Freshwater ecosystems are under severe pressure. These habitats are geographically constrained causing impacts to accumulate. Between NBA 2018 and 2024, freshwater fishes have remained among the most threatened vertebrate groups in South Africa. Waterbirds, dependent on freshwater habitats are declining, with several species becoming more threatened since 2015. Physical modification of rivers and wetlands, invasive alien species and climate change continue to accelerate declines.

of 655 taxa assessed are

Threatened

of 396 taxa assessed are

Well Protected

of 396 taxa assessed are

Not Protected

Threat status and pressures

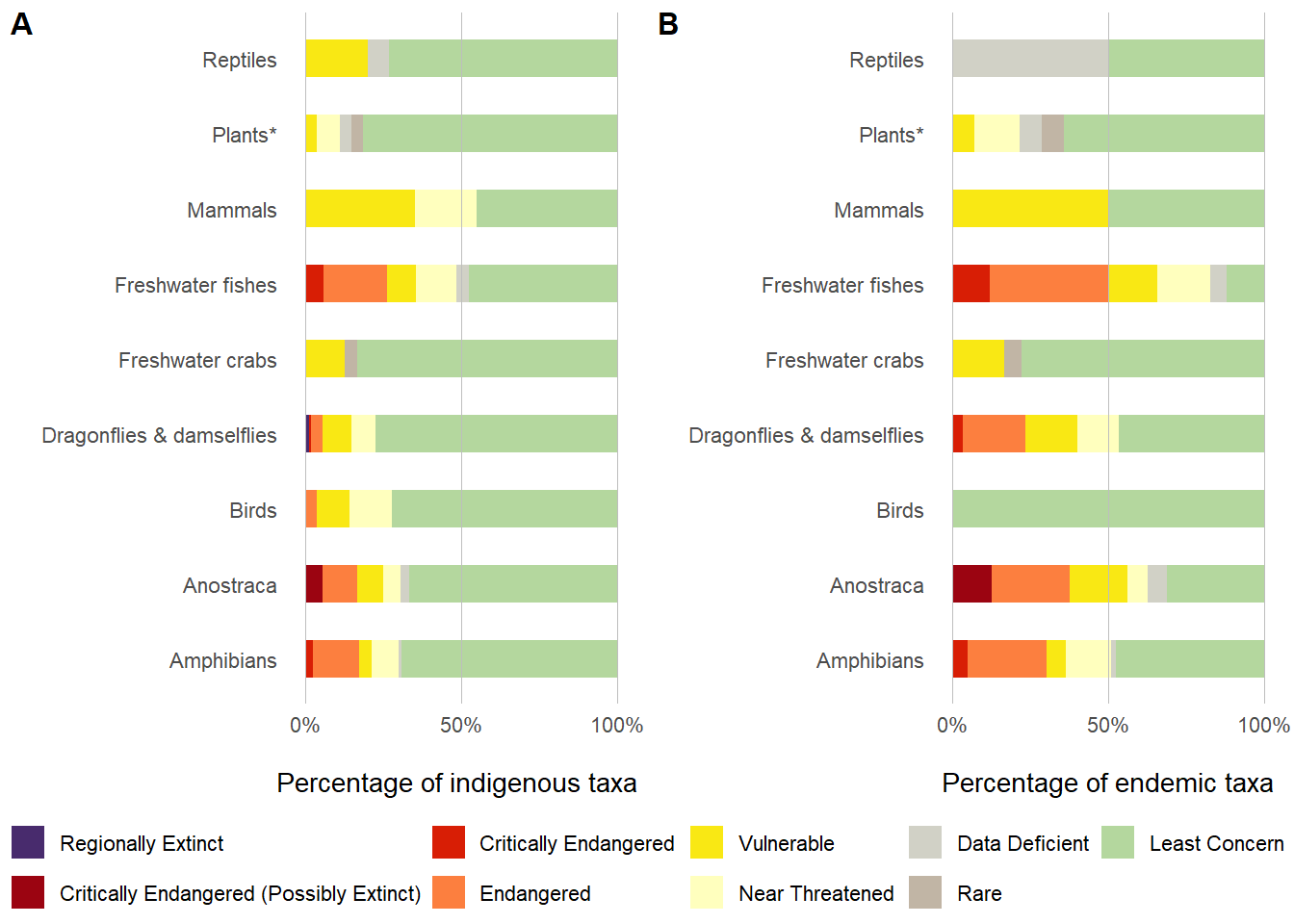

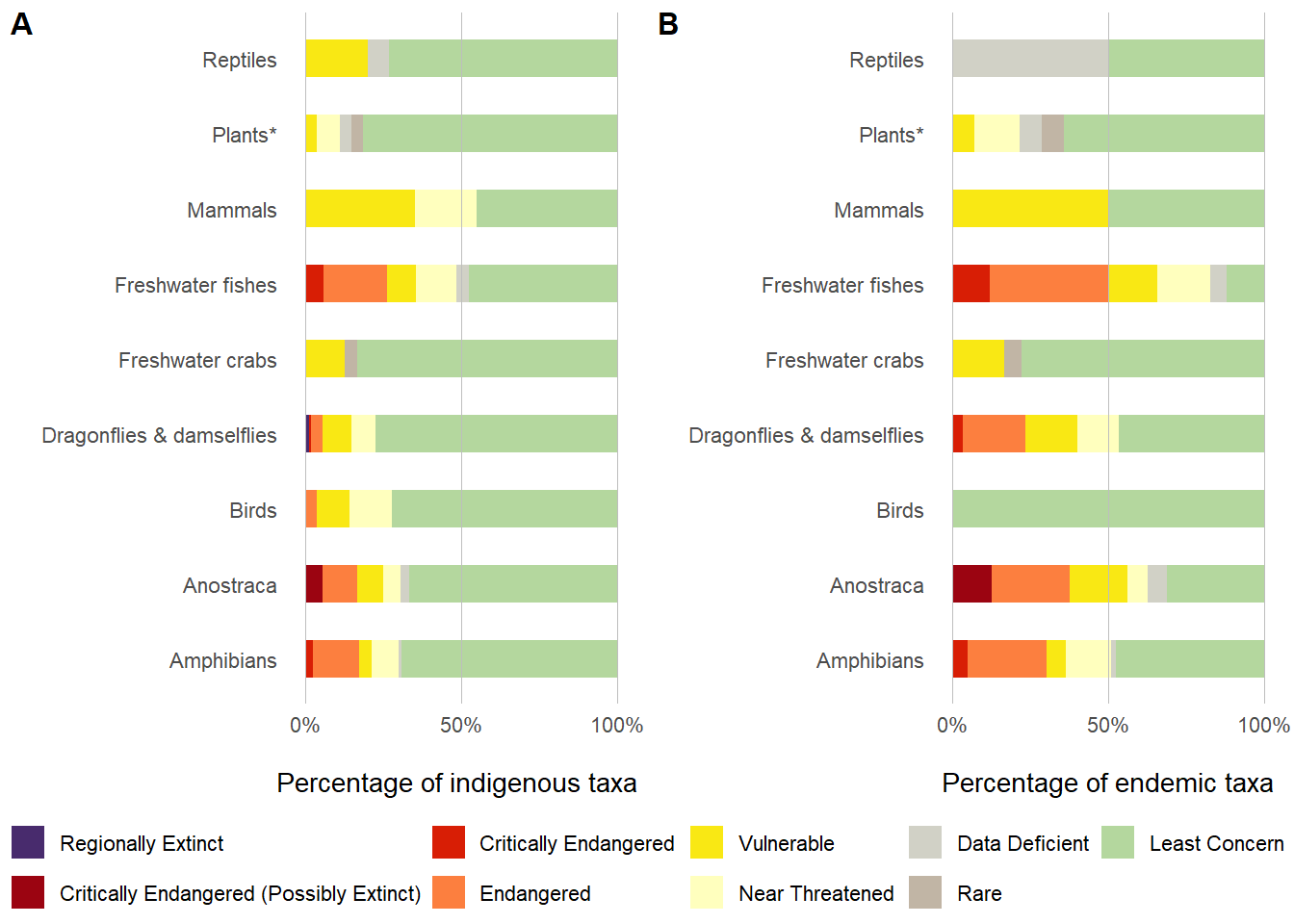

Using the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Categories and Criteria, 655 taxa that depend on freshwater habitats, including rivers and wetlands, were assessed to determine their risk of extinction (Figure 1, Table 1). To date, many freshwater-dependent taxa have not been included in IUCN Red List assessments due to the lack of comprehensive taxonomic understanding as well as limited distribution data. South Africa, as a mega-diverse country, is not likely to ever have the capacity to assess all known freshwater species, and hence groups included provide important insight into the conditions experienced by freshwater species.

Nine freshwater groups are included in this assessment, including, birds, mammals, amphibians, and reptiles (reassessed and completed within the last three years (2023 to 2025)), and for the first time, freshwater crabs and fairy shrimps (Anostraca), assessed in 2024 and 2025 respectively. Further, freshwater fishes and Odonata have not had their Red List assessments updated since the 2018 NBA, and here we present the findings of the 2018 assessments. These groups are due for reassessment in the next two years (2026-2027). Freshwater plants are represented by a small sample (27 from a 900-representative sample of all plants). A more comprehensive assessment of freshwater plants has been identified as a priority to be able to accurately report on their threat status in South Africa.

In general, most freshwater groups show high sensitivity to multiple pressures, the most serious being habitat loss and modification such as wetland drainage, pollution of river systems, agricultural and housing developments, over-abstraction of water, and the impacts of invasive alien species and climate change. Of all the assessed freshwater species, 20% (131 taxa) are classified as threatened (CR, CR(PE), EN and VU) with extinction, when accounting for other taxa of conservation concern (ToCC) (threatened species, DD, Rare and NT), these include 31% (206) of assessed taxa (see details on the Red List assessment process here. Further, 32% (201 taxa) of assessed taxa are endemic to South Africa, of which 42% (90 taxa) are threatened with extinction, meaning the responsibility to protect these species and prevent further losses rests solely with South Africa.

| Taxonomic grouping | Regionally Extinct | Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct) | Critically Endangered | Endangered | Vulnerable | Near Threatened | Data Deficient | Rare | Least Concern | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphibians | All indigenous | 0 | 0 | 3 | 17 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 81 | 117 |

| Endemic | 0 | 0 | 3 | 16 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 30 | 63 | |

| Anostraca | All indigenous | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 24 | 36 |

| Endemic | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 16 | |

| Birds | All indigenous | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 14 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 96 | 133 |

| Endemic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Dragonflies & damselflies | All indigenous | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 15 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 127 | 164 |

| Endemic | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 30 | |

| Freshwater crabs | All indigenous | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 24 |

| Endemic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 18 | |

| Freshwater fishes | All indigenous | 0 | 0 | 7 | 24 | 11 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 56 | 118 |

| Endemic | 0 | 0 | 7 | 22 | 9 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 58 | |

| Mammals | All indigenous | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 20 |

| Endemic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 8 | |

| Plants* | All indigenous | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 22 | 27 |

| Endemic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 14 | |

| Reptiles | All indigenous | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 15 |

| Endemic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

The following sections (and Figure 1 and Figure 2) give brief summaries of findings on freshwater species. For a full reflection on each taxonomic group, follow links on the headings.

Fairy shrimps

South African fairy shrimps (Anostraca) species represent habitat specialists that occupy temporary freshwater habitats.In 2023, the first comprehensive assessment of South African Anostraca was initiated through the NRF FBIP REFRESH Project. This contributes 58% of the global Anostraca IUCN assessments, making a sizeable contribution to the understanding of the current state of these temporary freshwater habitat indicator species. Of the 36 species assessed, 25% (9 species) were found to be threatened with extinction (Figure 1 and Table 1). The main driver of threat was habitat loss and degradation due to urban expansion and agricultural activities. These species’ habitats are varied and include endorheic (internally drained) wetlands, remnant riverine pools, rock pools, roadside ditches, and even animal wallows. These habitats are not permanent features in the landscape and hence are impacted by activities when they are not inundated. An increase in awareness is needed to protect these highly diverse and dynamic habitats. In recent years, there has been some interest in sampling and identifying these species using both morphology and genetic tools. This has led to the discovery of new species1, as well as range extensions.

Freshwater fishes

South Africa’s freshwater fishes are the second most threatened comprehensively assessed taxonomic group (see ecosystem threat status), with 36% (42 taxa) assessed as threatened, and when only considering endemics, 66% (38) are threatened (Figure 1 and Table 1). Freshwater fish have not been reassessed since 2018, but field observations and the status of South African rivers and wetlands indicate that pressures have not ceased and continue to mount (see freshwater ecosystem condition). A breakthrough for this group since the last assessment in 2018 has been an immense investment in the expansion of the taxonomic understanding of many freshwater fishes, through resolving species complexes and describing new species (see Box 1). These taxonomic advances are critical to enable Red List assessment updates. Along with taxonomic updates of many species, a large number of field surveys have improved our understanding of active threats and the condition of the habitats of many fishes.

Major pressures that have persisted for freshwater fishes and their habitat are competition with invasive alien fish and degradation of their freshwater habitat through water abstraction, pollution, and inappropriate sedimentation. Many emerging pressures have been identified through recent surveys, but their impacts on freshwater fishes will be interpreted and accounted for within the next update of the Red List of South African freshwater fishes. Of particular concern is illegal mining activity in the north-eastern regions of the country within river systems hosting highly threatened and restricted fishes (e.g. Enteromius treurensis) see Box 2.

The current list of freshwater fishes excludes migratory fishes such as the eel species present in South African freshwater and marine realms, thus representing a knowledge gap. Further work is required to enable comprehensive reporting on the state of migratory fish species.

Birds

There are 166 birds associated with freshwater ecosystems (waterbirds), and of these, 133 have been assessed using the IUCN Regional Red List. Of these waterbirds, 14% (19 species) of the species are threatened with extinction and 28% (37 species) are taxa of conservation concern (TOCC) (threatened species, DD, Rare and NT) (Figure 1 and Table 1). Since the 2015 Red List assessment, there has been a sharp decline in the status of many waterbird species, with many species recently being uplisted from Least Concern to an IUCN threat category (see Box 3). Of the thirty-nine bird species that have been uplisted to a higher threat category, nineteen are waterbirds (48% of uplisted birds are water birds).

An few examples is the African darter (Anhinga rufa) which has experienced a significant decline in its habitat availability through habitat loss (e.g. wetland drainage), impacts on breeding sites and environmental pollution (e.g. pesticide use and run-off, effluent). The maccoa duck (Oxyura maccoa), has been uplisted from Near Threatened to Vulnerable, due to the impacts of invasive alien species (e.g., water hyacinth, Eichhornia crassipes, in its wetland habitats. The half-collared kingfisher (VU) (Alcedo semitorquata) provides an example of a habitat specialist dependent on fast-flowing, clear, perennial streams and rivers that offer sheltered conditions and dense marginal vegetation. These types of habitats are increasingly threatened by pollution, siltation, and reduced flow due to over-abstraction of water and prolonged drought.

Besides habitat loss, many of these waterbirds are congregatory in nature, which makes them vulnerable to disease outbreaks. Waterbirds merit increased protection at key protected areas to prevent accelerated rates of decline. Urban freshwater habitats present unique opportunities for citizen-led habitat restoration and monitoring.

Reptiles

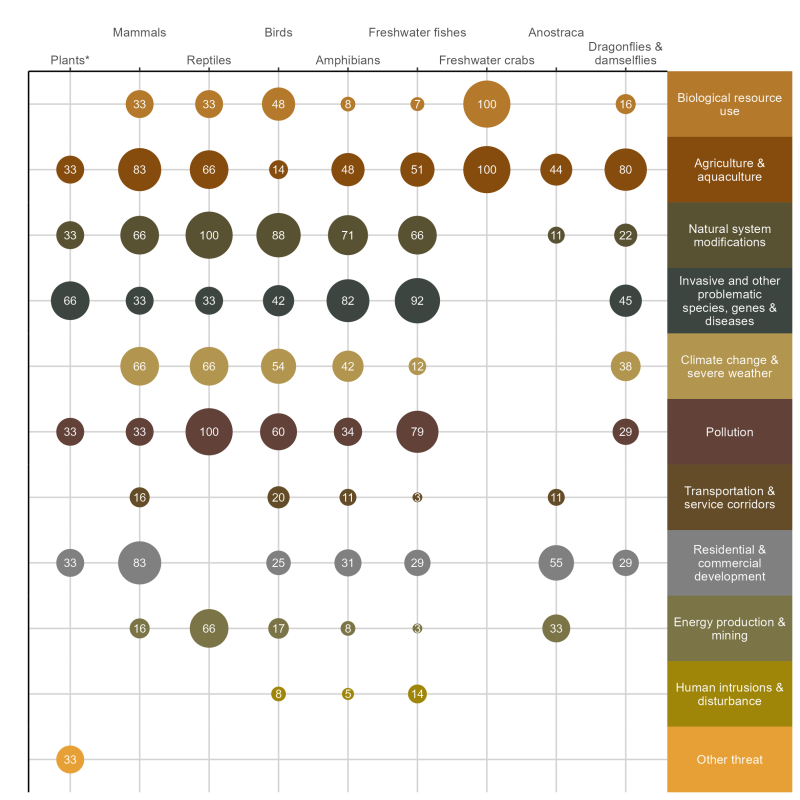

Of the 407 reptile species indigenous to South Africa, 15 species are dependent on freshwater habitats. Four of the 15 species (20%) are taxa of conservation concern (ToCC), three of these are assessed as Vulnerable, and one is assessed as Data Deficient (Figure 1 and Table 1). The major pressures on these ToCC are natural system modification and pollution, which are impacting all threatened species, followed by 66% of ToCC impacted by agricultural and mining activities, causing habitat degradation (Figure 3). Climate change and its associated effects on weather patterns and temperature have been identified as a current or potential future threat to some threatened reptile species. However, more monitoring is required to fully understand these impacts in South Africa. Increase in intensity of fires and a change in the timing of seasonal burns may affect these species during their hibernation period. While no freshwater-associated species have experienced a change in their IUCN Red List status, resulting in the RLI remaining stable, there has still been a continuation and exacerbation of pressures within these species’ habitats.

See the Conservation assessment of South African reptiles for more details.

Amphibians

A total of 135 amphibian species occur in South Africa. Of these, 117 species are dependent on freshwater ecosystems for survival and successful reproduction. Twenty-one percent of the 117 taxa (25 taxa) are threatened with extinction, and an additional 9% (11 taxa) are ToCC (1 Data Deficient and 10 Near Threatened). Almost 50% (63 taxa) of freshwater-dependent amphibians are endemic to South Africa, of which 36% (23 taxa) are threatened with extinction and 16% (10 taxa) are additional ToCC (Figure 1 and Table 1). The most important pressure driving species threat status for amphibians is the impacts of invasive alien species, including infectious diseases and invasive alien trees. Invasive alien trees impact water storage reservoirs and interrupt stream-flow consistency.

Amphibians have shown a genuine change in Red List status between the assessment period 2017 to 2025 for only two species, and one of these is dependent on freshwater habitats (Figure 2). Phofung river frog (Amietia hymenopus) restricted to the high altitude areas of the Drakensberg in Lesotho and northern KwaZulu-Natal, has been uplisted from Near Threatened to Vulnerable, due to deterioration in habitat quality, especially in Lesotho and areas bordering South Africa, where mines and proposed mines have had an observable increase in impact (both directly and indirectly) on this species. The species is also projected to be impacted by increased aridification across its range due to climate change, and overgrazing and water quality issues that have intensified since the last assessment. Recognized as a major global threat, climate change is increasingly driving amphibian declines in South Africa, affecting nearly half of threatened species, though its impacts remain hard to measure (Figure 3).

Mammals

At least 336 mammal species occur in South Africa, and their IUCN Red List status was assessed in 2025. At least 21 of the 336 taxa assessed make extensive use and are dependent on freshwater habitats. Of these 21 species, 33% (7 taxa) are threatened and 19% (4 taxa) Near Threatened (Figure 1 and Table 1). Only eight species are endemic and four of these are Vulnerable. Since 2004, the RLI has declined sharply for freshwater mammals, with this downward trend continuing from 2015 into 2025. In contrast, terrestrial mammals have experienced a much slower rate of decline over the same period see terrestrial species summary. Of the 21 taxa dependent on freshwater systems, two species, the laminate vlei rat (Otomys laminatus) and the Cape shaggy rat (Dasymys capensis) have increased in their threat status, largely due to a reduction in wetland habitat, causing species population reduction (Figure 2). There has been no improvements in species status, as has been observed for mammals in the terrestrial realm. This supports the call for more conservation efforts focused on restoring and maintaining river and wetland habitats.

Plants

Aquatic (freshwater) plant species were not reassessed for the NBA 2025 , and only a small sample of 27 species is included in the freshwater summary statistics that have been extracted from the 900 representative sample of plant species for South Africa (Figure 1, Table 1). For a more detailed analysis of the status of freshwater plants, see NBA 2019 Freshwater technical report4.

Invasion of wetlands by alien plants is the most important pressure to aquatic plants based on both the current analysis as well as the previous analysis using a sample of aquatic plant species (Figure 4). Of the 27 plants classified as aquatic in the current assessment, 66% of ToCC are directly impacted due to competition for space and resources from invasive alien species.

Dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata)

Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies) species are excellent indicators of freshwater habitat condition and serve as umbrella species for other aquatic macro-invertebrates5. There are 162 species known to occur in South Africa, with a fifth of these species endemic to the country (Figure 1 and Table 1). This group has been assessed multiple times globally and nationally and was included in the NBA for the first time in 2018 and the results presented here are from that assessment4, as the group has not been updated since.

Most of the Odonata species have been assessed as Least Concern (79%), as they have wide distribution ranges. They have also shown little change in their Red List status over the previous assessment period, as measured using the RLI (Figure 2). Some taxa are range restricted, and 33 taxa (20%) are ToCC (Figure 1 and Table 1). The main pressure faced by dragonflies is the shading out of their habitat (affecting 15 taxa) by invasive alien trees; they are also threatened by habitat modification due to livestock farming (affecting 14 taxa) and non-timber crop cultivation (affecting 11 taxa) (Figure 3). Some reprieve for the 15 taxa facing impact from invasive alien trees has come from highly effective invasive tree eradication programmes, with some remarkable success stories of re-colonization of habitats following the removal of these trees. Two species (Chlorocypha consueta and Crenigomphus cornutus) that were assessed as Critically Endangered Possibly Extinct in 2008 were re-assessed in 2017 as Regionally Extinct (RE). Despite extensive searches, these species have not been recorded since their initial discovery in South Africa in the 1950s and 1960s, respectively. An update on the state of Odonata will be provided in the next assessment due in 2027.

Freshwater crabs

Freshwater crabs, represented by two genera in South Africa, Potamonuates (23 taxa) and Maritimonautes (1 species), have been included in the NBA for the first time to improve representation of freshwater invertebrates. This group was first assessed in 2008 as part of the regional southern African freshwater IUCN Red List assessment6. Since 2008, there has been a proliferation of species descriptions. This group now consists of 29 described species, including five newly recognized species that have been described since 20238. The most recent assessment was concluded in 2023 and included 24 freshwater crab species that were described pre-2023. Freshwater crabs, unlike other freshwater dependent groups, seem to be less impacted by modified systems, and based on the IUCN Red List assessments, only 3 of the 24 species are assessed as threatened (12% - are Vulnerable), and one species is assessed as Rare. These three species are highly restricted and recently described — Potamonautes ntendekaensis (VU) , Potamonautes ngoyensis (VU), and Potamonautes mhlophe (VU). It is suspected that they might have a wider distribution; however, based on current knowledge of their distributions, they have been listed as Vulnerable. Their habitats, mostly fragmented forests, are impacted by habitat disturbance due to impacts on the forest margin and trampling by livestock .

Apart from these species, most freshwater crabs have been assessed as Least Concern (83%, 20 species) and found to be highly resilient and have persisted in modified river systems and impacted wetlands. There is, however, no monitoring of this group, and long-term trends are not currently available. Monitoring is needed to confirm whether these species have high tolerance for changing and impacted habitats or whether there is a lack of detection of impacts. At present, freshwater crabs and Odonata are the only freshwater groups with low proportions of threatened species. Interestingly, both groups can utilise terrestrial systems if needed, likely increasing their tolerance to disturbances within the freshwater system.

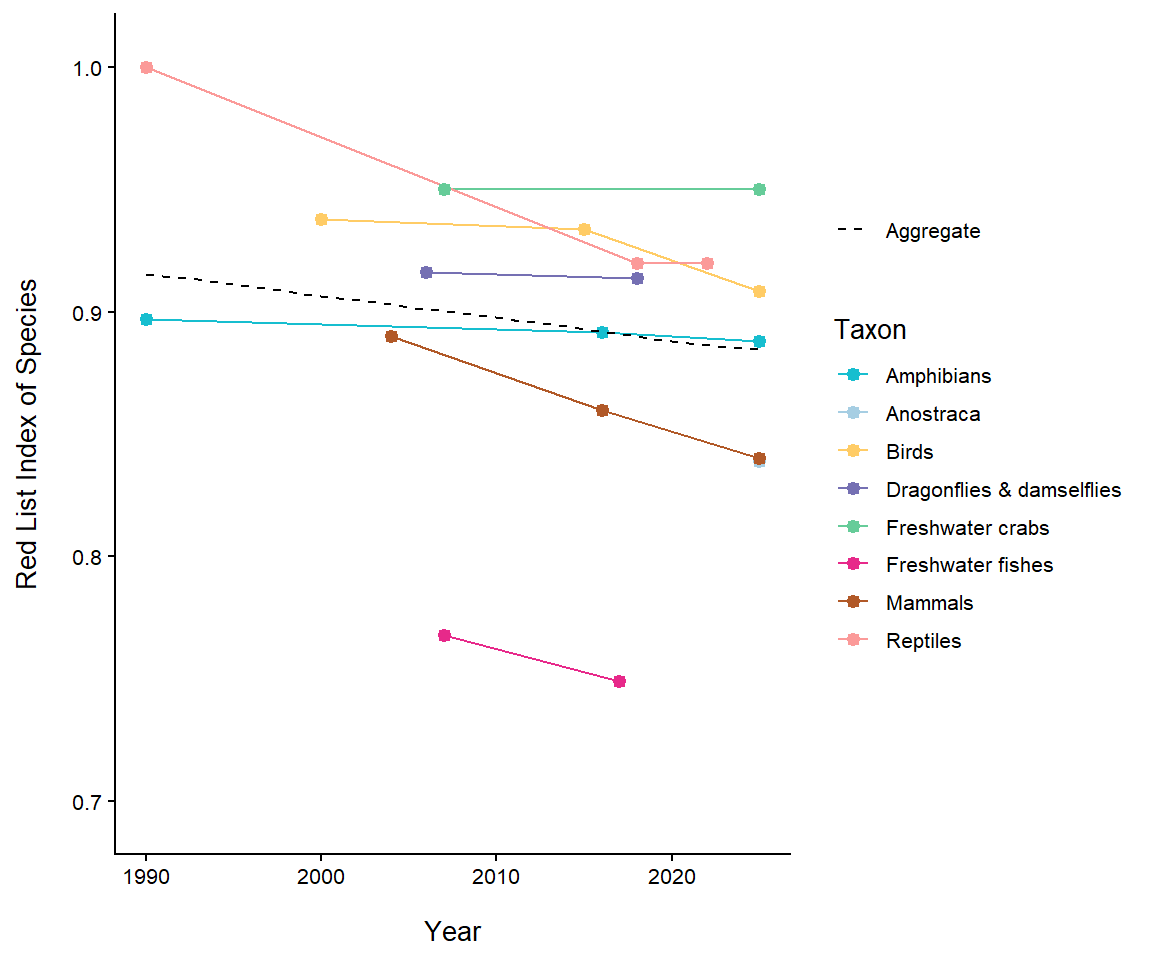

Trends - the Red List Index

The trend in freshwater species status over time was measured using the globally recognized indicator, the IUCN Red List Index of species (RLIs)9. The RLI is calculated for each taxonomic group based on genuine changes in taxa assignments to Red List categories over time. The RLIs value ranges from 0 to 1, where the lower the value the faster the taxonomic group is heading towards extinction – i.e. if the value is 1, all taxa are Least Concern and if the value is 0, all taxa are assessed as Extinct.

The taxonomic group at highest risk of extinction is the freshwater fishes. Steep declines were recorded between 2007 and 2016. While only due for reassessment in 2026, the declining status of rivers and dwindling resources available for management actions where many of these species are concentrated (Western Cape, Eastern Cape, and KwaZulu-Natal) likely means that they will continue on a declining trajectory. Anostraca currently only has a single RLI point and it is below the national average, just second to freshwater fishes, and just below freshwater mammals. This indicates that this group has a high proportion of species that are assessed as threatened. Of the 20 freshwater-associated mammals that occur in South Africa, two have become more threatened since their last assessment in 2016. Amphibians and reptiles have had no changes in the status of species between the assessment period, possibly indicating some stabilisation; however, based on their recent assessments, many species are experiencing continued pressures, but not to the point of triggering an uplisting. Between the two assessment periods for Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies), this group had four deteriorations in status – species becoming more threatened due to habitat loss and degradation, and two improvements due to effective invasive alien plant species control4. The improvements and declines in threat status balance out and the group’s RLI score is above the national average for freshwater species (Figure 2).

After freshwater fishes, in the most recent assessment period, freshwater birds (water birds) have the steepest negative trend. Nineteen birds have been uplisted due to a genuine increase in their risk of extinction, and two species have been downlisted —wattled crane (Grus carunculata) and the southern bald ibis (Geronticus calvus). The major drivers for increased threat are linked to climate change, through prolonged drought and shifts in rainfall and temperature regimes (see box 4). Focussed conservation efforts have resulted in improvements for these two species. Freshwater crabs have been assessed twice and are included here for the first time. This group has remained stable, due to their ability to persist in modified habitats. Freshwater plants are excluded from this trend analysis, as a sufficiently large representative sample is not currently available.

Protection Level

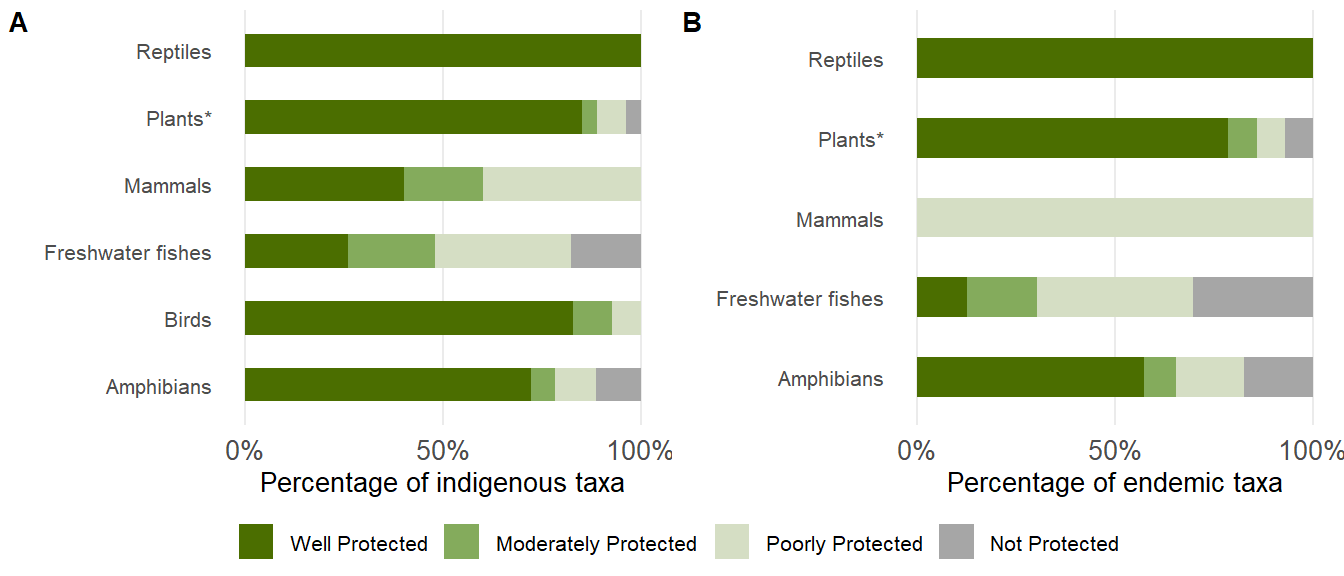

The 2018 NBA assessment4 found that most freshwater species were relatively well protected with the exception of freshwater fishes which were Poorly Protected. The current analysis shows the same pattern. Because freshwater systems are linear and many threats, such as pollution, invasive species, and water abstraction, originate upstream and outside protected areas, these pressures cannot be effectively mitigated within protected area boundaries. Protected areas are also mainly managed for terrestrial biodiversity, further limiting freshwater species protection.

Only 26% of freshwater fish taxa included in the analysis were Well Protected (25 taxa), while the majority (74%, 71 taxa) are under protected, including Not Protected (17 taxa), Poorly Protected (33 taxa), or Moderately Protected (21 taxa) (Figure 4). Seven freshwater fish are assessed as Critically Endangered and four of these taxa are also assessed as Not Protected. These four are the Treur River barb (Enteromius treurensis), Barrydale redfin (Pseudobarbus burchelli), Pseudobarbus senticeps and Galaxias sp nov ‘slender’, all with very restricted distributions - some limited to a single stretch of a river or a single sub-quaternary catchment. This finding has not changed since 2018 and this group remains highly threatened and under-protected. Thirty-three taxa are listed as Poorly Protected, these occur across South Africa, with the majority of the taxa assessed as threatened or Near Threatened (25 taxa).

Other taxonomic groups included in this analysis contrast strongly with freshwater fish, as the majority of species are Well Protected (Figure 4). However, when assessing under-protected species, these include 32 amphibians 18 birds, and 11 mammals. These under-protected species include a number of threatened and Near Threatened species for birds (4 taxa), amphibians (20 taxa), and mammals (7 taxa). Interestingly, all freshwater-dependent reptiles are assessed as Well Protected. Of the four birds assessed as under-protected, the white-winged flufftail (Sarothrura ayresi) (EN) was previously assessed as Not Protected (2017) and has now been assessed as Poorly Protected (2025)11. See White-winged flufftail project for further details.

Of the eleven amphibian species assessed as Not Protected, nine are assessed as threatened. The rough moss frog (Arthroleptella rugosa) (CR) and the Amatole toad (Vandijkophrynus amatolicus) (EN), remain Not Protected, since its initial assessment in 2017. Many newly described species, have been assessed as Not Protected, as their current known distribution does not overlap with protected areas (see the amphibian page for more details). In the case of mammals, four species are assessed as Poorly Protected. Interestingly, the spotted-necked otter (Hydrictis maculicollis – VU) and the southern reedbuck (Redunca arundinum – LC) have widespread distributions within South Africa, but limited overlap with the protected area network. This reflects the terrestrial bias of the current protected area network, which was not designed to protect rivers. Protected area expansion needs to address this bias.

Recent expansion of the protected area network has improved protection for some species, but many threatened freshwater species—especially freshwater fish—remain under-protected. Improving management within existing protected areas could greatly strengthen conservation outcomes. While protected areas help buffer species from land-use change, stronger management is often needed to meet conservation goals. For freshwater systems in particular, effective conservation requires protection and coordinated management at the whole catchment level, not just within individual protected areas. Further details will be provided in the technical report.

Conservation efforts

The Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) Target 4 is a critical commitment, requiring signatories to halt human-induced extinctions and improve species’ conservation status by 2030. Achieving this ambitious goal necessitates coordinated efforts among nations to effectively reverse species declines and maintain genetic diversity, particularly within populations of threatened species. South Africa contributes to Target 4, engaging with each taxonomic group and prioritising species for urgent recovery through comprehensive taxonomic Red List assessments. South Africa has initiated a process with each taxonomic group that has comprehensive Red List assessments for their taxonomic groups, to identify and prioritise species in urgent need of recovery to contribute to achieving the GBF Target 4 goals (see freshwater fish recovery efforts).

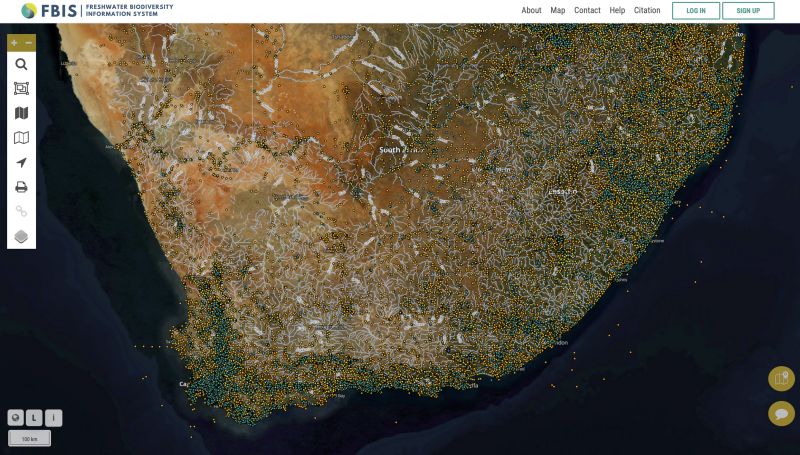

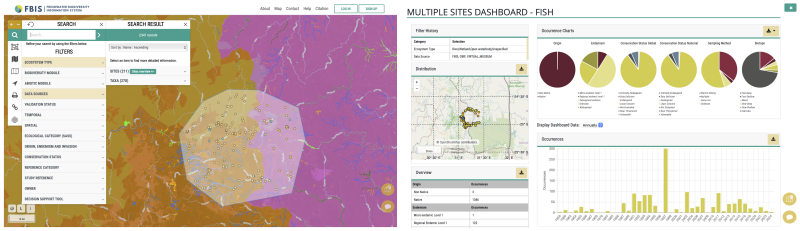

Addressing and improving freshwater health will take considerable political will and resources. Many national, provincial and local initiatives are underway to improve the conservation of freshwater species (see freshwater fish recovery page). Several conservation and planning tools have been developed including the National Freshwater Ecosystem Priority Areas (NFEPA) project and the DFFE Environmental Screening Tool, as well as the Freshwater Biodiversity Information System (FBIS), developed and led by the Freshwater Research Center (see box on FBIS). These tools can be used to reduce impacts on freshwater ecosystems and species, and guide decision-making. NFEPA is currently being updated, and will be an important strategic spatial plan to integrate and strengthen freshwater ecosystem and species-related planning and decision-making across government and civil society.

Monitoring

Protecting and managing freshwater habitat is vital for securing water resources and the many remaining undocumented or undescribed freshwater species. Although the 2018 National Biodiversity Assessment (NBA) showed clear fish decline, the true freshwater ecosystem and species crisis was likely underestimated due to insufficient data on freshwater-specific groups. The current assessment has improved this by including fairy shrimps (Anostraca) and freshwater crabs. Anostraca data now clearly reveals severe impacts in ephemeral habitats, contrasting with the relatively less threatened status of the more mobile freshwater crabs.

• In the coming years, there will be a focus on including freshwater Mollusca to expand the freshwater-dependent taxa

• Further, the proposed updating of NFEPA to include other freshwater taxonomic groups will ensure freshwater priority areas are identified that support critical species conservation.

• The expansion and strengthening of the River Eco-status Monitoring Programme (REMP) is essential; this can be achieved through coordination and collaboration between all partners from the national government, provincial agencies, NGO’s and researchers. Due to a range of constraints, for example, funding limitations, the activities of the REMP have not been as efficient and effective as they could be.

• Monitoring of freshwater species is undertaken at the provincial level, yet many conservation agencies have few remaining freshwater ecologists and technicians. In the 2018 inland aquatic NBA technical report12 a key message was that there was a noticeable decline in skilled staff and budget assigned to monitoring and interventions in freshwater systems. Observations and engagements with expert partners for this NBA suggest that this trend has continued, and there is a need to quantify the loss in capacity and to assess the drivers of this loss in capacity, to make sure that monitoring efforts are resumed to serve as early warnings and to inform planning and decision-making.

Approach

Threat status assessment

See this page for details about threat status assessments for species.

In the 2025 assessment of freshwater species, there has been a concerted effort to present a more balanced representation of freshwater species and to include more freshwater invertebrates. Nine freshwater groups are included in this assessment, including, for the first time, freshwater crabs and Anostraca species. This addresses a gap identified in the previous NBA13, where only Odonata represented freshwater invertebrates.

Noting, that freshwater plants, only a small sample is presented (27 from a 900-representative sample of all plants). A more comprehensive assessment of aquatic plants has been identified as a priority to be able to accurately report on their threat status in South Africa. Further,

Assessment limitation and improvements needed for freshwater species: The current list of freshwater fishes excludes migratory fishes such as the eel species present in South African freshwater and marine realms, thus representing a knowledge gap. Further work is required to enable comprehensive reporting on the state of migratory fish species.

Protection level assessment

The species protection level assessment measures how effectively South Africa’s protected area network safeguards a species. It evaluates progress towards achieving a persistence target for each species – the level of protection needed to support long-term population survival. Because persistence depends on the area protected and on the ability of protected areas to reduce pressures that drive population decline, a protected area effectiveness factor is included in the calculation.

This assessment was applied to 268 mammal species with the persistence targets set either at the area required to protect 10 000 individuals or at a minimum viable population with standardised MVP estimates obtained from meta-analyses14.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the many individuals, and specificially, the freshwater taxon experts, who gave up their time to participate in workshops, discussions, and authored and reviewed individual species assessments. BirdLife South Africa who led the regional assessment of South African birds across realms. The Endangered Wildlife Trust is thanked for their leadership of the assessment of South African mammals and amphibians (supported by Anura Africa) across realms. We acknowledge the SANBI and SAIAB led NRF FBIP REFRESH project for supporting red listing of Anostraca. All provincial agencies that have provided data or insights into effectiveness of protected areas across South Africa. We are most humbled by all the members of the IUCN South African Species Specialist Group for their contributions and participation in discussions for species assessments.

Coordinated by:

Supported by:

Freshwater taxon experts

Provincial agencies – data, insights on protected area effectiveness

IUCN South African Species Specialist Group members

Contributors

| Contributor | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Anisha Dayaram | South African National Biodiversity Institute |

| Carol Poole | South African National Biodiversity Institute |

Recommended citation

Van Der Colff, D., Raimondo, D.C., Job, N., Broom, C.J., Roux, F., Shelton, J., Milne, B., Dallas, H., Daniels, S., Liddle, N., Jordaan, M., Lee, A., Chakona, A., Hendricks, S.E., & Monyeki, M.S. 2026. Species status: Freshwater realm. National Biodiversity Assessment 2025. South African National Biodiversity Institute. http://nba.sanbi.org.za/.

The NRF Foundational Biodiversity Information Programme (FBIP)

The NRF Foundational Biodiversity Information Programme (FBIP)