Illegal harvesting and trade of South Africa’s species is increasing, with conventional law enforcement and legislative approaches failing to prevent population decline and near extinction of several species (established). Interventions that increase revenue within the conservation sector and contribute meaningfully to local livelihoods are required.

TRAFFIC.png)

South Africa’s rich biodiversity, combined with socio-economic challenges, has led to increasing illegal trade of numerous high value species in all realms. Around 9 500 southern white rhinoceroses (Ceratotherium simum simum; Near Threatened) were poached between 2010 and 2023. Tens of thousands of plants of South Africa’s 37 cycad species (Encephalartos spp.), 71% of which are threatened, have been illegally harvested from wild populations in the last three decades – even from protected areas. A lack of effective guardianship of Endangered South African abalone (Haliotis midae) has seen an estimated 90% reduction in abundance over the past 35 years. The West Coast rock lobster (Jasus lalandii) has changed from Least Concern to Endangered largely because of illegal fishing. Official seizures and analyses of online trade show that reptiles, medicinal plants, seahorses, pipefish, sea cucumbers, marine gastropods (cowries, cone-shells, etc.), fish maw (swim bladders) and live ornamental aquarium species (including sharks, rays and corals), are being targeted. Some illegal harvesting methods (e.g., the use of gill nets for illegal fishing) are indiscriminate, affecting non-target species as well.

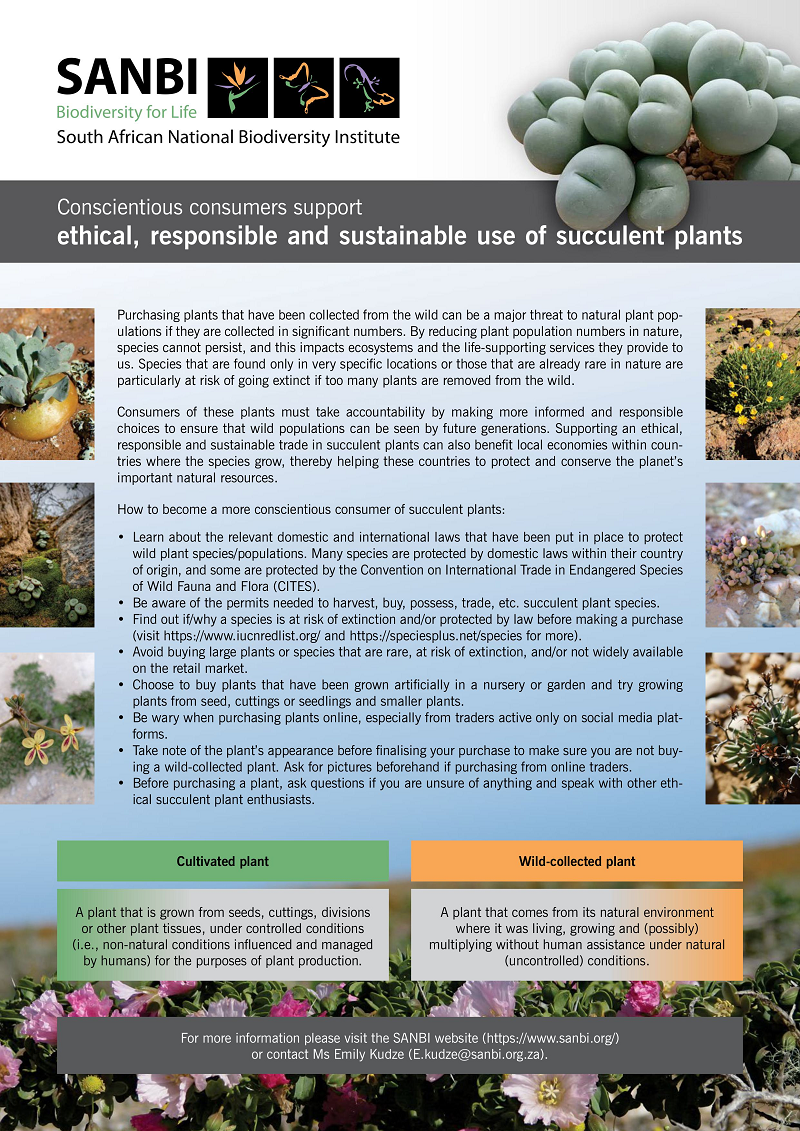

Since 2020, illegal harvesting of ornamental succulent and geophytic plants, in high demand in Europe and Asia, has seen a dramatic escalation in the Succulent Karoo Biome where range-restricted endemic plant species are easily accessible and local people have limited livelihood opportunities. Over 1.1 million harvested plants have been confiscated, 632 species populations are in decline, and the populations of 12 endemic species have been reduced to functional extinction1.

Addressing illegal wildlife trade through conventional law enforcement, focussed on stringent legislative measures such as trade prohibitions, is failing. For example, despite substantial enforcement, policy and management efforts directed towards curbing the poaching of rhinos, many have been killed within state-owned protected areas, leaving the private sector with the responsibility of protecting just over half the national herd. Similarly, 96 million South African abalone have been poached in 10 years, despite a severely reduced catch limit for the legal fishery. Many of the comprehensive response strategies and management plans, particularly for cycads and succulents, are severely under-resourced and poorly implemented, while conservation agencies lack resources for effective compliance measures.

Contributing to a sustainable biodiversity economy through legal trade offers a new frontier for addressing wildlife crime by supplying persistent demand whilst directly tackling socio-economic challenges and generating funds for conservation. Molecular techniques, such as DNA and stable isotope forensics, as well as the use of artificial intelligence, 3D printing and other accessible digital technologies that improve monitoring, training and databasing, provide innovative technological solutions for ensuring that trade is well-regulated and does not threaten wild populations.

Notes

Functional extinction means that there are too few individuals left in the wild for the population to be viable and recover from the impacts of illegal collection.↩︎