priority actions and knowledge gaps. In Sink, K.J. et al. (eds), South African National Biodiversity Institute. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12143/6372, Pretoria.

2. Adams, L. et al. 2024. Advancing the Southern African Marine Biodiversity Reference Image Collection. Cape Town, South Africa.

4. Subramoney, A.-C. et al. 2024. Planning for marine invertebrate species red listing in South Africa. Cape Town, South Africa.

5. Thandar, A. 2022. A taxonomic monograph of the sea cucumbers of southern Africa (Echinodermata: Holothuroidea). South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, South Africa.

6. Filander, Z.N. et al. 2021. Azooxanthellate

Scleractinia (Cnidaria, Anthozoa) from South Africa.

ZooKeys 1066: 1–198.

https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.1066.69697

7. Franken, M. 2025. A systematic approach to the identification, mapping and spatial prioritisation of Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems in South Africa.

8. Rogers, A.D. et al. 2022. Discovering marine biodiversity in the 21st century. : 23–115. Elsevier.

https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.amb.2022.09.002

9. Smit, K.P. et al. 2023. Identifying suitable indicators to measure ecological condition of rocky reef ecosystems in

South Africa.

Ecological Indicators 154: 110696.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110696

10. Smit, K.P. et al. 2024. Groundtruthing cumulative impact assessments with biodiversity data: Testing indicators and methods for marine ecosystem condition assessments in South Africa.

Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 34: e4096.

https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.4096

11. Smit, K.P. et al. 2026. Depth and habitat drive spatial patterns in fish functional diversity: A trait-based assessment across

South Africa and southern Mozambique.

Marine Environmental Research 213: 107620.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2025.107620

12. Porter, S.N. et al. 2018. Accumulation of organochlorine pesticides in reef organisms from marginal coral reefs in

South Africa and links with coastal groundwater.

Marine Pollution Bulletin 137: 295–305.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.10.028

13. Sparks, C. & S. Immelman. 2020. Microplastics in offshore fish from the

Agulhas Bank, South Africa.

Marine Pollution Bulletin 156: 111216.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111216

14. Ojemaye, C.Y. & L. Petrik. 2022. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the marine environment around

False Bay, Cape Town, South Africa: Occurrence and risk

-assessment study.

Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 41: 614–634.

https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5053

16. Perschke, M.J. et al. 2023. Ecological Infrastructure as a framework for mapping ecosystem services for place-based conservation and management.

Journal for Nature Conservation 73: 126389.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2023.126389

17. Perschke, M.J. et al. 2023. Using ecological infrastructure to comprehensively map ecosystem service demand, flow and capacity for spatial assessment and planning.

Ecosystem Services 62: 101536.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2023.101536

18. Perschke, M.J. et al. 2024. Systematic conservation planning for people and nature: Biodiversity, ecosystem services, and equitable benefit sharing.

Ecosystem Services 68: 101637.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2024.101637

19. La Bianca, G. et al. 2023. A standardised ecosystem services framework for the deep sea.

Frontiers in Marine Science 10: 1176230.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1176230

20. Dunga, L.V. et al. 2025. Piloting a culturally significant areas framework for spatial planning and management in the coastal environment of

South Africa.

Marine Policy 180: 106807.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2025.106807

22. Sink, K. et al. 2023. Advancing Marine Ecosystem Based Management at the Science Policy Society Interface. Cape Town, South Africa.

23. Rylands, S. et al. 2025. Co-developing Management and Policy Actions in Support of Improved Marine Biodiversity in South Africa. Cape Town, South Africa.

24. Van der Bank, M. et al. 2025. SeaPeople: Building trust and relationships for improved participatory planning, protection, and management in South Africa’s marine environment. May 2025 workshop report. SANBI, Cape Town.

25. Acheampong, A.O. & E.E.O. Opoku. 2023. Environmental degradation and economic growth: Investigating linkages and potential pathways.

Energy Economics 123: 106734.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2023.106734

26. United Nations et al. 2014. System of environmental economic accounting 2012 - central framework. UN, EC, FAO, IMF, OECD; the World Bank, New York.

27. Costanza, R. et al. 2011. Valuing ecological systems and services. F1000 Biology Reports 3:

28. Costanza, R. et al. 1997. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital.

Nature 387: 253–260.

https://doi.org/10.1038/387253a0

29. Stebbings, E. et al. 2021. Accounting for benefits from natural capital: Applying a novel composite indicator framework to the marine environment.

Ecosystem Services 50: 101308.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2021.101308

30. Faure-Beaulieu, N. et al. 2023. A systematic conservation plan identifying critical areas for improved chondrichthyan protection in

South Africa.

Biological Conservation 284: 110163.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.110163

31. SANBI & UNEP-WCMC. 2024. Mapping biodiversity priorities: A practical approach to spatial biodiversity assessment and prioritisation to inform national policy, planning, decisions and action. Pretoria, South Africa.

32. SANBI. 2017. Technical guidelines for CBA maps: Guidelines for developing a map of critical biodiversity areas and ecological support areas using systematic biodiversity planning. First edition (beta version). Pretoria, South Africa.

Enhance meaningful participation and influence in decision-making for ocean planning, assessment and management to support a whole-of-society approach for effective ocean governance. Participation should extend beyond legislative requirements and advance towards good practice in participatory approaches that enable meaningful involvement of civil society, indigenous people and local communities. This can be achieved through robust inter-disciplinary approaches, inclusive stakeholder dialogue, strengthened capacity and social practice* across institutions, and through innovations in community and industry partnerships. Key messages

Enhance meaningful participation and influence in decision-making for ocean planning, assessment and management to support a whole-of-society approach for effective ocean governance. Participation should extend beyond legislative requirements and advance towards good practice in participatory approaches that enable meaningful involvement of civil society, indigenous people and local communities. This can be achieved through robust inter-disciplinary approaches, inclusive stakeholder dialogue, strengthened capacity and social practice* across institutions, and through innovations in community and industry partnerships. Key messages

Simplify, strengthen and co-ordinate institutional and sectoral arrangements, relationships and frameworks to enable a whole-of government approach for effective and efficient ocean planning and governance. This can be advanced through improved coordination, clear roles and responsibilities and more integrated spatial planning and ecosystem-based management. Improved co-ordination across sectors will also benefit coastal and marine climate adaptation. Key messages

Simplify, strengthen and co-ordinate institutional and sectoral arrangements, relationships and frameworks to enable a whole-of government approach for effective and efficient ocean planning and governance. This can be advanced through improved coordination, clear roles and responsibilities and more integrated spatial planning and ecosystem-based management. Improved co-ordination across sectors will also benefit coastal and marine climate adaptation. Key messages

Avoid, reduce and manage industrial impacts from maritime sectors through strategic mainstreaming within key production sectors, effective Marine Spatial Planning, strengthened mitigation and restoration and increased incentives. Key messages

Avoid, reduce and manage industrial impacts from maritime sectors through strategic mainstreaming within key production sectors, effective Marine Spatial Planning, strengthened mitigation and restoration and increased incentives. Key messages

South Africa needs to ensure that sufficient fresh water is allocated and received by the marine realm and that water quality is improved to maintain benefits for coastal ecosystems, species and people. Key messages

South Africa needs to ensure that sufficient fresh water is allocated and received by the marine realm and that water quality is improved to maintain benefits for coastal ecosystems, species and people. Key messages

Strengthen ecosystem-based fisheries management through periodic reviews and updates to ecological risk assessments, development and implementation of effective fisheries management plans, and increased biodiversity mainstreaming in fisheries. Key messages

Strengthen ecosystem-based fisheries management through periodic reviews and updates to ecological risk assessments, development and implementation of effective fisheries management plans, and increased biodiversity mainstreaming in fisheries. Key messages

Improve marine protection through more diverse and inclusive conservation models, inter-disciplinary approaches, improved social process and innovative finance, progress in co-management, restorative action and steps to address critical capacity shortfalls. Co-ordinated efforts to address persistent barriers to effective protection must be overcome and key lessons learnt should be applied in future expansion efforts. Key messages

Improve marine protection through more diverse and inclusive conservation models, inter-disciplinary approaches, improved social process and innovative finance, progress in co-management, restorative action and steps to address critical capacity shortfalls. Co-ordinated efforts to address persistent barriers to effective protection must be overcome and key lessons learnt should be applied in future expansion efforts. Key messages  Update key spatial layers and develop new maps and capacity to support improved species and ecosystem assessment, spatial prioritisation, and biodiversity inclusive spatial planning and management in the marine realm. Key messages

Update key spatial layers and develop new maps and capacity to support improved species and ecosystem assessment, spatial prioritisation, and biodiversity inclusive spatial planning and management in the marine realm. Key messages  Invest in data science capacity and infrastructure to ensure effective and reproducible data pipelines that integrate and update strategic analyses in a transparent way to support informed ocean decision-making. Strengthened capacity and infrastructure is needed for all organisations tasked with mapping, assessing, monitoring, and providing indicators and data products that inform management of marine biodiversity, fisheries and the ocean. This will require substantial investment. Key message

Invest in data science capacity and infrastructure to ensure effective and reproducible data pipelines that integrate and update strategic analyses in a transparent way to support informed ocean decision-making. Strengthened capacity and infrastructure is needed for all organisations tasked with mapping, assessing, monitoring, and providing indicators and data products that inform management of marine biodiversity, fisheries and the ocean. This will require substantial investment. Key message  Diversify and improve the communication of marine biodiversity (values and benefits, risks, opportunities and usage), and mainstream biodiversity into key production sectors. This evidence will enable better understanding of the value of marine biodiversity and its contribution to society and the economy. The role of intact biodiversity in supporting food production, the biodiversity economy and climate resilience can be better communicated to support the maintenance of biodiversity benefits. Key messages

Diversify and improve the communication of marine biodiversity (values and benefits, risks, opportunities and usage), and mainstream biodiversity into key production sectors. This evidence will enable better understanding of the value of marine biodiversity and its contribution to society and the economy. The role of intact biodiversity in supporting food production, the biodiversity economy and climate resilience can be better communicated to support the maintenance of biodiversity benefits. Key messages  South Africa needs to invest in the multiple opportunities for scaling up integrated climate action through inclusive choices that promote resilience, and prioritise risk reduction, equity and justice. Protection and restoration of healthy coastal ecosystems increases climate resilience and maintaining genetic diversity enables adaptation including for important food species. Increased and co-ordinated climate science is needed in the marine realm. Many relevant recommendations to support climate adaptation can be found in South Africa’s Climate Change Coastal Adaptation Response Plan (DFFE 2025) and international reports (such as Cooley et al. 2022) with local recommendations on climate adaptation for fisheries also published (Hyder et al. 2024). Key messages

South Africa needs to invest in the multiple opportunities for scaling up integrated climate action through inclusive choices that promote resilience, and prioritise risk reduction, equity and justice. Protection and restoration of healthy coastal ecosystems increases climate resilience and maintaining genetic diversity enables adaptation including for important food species. Increased and co-ordinated climate science is needed in the marine realm. Many relevant recommendations to support climate adaptation can be found in South Africa’s Climate Change Coastal Adaptation Response Plan (DFFE 2025) and international reports (such as Cooley et al. 2022) with local recommendations on climate adaptation for fisheries also published (Hyder et al. 2024). Key messages