Freshwater ecosystems – rivers and inland wetlands – face a multitude of pressures, including pollution from numerous sources, infrastructure development, and changes in land use. Their ecological functioning is particularly sensitive to changes in hydrology and water quality. Habitat loss and fragmentation, climate change, pollution, and invasive species persist as key direct drivers of biodiversity loss and freshwater ecosystem degradation, and do not appear to be abating since NBA 2018. Addressing these pervasive pressures is an essential component of conservation and management of these vital ecosystems.

Hydrological modification

Inappropriate abstraction and damming severely alter natural flow regimes and seasonality, frequently leading to ecosystem type change, such as a change from seasonal to permanently inundated wetland or regular to intermittent flowing river. This is leads to loss in connectivity, impacting the dispersal of migratory species, and competing demands on water.

Habitat degradation and loss

The conversion and fragmentation of rivers and wetlands, such as by agriculture, urban development, and mining, can lead to loss of ecosystem structure, erosion and inappropriate fire regimes. Both the suppression of fires and planned burning practices for grazing result in changes to the natural fire regimes and subsequently the species composition of vegetation associated with rivers and inland wetlands in the landscape. Suppression of fire in the Fynbos biome, for example, has led to the densification of vegetation and decline in habitat.

Pollution

Water pollution is a major cause of the decline in freshwater species, particularly freshwater fishes. A combination of sediment, nutrient, chemical and thermal water pollution cumulatively impact the biodiversity and functioning of river and inland wetland ecosystem types and their associated freshwater species. Pollution (such as poorly or untreated wastewater effluent from industries and wastewater treatment works, mining waste, acid mine drainage and agricultural return flows) significantly increases nutrients, metals, pesticides and other toxic compound loads; and can also change the natural temperature ranges and turbulence of aquatic environments. Furthermore, pharmaceuticals and micro-plastics are emerging contaminants that act as endocrine disruptors, impacting the productivity of aquatic species, and are of grave concern. Water pollution has dire, long-lasting consequences for aquatic organisms and hence ecosystems function. The Olifants River, which flows through the Kruger National Park, is a prime example of a river at the receiving end of a heavily utilised and degraded landscape. The impact of pollutants entering the river system have led to the demise of Endangered species such as the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus), attributed to pansteatitis, as well as the mortality of several fish species in Loskop Dam. A decline in piscivorous bird species has also been observed, including Pel’s fishing owl (Scotopelia peli).

Wetlands are at the front line of wastewater impacts given their location at the interface between the terrestrial and aquatic environments, especially in South Africa, with its generally poor performance of wastewater treatment works and declining state of catchment water quality. In the most recent national assessment, 68% of wastewater treatment works were identified as at high or critical risk of discharging partially treated or untreated water into the environment.

When using wetlands to enhance catchment water quality, the impacts on ecosystem services may be considerable. The use of wetlands to enhance water quality in polluted catchments has been well demonstrated, however a narrow focus on water quality objectives will likely lead to failure to account more broadly for the impacts on wetland ecological health, ecosystem services supply and ultimately human wellbeing.

Most ecosystem services provided by wetlands are negatively affected by wastewater inputs, except for rare instances where they are enhanced. One example of the latter is where nutrient-enriched wastewater promotes increased vegetation growth, which in turn increases the sediment carbon store in the wetland. Another example is when the prolonged hydroperiod and nutrient enrichment caused by the wastewater inputs may potentially enhance conditions for certain bird species, as occurred for the lesser flamingo (Phoeniconaias minor) at Kamfers Dam. These instances often occur in arid environments, such as the western parts of South Africa.

The vulnerability of wetlands to wastewater impacts depends on: (1) wetland type; (2) the wastewater inputs; and (3) other uses of the wetland. An inward draining (i.e. endorheic) wetland is inherently vulnerable as it has no outflow through which pollutants can be flushed from the system. High wastewater discharge with high loads of pathogenic bacteria impacts greatly on human wellbeing when use involves direct contact with the water (e.g. when used for conducting baptisms). If use of the wetland involves no direct contact with the water (e.g. as might be the case when observing water birds from a bird hide), the impacts in terms of human use would likely be less severe. Given the potential impacts and range in vulnerabilities, it is useful to distinguish between wetland areas and contexts that are most vulnerable to water quality impacts, and for which use should be kept to a minimum; and less vulnerable wetlands, which could potentially be designated as hard-working wetlands.

The pollutant assimilation capacity of wetlands is finite, and overloading a wetland will result in severe consequences for the wetland and downstream water users. Sustained point-source pollution into a wetland can overwhelm a wetland’s assimilative capacity, severely compromising its capacity to deal with non-point sources of pollution. In some cases where the initial effect of wastewater is positive, beyond a certain threshold its effect can dramatically shift to become negative, e.g. as occurred in the Kamfers Dam in 2011 when the sewage works was malfunctioning and many flamingos contracted avian pox virus through biting flies proliferating in the highly nutrient-enriched waters of the pan and which continues to recur1,2.

Long-term accumulation of pollutants in the sediments of wetlands pose a risk should the wetland sediments dry out or their biogeochemistry change. If a considerable amount of metals or other pollutants have accumulated over many decades under prolonged saturation in a wetland’s sediments, much of this can be released on drying out of the wetland3,4. The wetland may rapidly ’flip’ from being a major sink for metals and other pollutants to becoming a major source.

Climate change

Changes in climate, particularly rise in temperature and changes to the amount, intensity and season of precipitation, are expected to exacerbate the impacts of current pressures on inland aquatic ecosystems. Global temperatures have increased by almost 1 °C over the past 50 years and could increase another 1–2° C by 2050. Increasing temperature will impact the hydrological cycle, and consequently the functioning of rivers and inland wetlands. Significant reductions in amphibians’ range sizes are probable early impacts. In southern Africa, large lakes have shown increases in aquatic temperature, while the tropical cyclones that bring rain to the Maputaland Coastal Plain may move eastward, away from the African continent. Climate change is widely considered as a multiplier of other pressures on biodiversity, both exacerbating the effects of these pressures and altering the frequency, intensity and timing of events. Many of these shifts are predicted to benefit the survival of invasive species over native species and increase the outbreak potential and spread of disease. Considering that many freshwater species are range-restricted and that the fragmented state of ecosystems may prohibit range shift migrations, increasing the connectedness and size of the protected area network, including Ramsar sites, are key components of climate change adaptation strategies. In the inland aquatic realm, human responses to climate change are likely to further increase some pressures, for example, reduced rainfall due to climate change (exacerbated by biological invasions in catchment areas) drives an increase in water abstraction (for human settlements and agriculture), which compounds the pressure on the aquatic ecosystem and species.

Warming of as little as 1.5 °C poses a considerable threat to freshwater ecosystems and the many critical services these systems provide5, and 2 °C warming is highly likely to be exceeded in the middle of this century5,6. The winter rainfall region is at a higher risk of multi-year droughts, with the summer rainfall areas projected to experience similar risk should warming reach 1.5 °C or higher7.

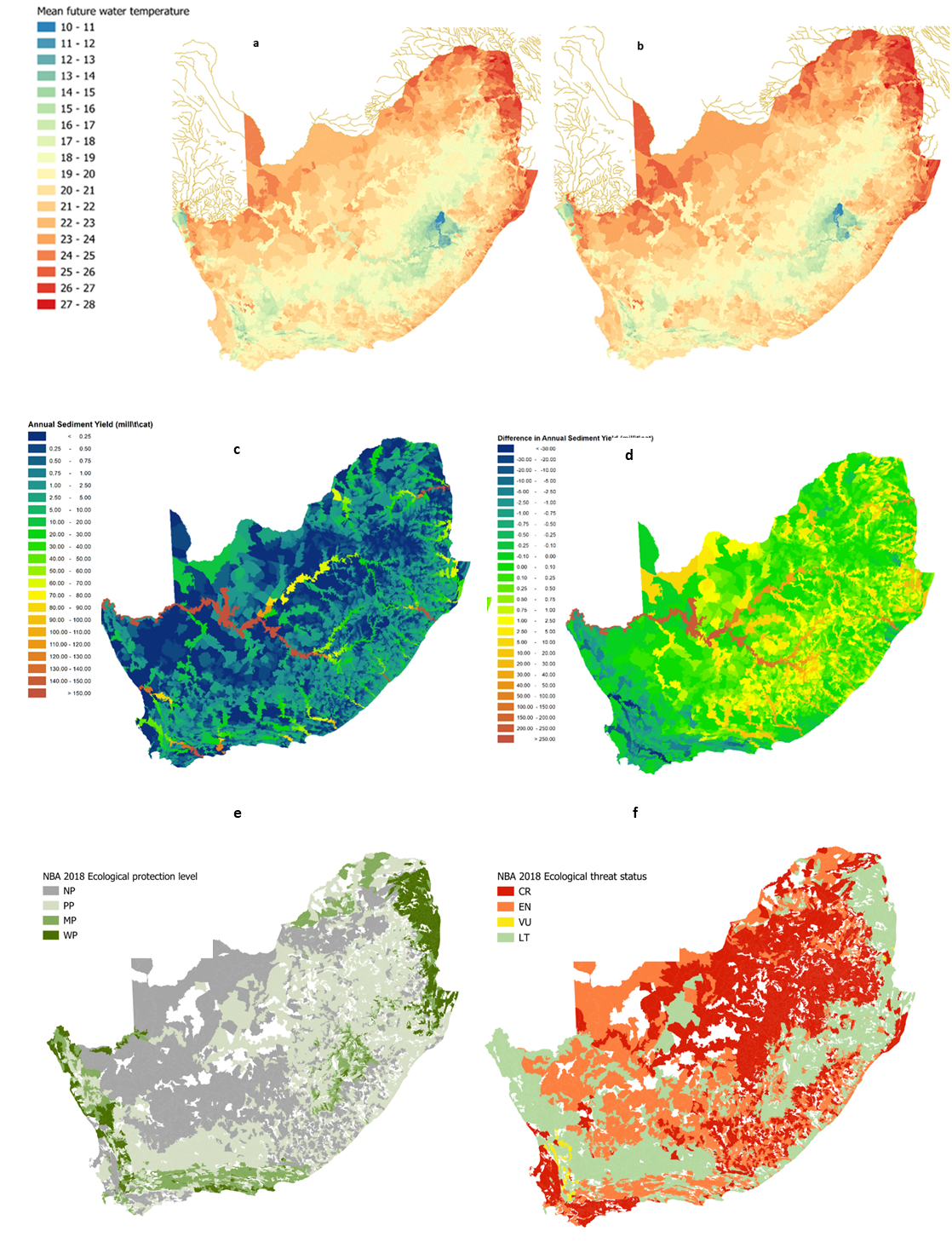

Impacts of climate change on water temperatures are projected to vary across South Africa by between 1 °C and 4 °C, with the highest increases in the semi-desert Kalahari. Areas of the already hot and dry Northern Cape are highlighted as being particularly imperilled by a situation of presently low protection level, high threat and climate-related pressures (Figure 1). The occurrence of certain types of land use within the surrounding catchment may raise water temperatures within rivers to around 0.1 °C higher than those driven by natural land cover. Notably, the Maputaland, coastal KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo areas, where temperatures can rise by 0.2 - 0.3 °C, are highlighted as particularly vulnerable given the combination of low protection status, high ecosystem threat level, and some of the largest predicted shifts in temperature. Highs of 0.6 to 0.7+ above natural water temperatures may occur where large urban areas are located (Figure 1a, b)8. Temperature shifts have potentially highly impactful effects on species close to their thermal thresholds, highlighting an urgent need to define sentinel species for South African freshwaters9.

Under climate change and current trends in land use, sediment accumulation is likely to shift. Shifts in climate may alter streamflows, affecting nutrient flows, geomorphic integrity and the hydrology of freshwater systems. Species and ecosystems dependent on predictable stream and nutrient flows may be put under increased pressure as a result of shifts in sedimentation. Projected climate change may result in higher sediment yields than at present conditions primarily in the centre and east of the country, and lower sediment yields along the west and south coastal areas, especially in wetter than average years (Figure 1c, d)8.

South Africa’s freshwater ecosystems are largely inadequately protected, and the NBA 2025 has identified those ecosystems that are both highly threatened and poorly protected. Many of these areas also overlap with areas where streamflow, water temperatures and sediment accumulation patterns are likely to undergo extensive change under near-future climate scenarios8. Knowledge of areas most affected by climate-related changes and that affect ecosystem functioning and vulnerable species (Figure 1e, f), is crucial to ensure effective and timeous management response.

Biological invasions

Biological invasions are a major pressure on the biodiversity and ecosystem functioning of all realms. A national report is released every three years – providing a comprehensive assessment on the Status of biological invasions and their management in South Africa. The report details alien species introduction pathways, their distribution and abundance, their impacts and the various interventions that have been put in place.

Alien invasive species cause substantial changes to ecosystem structure and function and negatively impact aquatic biota. Rivers and inland wetlands are the most heavily invaded ecosystems globally, largely due to their inherent connectivity and the intensity of anthropogenic activities. Of the 191 listed alien species in the freshwater realm, 65 are invasive. Of these invasive species, 27 severely impact biodiversity (5 fish species and 15 plant species). Nationally, 81% of freshwater fishes of conservation concern are impacted by invasive alien fishes. Many of these native species are endemic to the mountains of the Western Cape. The invasive species (e.g. bass (Micropterus spp.) impact on native species mainly through predation of juveniles and outcompeting adults for resources. This reduces population sizes and has caused population extirpation of many native species. In some cases, invasive species have hybridised with native species e.g. invasive Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and indigenous Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus). Invasive plants in rivers and wetlands threaten ecosystem integrity, alter fire regimes and change hydrological processes due to their high water consumption.

Technical documentation

Related publications and supporting information

Coming soon

Recommended citation

Job, N., Broom, C., & Kotze, D. 2025. Pressures on freshwater ecosystems: Freshwater (inland aquatic) realm. National Biodiversity Assessment 2025. South African National Biodiversity Institute. http://nba.sanbi.org.za/.

References

1. Zimmermann, D. et al. 2011. Avian poxvirus epizootic in a breeding population of lesser flamingos (phoenicopterus minor) at kamfers dam, kimberley, south africa.

Journal of Wildlife Diseases 47: 989–993.

https://doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-47.4.989

2. Hill, L. et al. 2013. Effects of water quality changes on phytoplankton and lesser flamingo phoeniconaias minor populations at kamfers dam, a saline wetland near kimberley, south africa.

African Journal of Aquatic Science 38: 287–294.

https://doi.org/10.2989/16085914.2013.833889

3. McCarthy, T.S. et al. 2007.

The collapse of Johannesburg’s Klip River wetland.

South African Journal of Science 103: 391–397.

4. McCarthy, T.S. & J.S. Venter. 2006. Increasing pollution levels on the witwatersrand recorded in the peat deposits of the klip river wetland : Research article.

South African Journal of Science 102: 27–34.

https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC96496

5. Capon, S.J. et al. 2021. Future of Freshwater Ecosystems in a 1.5°C Warmer World.

Frontiers in Environmental Science 9: 784642.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2021.784642

6. IPCC. 2023.

Climate Change 2022 Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed. Cambridge University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844

7. Scholes, R. & F. Engelbrecht. 2021. Climate impacts in southern africa during the 21st century. Global Change Institute, University of the Witwatersrand.

8. Schulze, R.E. et al. 2025. Development of a phased, updateable and multi-purpose, multi-space and multi-time hydrological modelling system to answer water related questions identified by SANBI. Centre for Water Resources Research, Pietermaritzburg.

9. Rivers-Moore, N.A. 2024. Temperature thresholds to guide choice of freshwater species for monitoring onset of chronic thermal stress impacts in rivers.

Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 79: 101–110.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0035919X.2024.2329920